The Success of Mitsuoka, Japan's Custom Car Company That's Too Weird to Die

Immediately you can sense something is off.

The vehicle in front of you has the face of an Eighties K5 Chevy Blazer, but the bow-tie badge is missing and the proportions are all wrong. That Blazer was never this small, and neither was it a four-door hatchback. The vibe is friendly and familiar, yet at the same time this is something dredged out of the uncanny valley. From Toyama city, 250 miles northwest of Tokyo, comes the Mitsuoka Buddy, the latest from the most unlikely defender of Japan’s coachbuilding heritage.

This story originally appeared in Volume 12 of Road & Track.

SIGN UP FOR THE TRACK CLUB BY R&T FOR MORE EXCLUSIVE STORIES

Hand-built automobiles are usually expensive, European, and exclusive. The Buddy is mostly the last of these. Essentially the spirit of a big-body, old-school SUV grafted onto a Toyota RAV4, the Buddy starts at $45,000 for the entry-level model and is sold out for the next two years. You likely couldn’t get one anyway: Mitsuoka sells cars only in parts of Asia and Europe.

Yet the Buddy and the rest of the Mitsuoka lineup are more than just some oddball curiosities from the land that gave us Pokémon and Hello Kitty. Mitsuoka is Japan’s youngest automaker, but it is carrying forward handmade traditions that stretch back more than a century. Today the Japanese car industry is largely represented by the streamlined mass-production efforts that went into the Toyota chassis that underpins the Buddy. Mitsuoka stands alone, providing its customers with unique hand-built vehicles that are still within the grasp of the average consumer.

Japan’s first foray into series automobile production was the Mitsubishi Model A. From 1917 to 1921, just 22 of these luxury sedans were built, each one featuring a closed rear compartment finished with lacquered white cypress. The Model A was not a commercial success, but it did mark a milestone in the rapid modernization of Japan’s industry.

By the Sixties, Japanese automakers had come into their own, and the flagship designs were handmade. The Toyota 2000GT, now established as the most collectible Japanese classic, was hand-built in cooperation with Yamaha. The Cosmo, Mazda’s first rotary-powered car, left the Hiroshima factory at an average rate of one per day, owing to the labor required in its handmade construction.

It would take until the end of the decade for Japanese sporting cars like the Datsun 510 and 240Z to reach ubiquity. In the meantime, many Japanese car enthusiasts adopted European marques: Jaguar, Alfa Romeo, MG, Triumph, Porsche, and Abarth-tuned Fiats. Specialist garages soon cropped up to support these imports, and in February 1968, Susumu Mitsuoka founded the company that bore his family name, opening Car Shop Mitsuoka Jidōsha shortly afterward.

Jidōsha is the slightly more formal word for car in Japanese, analogous to automobile. The name is a slight hint to Mr. Mitsuoka’s ambition. He possessed a particular enthusiasm for British cars and was soon servicing various marques for owners in the Toyama prefecture.

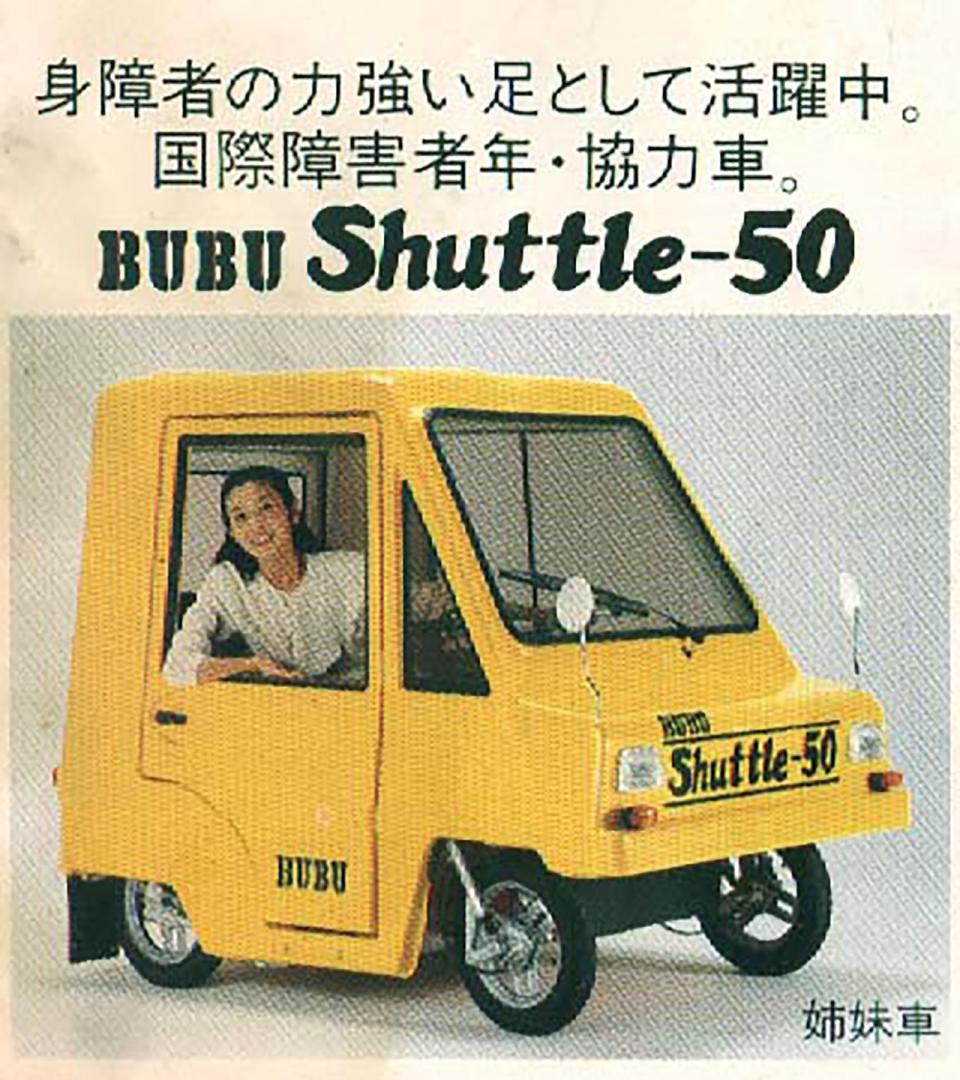

Among the vehicles brought to the Mitsuoka garages was an Italian microcar, its make and model now lost to time. Parts to complete the repair couldn’t be found, but inspiration could. Perhaps spurred by the simple construction of the microcar, Mitsuoka decided to build his own car from scratch. By 1982, he had succeeded.

The first car Mitsuoka Motor Co. produced was called the Bubu Shuttle 50. Bubu is a Japanese child’s word for a car, and the Shuttle, powered by a 50-cc engine, was tiny, slow, and toylike. However, it was also forward looking for the time, being specially made to accommodate a driver using a wheelchair. In modern times, almost every Japanese manufacturer builds wheelchair-accessible models.

Mitsuoka followed up with the three-wheeled Bubu 501 and the absurdly boxy 502. In addition to looking like backdrops in a Studio Ghibli movie, these small-displacement machines could be driven with a basic scooter license. Sales were steady, supplemented by Mitsuoka’s other divisions that established used-car dealerships in the area. The company grew.

Its real breakthrough came in the mid-to late Eighties. The microcar market was drying up as new safety regulations came into effect in Japan, and the small factory needed new work to keep going. On a trip to Los Angeles, Mitsuoka saw several examples of the kit-car craze popular at the time. He decided his company’s future would be in building replica cars.

The first of these was the Bubu 505-C, again a 50-cc-powered car, but here resembling a miniature Jaguar SS100. The later Bubu Classic SSK was more typical of the replica-car era, incorporating prewar Mercedes design elements but riding on a Volkswagen Beetle chassis. The Bubu 356 Speedstar was, as you’d expect, a copy of a Porsche 356 Speedster.

None of these were particularly groundbreaking efforts, but they did mark the beginning of the Mitsuoka recipe: Take an ordinary consumer car, infuse it with the spirit of a vintage car, and the result is something that looks unusual yet is also easy to live with. If you can buy a car that looks like something Cruella de Vil would drive and still get oil changes at your local Nissan dealership, wouldn’t you be tempted? Mitsuoka did just that, creating the neoclassic Le-Seyde based on the fifth-generation Nissan Silvia.

The timing was perfect. Japan was in the midst of a neoclassic craze, with the likes of Nissan’s retro-inflected Pike Factory cars generating huge waitlists. When the Le-Seyde went on sale in 1990, all 500 were spoken for in 72 hours.

Mitsuoka followed up this success with the Viewt, its longest-running nameplate. Essentially a Nissan March restyled to resemble a Jaguar Mk II sedan, the Viewt perfectly epitomizes what Mitsuoka does best. Underneath, it’s an inexpensive compact sedan, thrifty on fuel and smartly sized for narrow Japanese side roads. On the exterior, it’s a charmingly quirky adaptation of Sixties British aesthetics.

It is also a truly special vehicle. Luxury automakers like Bentley and Rolls-Royce often issue press releases extolling the craftsmanship that goes into building their cars. Likewise, each Mitsuoka represents the work of two craftsmen. Usually working in pairs, factory workers at Mitsuoka complete one or two cars per day. Depending on the model, finishing a single car can take 30 to 60 days.

The process begins with the arrival and disassembly of the vehicle that will form the underpinnings of the completed car. Disassembly is also where new workers begin their training at Mitsuoka, gradually moving up to assembly, welding, and painting as skills progress. The production facility staff is quite small, with just 80 employees spread out between design, manufacturing, and management.

The factory layout is entirely unlike a modern assembly line. It’s more like a restoration facility. Workers shape and weld steel panels, the cars are individually painted in the paint booth, and final interior assembly is done by hand. There are no robots, and everything moves at a methodical and careful pace.

Mitsuoka’s right to claim its place as Japan’s 10th automaker came in 1994, with the Zero1. Resembling a Lotus Seven, this model was built entirely in-house with the exception of the powertrain, which was sourced from a Mazda MX-5.

It was not the company’s only ground-up effort. The follow-up to the Zero1 arrived in 2007 in the form of the outlandish Orochi, a mid-engine sports car that is not so much uncanny valley as it is Mariana Trench. Powered by a 3.3-liter Toyota V-6, the Orochi was not really a performer but a statement on creativity. You either love it or hate it; there’s no neutral ground.

The Orochi’s challenge was not so much its polarizing styling as the price tag for its bespoke chassis. The car proved Mitsuoka’s design and manufacturing capabilities, but by 2015, the company returned to a more traditional coachbuilding arrangement.

Today Mitsuoka offers a lineup of six vehicles, each one based on a conventional car. The Viewt, Galue, and Ryugi all are four-door sedans with elements of Jaguar, Bentley, and Rolls-Royce. The Himiko roadster resembles a Morgan Plus Four and is based on a modern MX-5; its wheelbase is lengthened by some 23 inches to achieve the long-nosed silhouette.

More recently, however, Mitsuoka has looked to American car culture for inspiration. General manager Minoro Watanabe spent time in California during his youth and brought back a desire to infuse SoCal car culture into Mitsuoka designs.

The first, built to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Mitsuoka, was the Rock Star. Like the Himiko, the Rock Star is based on the current MX-5, though in this case with the standard wheelbase. The bodywork is meant to evoke the Corvette Sting Ray of the Sixties, and initially only 50 were made. Demand was such that the production run was extended to 200 cars available in 30 different paint colors. In the U.S., the MX-5 Miata comes in just seven shades.

Mitsuoka sources its MX-5 foundations not from Mazda directly but from a local Mazda dealer. The company also sourced one Canada-spec MX-5 and created a one-of-one left-hand-drive model, holding a lottery for the chance to buy it. Each ticket cost the equivalent of $4355, and the selling price of $86,274 was more than twice that of a standard Rock Star.

A Buddy is more reasonable but no less interesting. What’s perhaps even more interesting is what Mitsuoka’s range represents when taken as a whole.

It is a small, niche company, a minnow in the ocean of Japanese automobile manufacturing. Yet it has a 50-year history of success, and its products are still in high demand. Some of its quirkier efforts don’t entirely translate to a broader audience, but cars like the Buddy and the Rock Star offer understandable appeal.

When compared to the homogenous state of the rest of the car industry, Mitsuoka provides a rare spark of creativity unbound by the practical restraints of mass manufacturing. Its vehicles are not for the masses, and they are built with an exceptional level of care and attention.

You have to wonder if an idea like the Buddy could work on this side of the Pacific. Whether consumers grown weary of angry-faced crossovers might be willing to wait months for a car with all the practicality of a Toyota blended with a dash of nostalgia. Whether people would pay a premium to have a wider range of colors and standout styling.

Mitsuoka probably couldn’t happen here. But for a few lucky customers in Japan and a handful of places around the globe, a special car built by the hands of craftsmen is within reach. They can look in their driveway and see something relatable and charming parked there. A Buddy, a four-wheeled friend.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos