Tesla’s Little-Known Prehistory

Seventeen years ago on a sunny fall day, we were testing our usual phalanx of cars at the old drag strip at California Speedway when the future of transportation rolled onto the tarmac. It was a bright yellow two-seat roadster and on its side was written, “tzero,” the mathematical point at which it all begins.

Earlier, I’d gotten a call from Tom Gage, president and CEO of AC Propulsion, asking if we had any track time coming up and whether they could track test a car they’d been working on. I’d written about AC Propulsion before and all the cool and interesting things they were working on. It seemed everyone there had a PhD from CalTech and I liked hanging out with people like that, so I was glad for the opportunity to hang out some more. I couldn’t have known, however, that the thing they were bringing out would eventually become the first Tesla, the company that is now the world’s most valuable carmaker.

They had a truckload of CalTech geniuses with them, including company founder Alan Cocconi, the king-brains behind everything. As a consultant for Aerovironment, Cocconi had worked on the GM SunRaycer solar car that won the 1987 World Solar Challenge race across Australia. He also worked on the GM Impact electric concept car that would itself become the EV1. And then he help build another Aerovironment project, the flying mechanical pterosaur that starred in the IMAX feature film, On The Wing. To even grasp how anyone could make a real-life-looking, 18-foot-wingspan physically accurate pterosaur and make it fly is beyond me, as was the circuitry Cocconi soldered together to make the AC drivetrain of the SunRaycer/EV1/tzero.

So it was cool to be there to see at least one of those creations, the tzero electric roadster. There was even a Hollywood star present in the person of actor Tony Shalhoub, who played Monk and other lovable roles and who was one of several Hollywood types interested in EVs very early on (Tom Hanks was another ACP customer, but let’s not descend into name dropping here).

We put all our test equipment on the tzero and ran it down the track. ACP had said it would do a 3.7 0-60, but we got a 4.1. Cocconi said it was a software glitch in the traction control, that he fixed and told us he got the claimed 3.7 afterwards. The 0-60 figure you see nowadays for the car is 3.6 seconds. (The older I get, the faster I was.) Regardless, those are remarkable for a production-intent electric car in those days.

The AC Propulsion connection is fairly well known among the Teslarati, and we’ll get back to that and the ascension of Tesla in a second. First, let’s go farther back. What might not be known is where the tzero itself came from. And for that we go to Brighton, Michigan, to an engineer named Dave Piontek who was innocently building sports cars in his garage way back in the ‘80s and had no idea the part he’d play in automotive history.

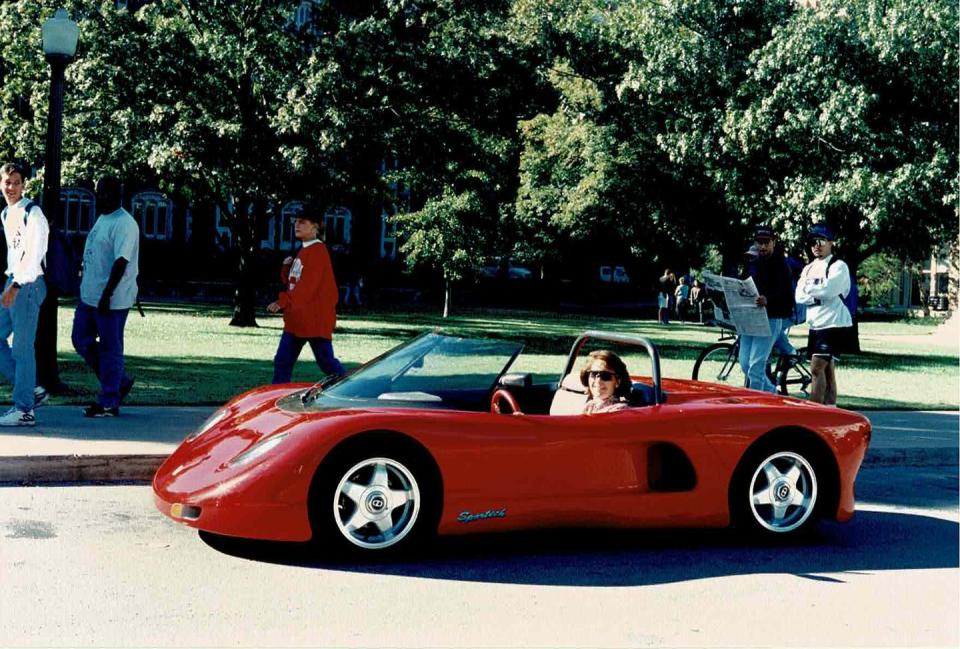

Piontek was building a cute two-seat carbon fiber/Kevlar roadster he called the Sportech. It was powered by your choice of a couple different Suzuki GSX-R motorcycle engines. With a curb weight of 1,100 pounds, and with as much as 250 hp, it had an absurd power-to-weight ratio of 4.4 pounds per hp.

“It was a hell of a lot of fun,” said the now-retired Piontek when we caught up with him by phone driving his motor home around Florida. “I completed the original car in 1989 and I took it to the Detroit Autorama and got quite a bit of attention there. It won an award for design and originality. I painted it in my garage, I literally did probably 90% of the work myself. For a one-man band, it was pretty impressive.”

The only thing he didn’t do was design the swoopy, neo-Italian-looking body.

“I’m an engineer, OK, you ever see an engineer with a sense of style?”

With no budget he brought in “two kids who had just graduated from CCS” in Detroit who were working where he was at the Ford Design Center. Using discarded chunks of modeling clay that Ford was going to throw away or donate to CCS, the kids made the body. Piontek then brought in “a couple of guys from the plastic shop at Ford who were moonlighting,” and they made the fiberglass mold. Piontek had already engineered the chassis, so with all that in order, he started building car bodies. To get the engines, he turned to his brother, another exec at Ford, who had been tinkering on his own time with Suzuki motorcycle engines. The brother took an 1100-cc engine and “punched it out” to 1325 ccs. Put all that together and voila—sports car!

The first one was 1,235 pounds because Piontek says, “I kind of over-designed the chassis.” Adding nitrous to the engine for another 25 hp countered the weight.

“That car hauled ass!” he said.

Piontek registered it for the street in Michigan, drove it to work, drove it all over. When he got a little more money, he’d build another one. In all he built seven cars, the last one was titled in 2004.

Alright, you’re saying, how does this lead to Tesla?

One of Piontek’s Sportechs was acquired by Dr. John Fagan, a professor of electrical engineering and computer science at the University of Oklahoma. Fagan was the kind of professor you wish you’d had in college. He was making all kinds of cool cars and getting students involved, and ultimately he was racing some of his creations in a series made just for EVs. Fagan was given a Piontek Sportech from the Hawaiian Electric Company. It had a motorcycle engine in it, which he replaced with an electric motor and controller from AC Propulsion. This would have been in about 1997 or so. AC Propulsion was specializing in ultra-efficient motors, controllers, inverters, and all those other electrical engineering things that make an EV go. In an era where any electric car was referred to as “a glorified golf cart,” AC Propulsion was selling highly efficient hot rod drivetrains.

“They were designing new power electronics with the integrated charger and an induction motor to go along with it,” said AC Propulsion’s VP of Engineering Paul Carosa. “The idea was to just focus on development of the drive system, particularly and especially with this idea of the integrated battery charger, which was pretty unique. It’s still kind of unique, actually, there might be somebody doing it, but it’s not really widespread. The concept basically reutilizes a lot of inverter components, you know, the IGBTs and motor windings to make a high-power battery charger, repurposes them and makes them dual purpose, to function on the electronics and the motor. At that time it was 20 kilowatts—20 kilowatts was much higher than anybody was doing at that time.”

It was one of these hot-rodded AC Propulsion drivetrains that Fagan put into his Piontek Sportech.

“We put in one of AC Propulsion’s drives,” Fagan said. “It was a badass drive. That thing had about three quarters the torque of a Tesla today.”

Fagan loved it and saw the car’s potential. He tried to promote the car and get a manufacturer to build it, but ultimately didn’t find anyone willing. Eventually Hawaiian Electric wanted their Piontek back and that was the last Fagan saw of the Sportech.

However, back at AC Propulsion, Alan Cocconi and Paul Carosa and team saw what Fagan had done and were intrigued. Or maybe they were already working on it, but they got a Piontek Sportech from Piontek (his company was called Fun Car Company) and put their own drivetrain in it and (drumroll) that was the first tzero.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos