Study Calculates EVs Have Higher 'Real World Refueling Cost' Than Gas Vehicles

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

If you've been paying attention to the development of electric vehicles long enough, you know that there are endless factors when calculating just how clean or dirty or cheap or expensive they are.

To give buyers an estimate, the Anderson Economic Group has put out a paper trying to figure out the real-world cost, in time and money, of making the switch from gas to electric.

While the study authors did point out a fair number of legitimate factors that make charging EVs more time-consuming than getting gas for your car, what they did not do was publish an honest and realistic look at how easy it is to charge up for some people. It's an exercise in finding convenient ways to minimize the benefits and highlight the negatives.

The latest "Electric vehicles are scary!" study is out, and this one is a doozy. A new paper from the economic consulting firm Anderson Economic Group (AEG) does some novel things as it tries to comprehend the full spectrum of costs associated with making the shift away from a gas-powered vehicle to an EV. The trouble is that the authors can't hide their biases in their quest to tell everyone that gas vehicles can refuel in less time than it takes to charge an EV.

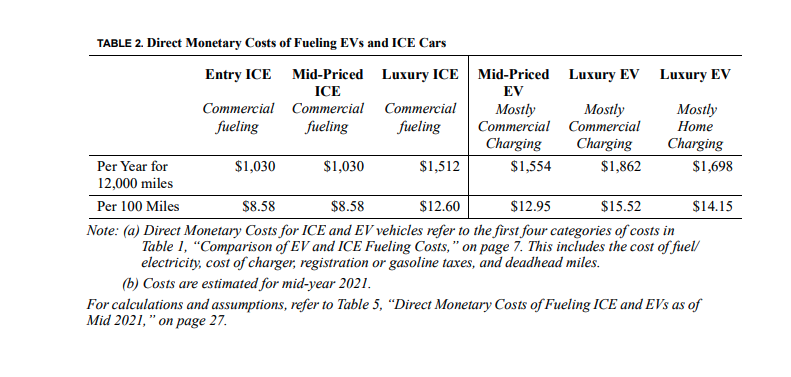

For example, based on gas prices in Michigan, where AEG is based, the study says the "direct monetary cost to drive 100 miles in an internal-combustion (ICE) vehicle is between $8 and $12, and in an EV is between $12 and $15." That sounds alarming, and the results show that no matter what, it costs more to refuel using electricity than gasoline.

But take a closer look at Table 2, and you'll see that three types of gas-powered cars are listed: entry, mid-priced, and luxury. For the EVs, there are also three columns, but they include one mid-priced and two luxury EVs (one that's "mostly" charged at home, and one that's more often charged at a public charger). In other words, any cost benefit from buying an entry-level EV is missing from this table.

More important is noting that the study assumes odd habits for an EV driver who "mostly" recharges at home. How odd? The study assumes that it takes 2.5 minutes a day to charge using an installed home charger. This feels a bit too long, but if we accept their assumption and use an average 30-day month, we can see how they calculate that charging at home eats up 75 minutes of time a month. But the paper doesn't use 75 minutes as a home charging example. Instead, it also assumes people with home charges actually conduct 40 percent of their charges at a public, commercial station. This, then, allows the study to claim that they spend 4.5 hours a month charging their car.

At-Home vs. Away-from-Home Charging

Being able to charge at home is key to the ownership-cost equation, and we would expect that the charging ratio of many EV owners is more like 90/10 percent in favor of at-home charging. Over the past two years, our long-term Tesla Model 3 is running at a 55/45 percent split in favor of at-home charging, and we would expect our figures to be on the high side of commercial charging as ours is constantly driven by people without a 240-volt hookup at home and also going on long trips.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos