The Story of the Shop that Dedicated Itself to the Rotary Engine

A rotary engine usually has two spark plugs for a controlled, more-powerful burn. So it is that we find ourselves in an Anaheim ice cream shop, located in the shadow of Disney's Magic Kingdom, watching two men spark a flame-front of speed. They are totally unalike: one a short, Japanese racer straight from the flanks of Mount Fuji; the other a rangy, American ex-Air Force mechanical genius.

There is a language barrier. There are cultural differences. They are from different worlds. Yet, somehow, both men feel the same pulse in their veins. It is the offbeat whomp of an engine unhappy about idling in the pits. It is a banshee scream at the Bonneville salt-flats. It is the Racing Beat. This is its story.

Fifty years ago this May, Mazda launched the production version of the Cosmo, a unique sporting coupe that took Felix Wankel's rotary dream and made it a practical reality. A relatively rare car these days, there are just a few Cosmos (badged as the 110S for export) scattered around the country, one of which resides in the basement of Mazda's Irvine Research and Development headquarters. It has a twin-rotor 10A heart restored by the Racing Beat crew.

If you have triangles on the brain, Racing Beat has legendary status.

Racing Beat. If you've got triangles on the brain, the company already has legendary status. If you're a more casual fan, you may not realize how interlinked this small California-based shop is with Mazda's identity. Stand in that R&D basement next to the classic 110S and cast your gaze over the rows of historically significant vintage racing Mazdas. Seemingly every other machine carries the Racing Beat logo, from salt-pitted Bonneville land-speed record-holders to IMSA-prepped RX-7s.

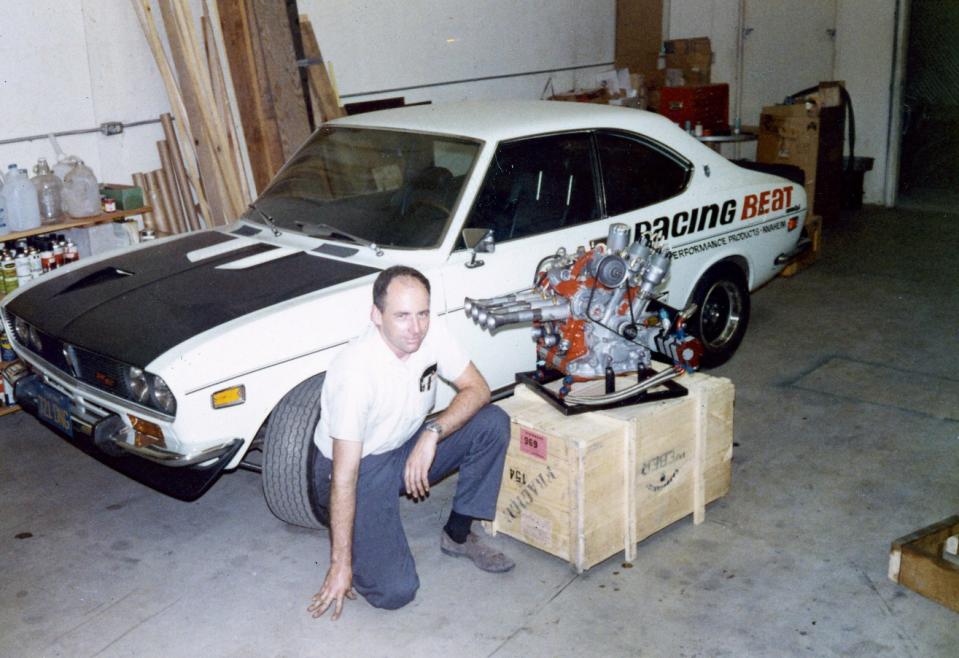

Closest to the door is where the Racing Beat story begins, with a 1973 RX-2 prepared for our sister publication, Car and Driver. Ever-persuasive executive editor Patrick Bedard convinced the accounting department to loosen the purse strings enough to build and campaign an entry in IMSA's Racing Stock (RS) series. For the roll-cage and other safety gear, Bedard turned to Roy Woods Racing. For the engine, he went to Racing Beat.

Racing Beat's two original founders in that Anaheim ice cream shop were Takayuki Oku and Jim Mederer. Mederer passed away last December, but Oku-san is still a regular in the Racing Beat offices. I called him up to speak about the early days.

"In the early 70's I owned a small race business with my brother on the outskirts of the Fuji Speedway Japan," Oku says. "I was interested in gathering mechanical, engineering and business knowledge from the more-advanced US racing scene and then made the move to Los Angeles. I asked who I should see in the US and was told through a friend to seek out a man that was working for the Shadow CanAm team by the name of Jim Mederer."

Shadow Racing Inc. began competing in CanAm in the late 1960s, with Jim Mederer joining the team in 1969. It was his first job after serving in the Air Force in Arizona, and he worked on the Mk1 Shadow, with its immense Chevrolet V8 engine.

Oku-san came to racing from a much smaller-displacement direction. "I was racing a Honda 600cc sports car in amateur racing classes and followed the early development of rotary-powered cars as they were released in Japan. Sometime in my early meetings with Jim Mederer we spoke about this engine and he showed interest."

In factory form, Car and Driver's RX-2 made 95hp. Such a figure seems relatively feeble by modern standards, but the RX-2 only weighed a little over 2200lbs, and had excellent weight distribution. With a four-barrel carburetor as standard, it looked like it could be competitive.

Mederer's genius assured that it would be. While tuning a rotary engine was basically witchcraft to racing engineers used to the well-mapped piston engine, Racing Beat's chief engineer had an instinct for getting Mazda's small-displacement oddball to breathe well. Working within IMSA rules, he shaped, smoothed, and added enormous auxiliary intake ports to the side of the rotor housing. These were so large that he had to leave a metal bridge in place splitting the port so the corner seal of the rotor didn't disintegrate. The bridge-ported engine made 198hp, and when fitted with a racing exhaust, power bloomed to 218hp at 8400rpm.

The resulting RX-2 was a screamer in both the figurative and literal sense. Oku reports that when Mederer was performing clandestine dyno-runs in his garage, you could hear the sound at least three miles away. Bedard easily took pole position in his first outing an Pocono Raceway in Pennsylvania, but the RX-2 subsequently lunched its differential. IMSA, sensing an unfair advantage under the little rotary coupe's hood, piled on a massive 300 lb penalty. It didn't matter – the RX-2 won at Lime Rock in July and Road Atlanta in September. Mazda's racing reputation in the US was born.

The RX-7 is still the most-winning model ever in IMSA history.

Racing Beat would go on to compete in every variety of racing, from NHRA dragster events, to IMSA GTU and GTO classes. In 1980, the mightily box-flared Racing Beat RX-7 GTU posted a dominating eight wins out of a twelve race season, securing the championship. The RX-7 is still the most-winning model ever in IMSA history, due in part to the efforts of the Racing Beat team.

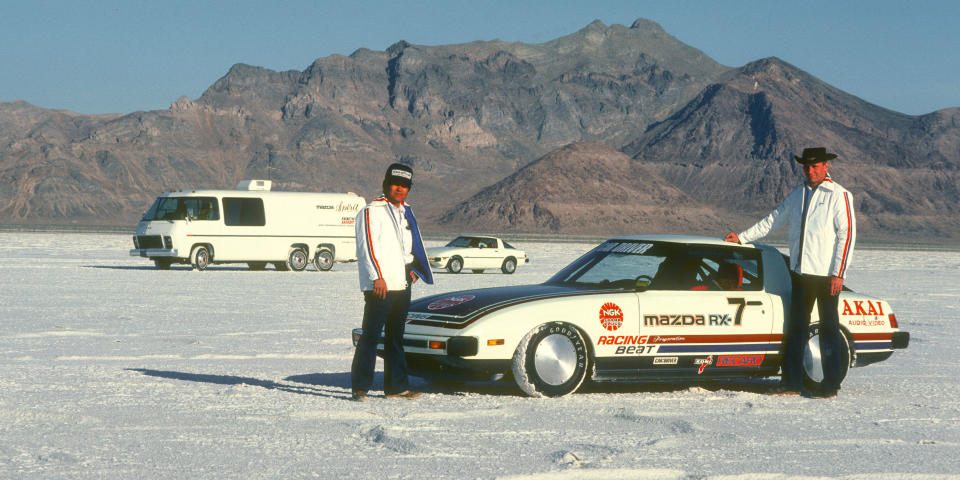

Meanwhile, at Bonneville, Racing Beat was pairing their circuit-racing successes with records on the salt. Red-and-blue-liveried Racing Beat machines began setting the bar in 1974, with another Car and Driver partnership hitting 160.3 mph in a tuned RX-4. The first-generation RX-7 arrived in 1978, and again set a record of 183.9 mph thanks to both improved aerodynamics, and further unlocking of rotary potential.

Really serious speed arrived in 1986 with the second-generation RX-7 (FC-chassis) and turbocharging. Racing Beat adapted GTP-class competition parts from Japan, reworked the fuel injection, added twin-turbocharging, and built a trunk-mounted ice-water intercooling system. Power was a staggering 530 hp at 8500 rpm: good enough for a 232.753 mph pass backed up by a 244.132 mph pass in the opposite direction.

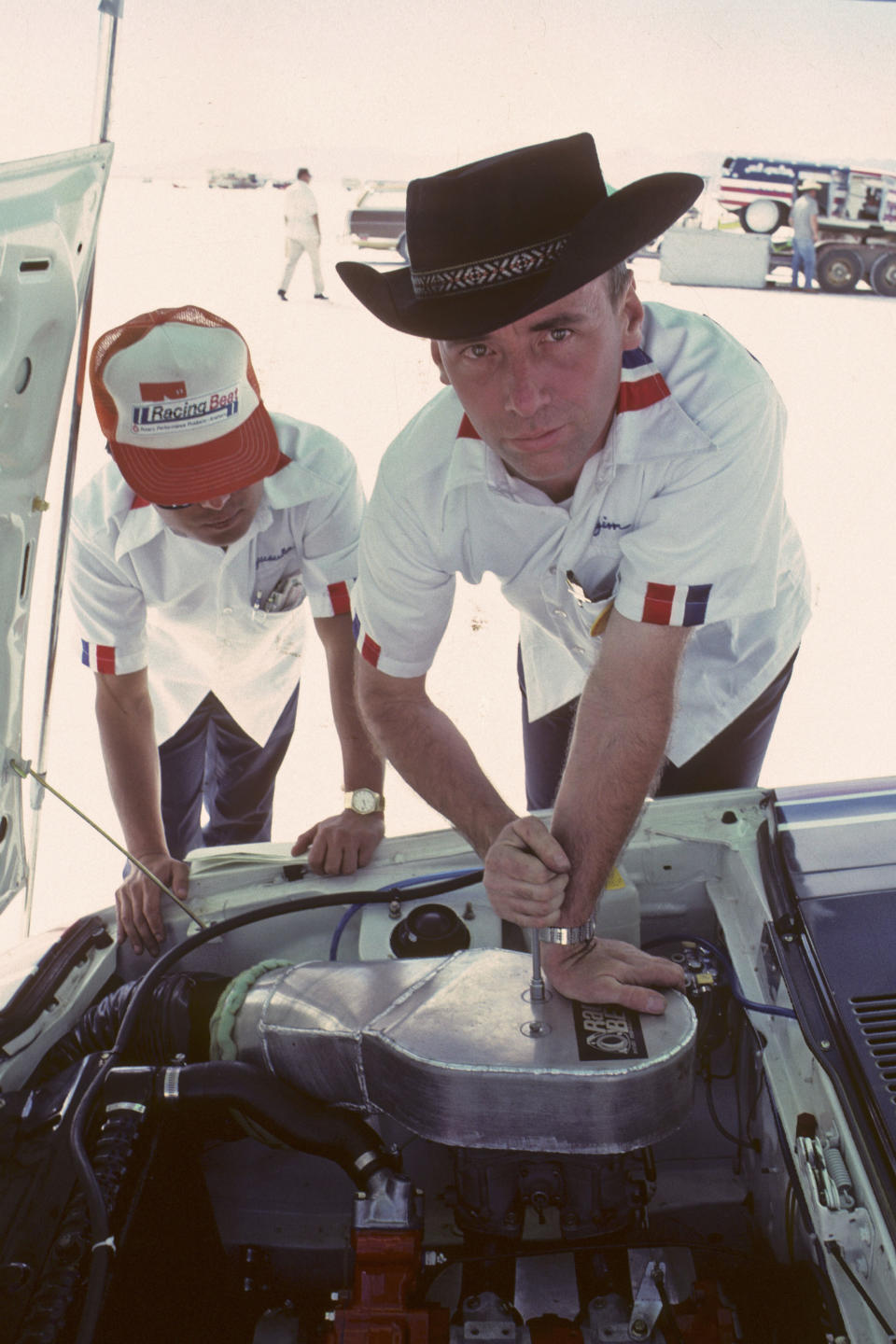

But the Salt Flats can be harsh. In 1992, the Racing Beat team returned to push the bar even higher with a 760hp three-rotor engine crammed into a third-generation RX-7. With chief engineer Jim Mederer at the wheel, the white Racing Beat RX-7 headed off, aiming to hunt down the production record of 241 mph. When the car hit 220 mph, it shimmied, spun to the left twice, and went airborne, flipping and landing on its roof.

Video footage of the crash is terrifying, showing the RX-7 shredding itself on the salt, then catching fire. Mederer coolly frees himself from the wreck, crawling backwards through the cage, and nonchalantly reaches back into the cockpit to pull the fire-suppression systems.

Rains in 1993 and 1994 prevented Racing Beat from making a second attempt at the record, but Oku-san says the team was determined. "We had a commitment with Mazda to attempt a land speed record; we knew we couldn't stop the effort after the failed attempt. The car was repaired and wanting a change from the past we painted the car black with blue stripes and gave it the name 'Back in Black.' Jim asked if I trusted his abilities as a driver and suggested he step aside if I wanted to hire a professional – but I told him that he was the man to drive the car."

And drive he did. The subsequent class record of 242 mph average speed still stands today.

Beginning in the early 1990s, the team began tuning the Miata.

Along with racing and record-setting, Racing Beat offered products which ordinary Mazda fans could appreciate. RX-7 owners have long been able to tune the suspension and performance of their rotary machines with Racing Beat upgrades and, beginning in the early 1990s, the team began tuning the then-new Miata as well.

Racing Beat's direct partnership with Mazda also grew over the years. The Protegé MP3 featured Racing Beat tweaks, and set the stage for the later Mazdaspeed Protegé. Racing Beat also developed several turbocharged applications for the RX-8's Renesis engine, though those never made production.

When Mazda wanted to make its Furai concept car a reality, it was Racing Beat that built its 450hp three-rotor engine, crowning things off with a hand-formed, rotor-shaped exhaust. While most concepts are static, the Furai had a genuine rotary heart.

But, as we all know, the Furai burned during testing while on set at Top Gear in 2008. The last RX-7 ever produced for sale in the US was built on December 27, 1995. The RX-8 went out of production a half-decade ago, and a rotary-powered Mazda replacement doesn't seem imminent.

"The future for the Mazda tuning industry is uncertain as the MX-5 ND is the only true sports-car offered by Mazda," says Oku-san. "We'll continue to support Mazda's tuning projects for new MX or CX applications as requested. However, the recent passing of Jim Mederer has certainly left a void in the heart of Racing Beat. He will be missed."

True, a spark is missing from the rotary world, and the future seems murky. But in terms of accomplishment, heritage, and blazing a trail for Mazda's mighty little engine that could, the team Takayuki Oku and Jim Mederer formed has created a lasting legacy. We don't know what's next for the rotary, but the Racing Beat goes on.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos