Steve VanderVeen: John Fenlon Donnelly and the development of automobile mirrors

John Fenlon Donnelly experienced the best, worst, and best of business times.

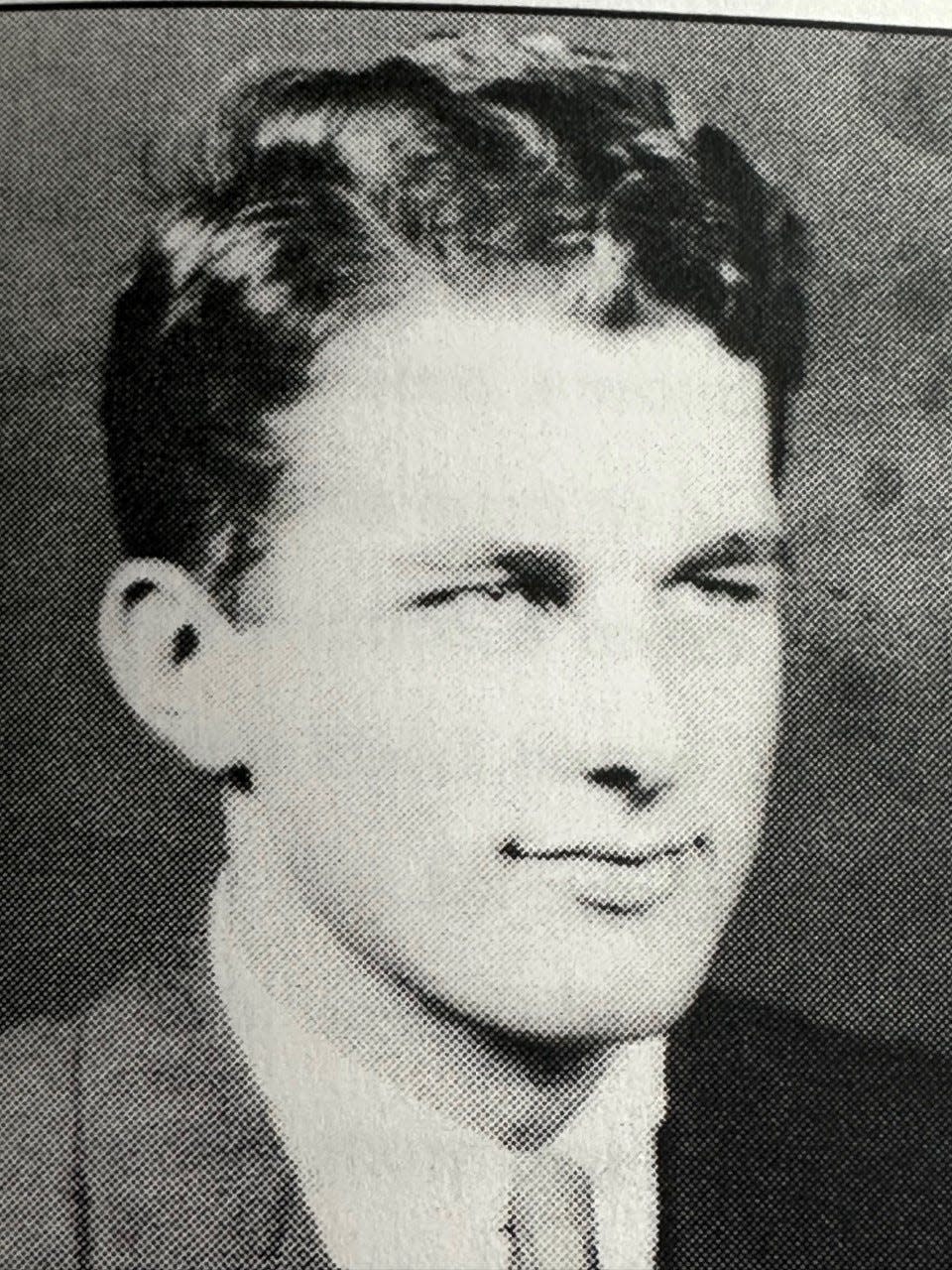

He was born in 1912, the fourth of five children, to Bernard and Mary Catherine Fenlon Donnelly in Holland, Michigan. As a child, he watched skilled workers at his father’s business, the Donnelly-Kelley Glass Company, grind, polish and engrave glass for decorative mirrors and sell them to West Michigan furniture companies.

In 1924, Bernard bought Kelley’s share of Donnelly-Kelley. Then, as the automobile industry accelerated, John watched his father launch a new company, Duffy Manufacturing, to produce windows encased in wooden frames for automobiles with cloth tops, or “touring” cars.

More:Bernard Donnelly shared everything with his neighbors but his religion

In the late 1920s, John continued to learn from his father, even after he left home to study at Notre Dame. When he arrived in South Bend, he received the following advice: "One good plan to adopt and insist upon yourself is to complete each day's work each day — never put it off [until] the following day. If you put things off, the chances are that you will never do [them] and, as a result, your foundation will have many holes in it.”

Later, Bernard wrote: "Are you still going to mass every morning, and do you still go to Holy Communion?" He also repeated his previous message: "Are you keeping up your daily work and doing every day the thing that should be done that day? When you are tired, do it anyway."

In 1931, John decided to leave Notre Dame, where he was pursuing an engineering degree, for Catholic University in Washington, D.C. He studied philosophy and the liberal arts, possibly because he was considering priesthood. Meanwhile, Holland Furnace Company was courting Bernard to be on its board.

But two things interrupted their efforts: Bernard’s premature death on December 23, 1932, and the Great Depression. To help save Donnelly-Kelley, whose payroll had dropped from 120 to 30, John suspended his studies and came home to run the family business.

In the late 1930s, when John learned General Motors was looking for a mirror that wouldn't glare at night, he wondered if Donnelly-Kelley could make them. The company began working on a process in 1939.

Then came World War II. During the war years, the company transformed its decorative mirror capabilities into the production of specialized lenses and mirrors for military applications, including gunsights and submarine periscopes, developing a process for vacuum-coating glass.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos