Tested: 1995 Land Rover Defender 90 Goes Nowhere, Man

Originally from the July 1996 Issue.

John, if we ever get home, let me book you an appointment for a very thorough CAT scan." So said senior editor Phil Berg, upon observing the first of three 1000-foot cliffs we would somehow have to surmount in southern Utah.

I felt that Berg had possibly overreacted. After all, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark traversed 4000 miles of similarly difficult topography. (I thought it unwise to mention Lewis's subsequent alcoholism, his drug addictions, and his manic depression that preceded his suicide at age 35.)

The red-and-white-striped cliffs, mute and deeply ominous, constituted a kind of scenic Berlin Wall, separating us from what is semiofficially the loneliest place in the lower 48 states.

Getting there was our goal.

For your information, the Loneliest Place is not far from Spooky Gulch, Rat Seep, and Deadman Ridge and is a location we felt we needed to investigate because we are restless drivers ever in search of manly adventure, because we are pros at doing the most important kind of nothing, because our readers demand conceptual brilliance, and because we wanted to purchase L.L. Bean camping gear wholly at our publisher's expense.

Of course, simply identifying the Loneliest Place and driving there are two very different kettles of carp. Basically, it’s the difference between locating Kathy Ireland (try page 80, Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue) and persuading her to bear your children in an aluminum doublewide parked in poorest Paramus.

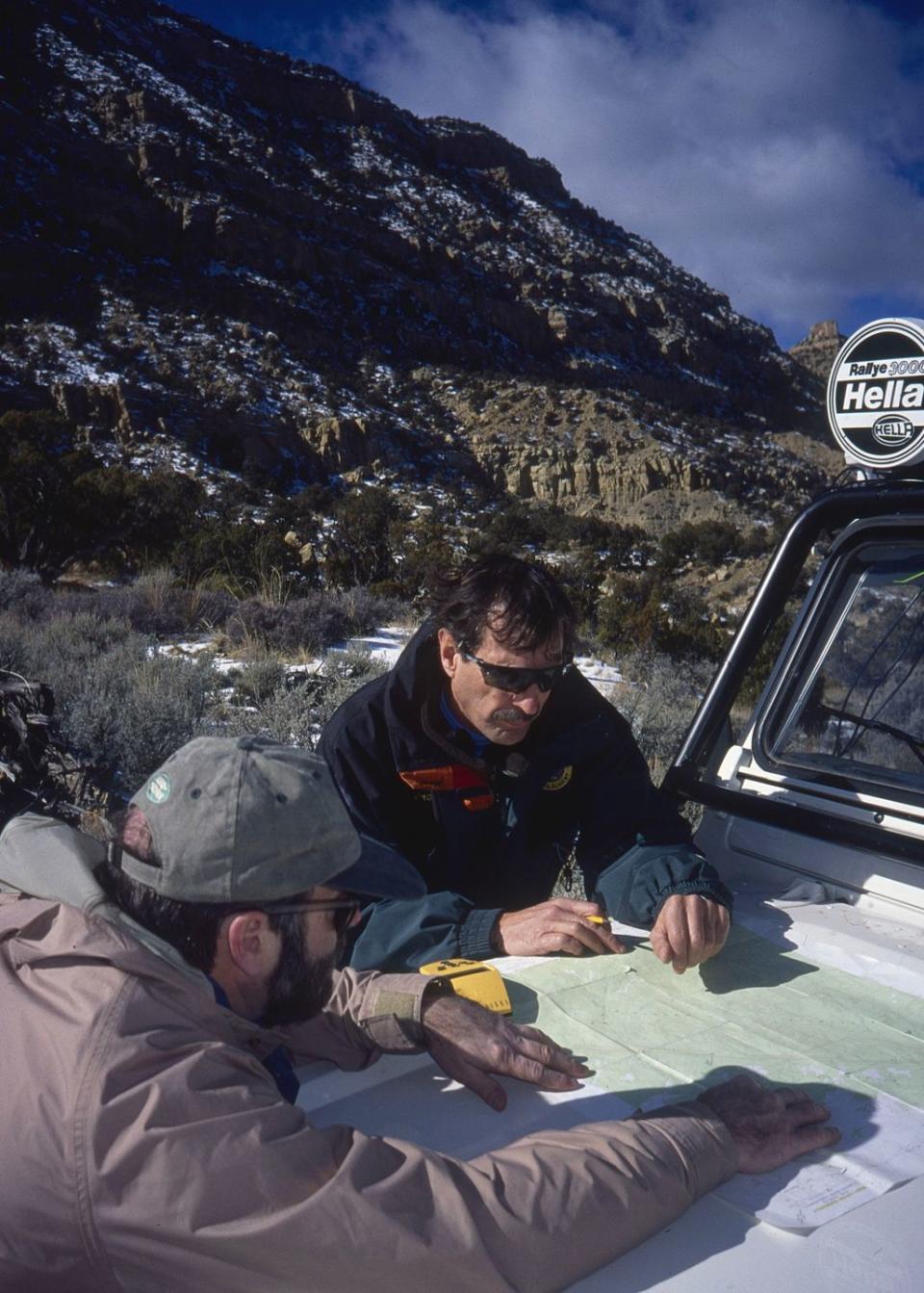

Well, that's not exactly right. Locating the Loneliest Spot actually took longer than placing our bodies there, although it decimated fewer thigh-muscle groups. We first enlisted the cunning of Poppet Seymour (she of Cartographic Technologies in Brattleboro, Vermont, and whose name gave rise to endless speculation around the campfIre) to pinpoint the lone, lower-48 locus that: a) is farthest from any U.S. citizens as determined by the stupendously inaccurate 1990 census, and b) is farthest from any paved roads. This assignment cost Poppet Seymour three months, a wrecked Windows '95 program, and some of her hair. Meanwhile, we fattened a file with aerial photography, satellite images, U.S. Geological Survey reports, and various permits from both the Bureau of Land Management ("Tell us once again exactly what you plan to do in there?") and the State of Utah ("Please don't tell us anything about what you plan to do in there").

Lighter in purse but essentially uncowed, we did identify the Loneliest Spot. At least on paper. It's at 37 degrees, 24 minutes, 49.5 seconds north, 111 degrees, 16 minutes, 47.03 seconds west (see map). This happens to be in Basin Canyon, on Fiftymile Mountain, in the Kaiparowits Plateau in south-central Utah. Here, within a 3D-mile radius, you will find no homes, few footprints, and no cable TV. What you will find is an astronomical number of cow-pies, thanks to cowboys who loose their cattle to feed on land maintained by taxpayers. (As Don Irnus said, "Truth is beauty, and beauty is always better-lookin' if you sprinkle some natural ugly around it.")

You will also find nothing edible here, unless your Land Rover runs over a prickly pear or a high-desert hare the size of a Disney character. (We would perform this function later.)

The closest real settlement is Escalante, Utah, population 751. The nearby village of Boulder was the last town in the continental U.S. to be reached by an automobile, which is curious because there are today no automobiles here at all, just pickup trucks. (A local rancher told us, "You don't drive a truck 'round here, preferably a Dodge Ram, then you're either a damned tourist or some kind of toad raper.")

In fact, the nearby Henry Mountains, later to be immortalized by a candy bar, repose in the last area in the continental U.S. to be mapped.

Our party (well, they called the Donners a "party") initially mobilized two vehicles. We figured two would be necessary so that the Warn winch on one could be deployed to yank hard on the bumper of the second, which a C/D employee would probably have buried in quicksand. (This could really happen. The official BLM advice on this exciting topographic jackpot was not to panic: "You will most likely not sink past your waist," we were assured.)

For this expedition, C/D could deploy any 4wd vehicle it fancied. Berg and I naturally considered a Lambo Diablo VT but discarded the idea when we remembered its pedals are too narrow for cowboy boots. Far rarer was a $37,520 Land Rover Defender 90 hardtop, complete with a top speed of 84 mph and a dashboard designed when Winston Churchill was still cursing the Huns. The V-8-powered Defender is the undisputed British bull terrier of off-roaders—the perfect cross between a Mercedes Gelandewagen and a 1951 Willys Overland. Pop it into first gear, low range, and this cur will claw halfway up the Washington Monument with no driver at the wheel. (Later, near Coyote Hole, I nailed a two-foot-diameter boulder with the Defender's right-front All-Terrain T/A. The impact launched Berg-no seatbelt, he was hunting for a Diet Pepsi-partly through the roof liner. Even before I could declutch, the Defender, which had actually been knocked backward a foot, resumed climbing and grinding like some sort of sandstone-eating In-Sink-Erator.)

"Also, another reason I like it," offered Berg, "is those Hella spotlights, which I'm pretty sure are bright enough to scorch the legs off scorpions."

Accompanying me and photographer Berg, whose Norwegian forebears oddly inculcated him with no useful tips on camping in the snow ("Buy a $400 bag" was the sum of his wisdom), was Tom Collins. Collins is a lanky 46-year-old Coloradan, an Ichabod Crane look-alike, irrepressibly rosy-humored but with the maniacal countenance of Dennis Hopper. His day job: chief trainer for America's Camel Trophy contestants. Almost by default, this ranks him among the nation's most canny off-road wheelmen and the human most likely to be rejected by the marines as an inequitable threat to the enemy.

"A six-foot clay escarpment got in his way today," Berg recalled, "and Tom got a kind of black scowl, like he might leap out of the Defender and just eat through."

BY VEHICLE

ASSAULT NO. 1:

From Escalante, we drove south-past Devil's Garden, Buckaroo Flat, Early Weed Bench, Peek-A-Boo Gulch, and Cat Pasture—cruising at 40 mph atop the inexplicably smooth Hole-in-the-Rock Road, created in 1880 by righteous Mormons who possessed no Coors whatsoever. This brought us to Batty Pass Caves, where we lost no time in locking the keys in the Land Rover so that zero civilians could steal anything in an area populated by exactly zero civilians. Demonstrating his finely honed outdoors craftery, Collins regained access to the Rover's cockpit by prying open the door with a five-foot-long pine bough. Amazingly, this inflicted no discernible damage.

The Batty caves are not now notably batty but were undeniably home to batty occupants around 1964. That's when two hermits began building boats there, in preparation for the watery world of wonders that would presumably pool behind the nearby Glen Canyon Dam, which was then still filling. This business failed, in part because their boats were fashioned 50 percent from newspaper and in part because the liquid portion of Lake Powell never got within 18 miles of this spot. Noted Berg, “The guy probably told his bank manager, ‘We encountered a negative buoyancy deficit.’”

Utah's Kaiparowits Plateau, home of the Loneliest Spot, was a favored hangout of eco-activist Edward Abbey and the Monkey Wrench Gang some 30 years ago. It also represented home to the Anasazi Indians 675 years before that.

For these tricky pronunciations, Berg proposed this solution: "Word association," he said solemnly. "For 'Anasazi,' think of 'Honest Ozzie.' And as for the plateau, well, it reminds me of a Polish tailor. So what you come up with is 'Honest Ozzie Kayparowitz,' who maybe ran Honest Ozzie' s Factory Outlet Wholesale Direct to You."

This remarkable treatise was followed by an equally remarkable duration of silence. Because of the Defender 90's iguana-like grip on solid rock, we were able to bump along another three miles until the trail stopped being a navigable rut and began being pinyon pines. "We're not far from Carcass Canyon," Berg informed. "In fact, we're near a lot of places."

"Like what?" I inquired testily.

"Like, we're not far from Drip Tank Canyon, Dog Flat, Death Ridge, Butt Canyon, Fools Canyon, Scorpion Gulch, and Tarantula Mesa. See?"

I smacked the map out of his hands. This is when we nearly T-boned the foot of Fiftymile Bench. This sandstone edifice impolitely and arrogantly rises out of the mauve mesquite, all rusty, stained, and as vertical as the Eiffel Tower, if the Eiffel Tower happened to stand some 1519 feet erect in outback Utah.

"I am pretty sure this is way too icy to climb," offered Berg, who was having trouble standing.

"Too bad for us," said Collins. Then he stabbed at one of three Magellan Trailblazer XL global-positioning calculators we had on hand. "Because we're only 1.59 miles from the Loneliest Spot. And we drove here."

We climbed back into the Rover and retraced our route, searching for an approach less likely to inflict a closed head injury. Naturally, this was Berg's cue to root through his underseat convenience-store cache of Diet Pepsi.

BY VEHICLE

ASSAULT NO. 2:

To reach America's Loneliest Spot, we opted to circumnavigate Fiftymile Bench and approach from behind, where the cliffs aren't 1000 feet high. More like 750. This led us through Left Hand Collet Canyon, a 20-foot-wide crease that is a surpassingly poor passageway to inhabit during flashflood season. In winter, much of the canyon floor here is blue ice hidden from the sun by an unlikely succession of overhanging sandstone amphitheaters. The 4000-pound Defender regularly broke through, sounding like a large cowboy boot stomping a bag of fresh Fritos.

"Your body goes all stiff every time that happens," observed Berg, who later persuaded me to scramble atop the Defender so I could climb into a natural bathtub carved in the upper canyon wall. He cursed me when I used a Hella as a step. When I slipped, my arm struck the sandstone cliff face, an action that reversed my wristwatch's calendar by four days.

Through Left Hand Collet Canyon arguably 13 of the most scenic off-road miles in America—the Defender 90 proved to be every inch the unleaded-swilling billy goat we had hoped. At 1500 rpm, it bumped its way eagerly over sharp lava beds, sand dunes, river-borne detritus, ironstone concretions, domes, pedestals, balanced rocks, sandstone monoliths, stone arches, natural bridges, coal seams, petrified wood, one unfortunate desert hare whose enthusiasm for the vehicle sadly did not match our own (it was an accident), and a handful of discarded Skoal tins.

Eventually, the Defender elevated us to 6410 feet atop a boulder-strewn butte that overlooks Basin Canyon. At this point, we were 3.9 miles south of the Loneliest Spot. Still, the walk from this point was less dangerous than from the previous point. "A little inhospitable," observed Collins, our history major. "But mankind has occupied this area on and off since the birth of Christ."

This chronology was appropriate, I calculated. When the fun-loving Spanish friar Silvestre Velez de Escalante first explored here—accidentally naming a town after himself—I imagine he spent several hours surveying the surrounding terrain, muttering, "Jesus H. Christ!"

As we pitched a tent, Berg actually found a clear radio signal. It was a broadcast of the Super Bowl. In Navajo. "I have trouble imagining Native Americans rooting for Cowboys," said Berg.

At 9 p.m, we climbed into down-filled bags deployed atop three inches of granola-like snow. "About 20 degrees, I'd guess," whispered Collins. Our tent was fast filling with eructations-ode de Dinty Moore. Ten minutes passed. Then a voice in the dark asked, "Who, uh: you know, is actually holding the keys to the Defender?"

At dawn, coyotes howled. Frostbitten paws was my guess. The morning shadows revealed a new problem: Between us and our lonesomest goal stood not one but two intimidating escarpments, one of which resembled a beige Transamerica Building on its side.

Collins nonetheless predicted he could drive the Defender about 300 feet down the first rock face if he kept the thing on a 70-inch-wide chariot rut covered in slush. For no discernible reason, he was successful at this-descending in a frightening 1-mph crab-Ieft/crab-right locked-wheel ballet until the path was comprehensively obliterated by a brown boulder the size of Paul Prudhomme's kitchen. It had fallen after the last uranium prospector evacuated this area some 40 years earlier.

"Now we walk," Coilins informed. "And if you feel inclined to snap an ankle, I'd remind you that this particular 3000-square-mile area contains no medical personnel, not even with dull Swiss Army knives.”

WALK-IN

ATTEMPT NO. 1:

My plan—one of perhaps six uniquely bad ones—was to travel light. Day packs only, straight to the Loneliest Spot. How hateful a march could 3.9 miles (or 7.8 miles round trip) really represent, given nine sunny daylight hours? Even a waffle-addled tourist could average 1 mph on foot, surely.

We left at dawn. After two hours of lurching and bumbling 700 feet in the direction of hell, followed immediately by 700 feet of slogging and gasping in the direction of the celestial firmament—all of this in atmosphere with approximately the oxygen content of bouillabaisse—we had advanced exactly one-half mile from camp. Across the gaping canyon, our gaily colored tent was clearly visible and appeared to be waving at us. Scrambling on hands and knees over another 100 or so consecutive sandstone outcrops and boulders wore a butt-cheek fissure in my new Levis. When we finally came to flat surfaces, they were covered in snow and sand; it was like walking through dunes. And we were still 1400 feet below the Loneliest Place and more than a mile south of it, as the crow flies, although a crow over this terrain would require extensive flight instruction from the FAA.

The plateau here looked like the artwork for a Windham Hill album cover: buff-green tumbleweed, pinyon pines, needle-sharp yuccas, and 10-foot-tall one-seed junipers, many of them a century old. "Gnarly" does not adequately describe their trunks. More like a combination of Lake Superior driftwood and Keith Richard's forehead. The junipers' oily aroma overwhelmed even our own piquant reek.

By 1 p.m., we were whole-wheat toast. Berg and I, but not Collins, were hyperventilating, thighs and calf muscles on fire. I wanted to rent an iron lung.

"You're not exactly Lewis and Clark," observed Collins.

"More like Lois and Clark," I replied. I began empathizing with Meriwether Lewis's suicidal depression.

No choice but to tum back, just as we reached 37 degrees, 23 minutes, 44.8 seconds north, 111 degrees, 17 minutes, 55.9 seconds west, at an altitude of 6300 feet. Collins built a two-foot-high rock cairn there—probably a felony-littering infraction—on top of which I deposited my lucky 1979 Susan B. Anthony silver dollar. (Note to future explorers: Tell me what's weird about this coin, apart from the treasury ever having minted it, and you win not only the coin but also my hiking socks.)

When we hobbled back to the Defender, it was dark. Berg had adopted the peculiar gait of Fred Sanford and would subsequently miss four days of work, e-mailing this excuse: "I'll be back as soon as I grow new pulmonary apparatus." The following day, we drove the Defender to Big Mike's Cowboy Palace—on Whiskey Row in Prescott, Arizona—for a debriefing.

On the next assault, we vowed to spend an extra frigid night camped nearer the Loneliest Spot, thus affording three full days of hiking. Contemplating this second walk-in unnerved me, although I was temporarily soothed by an ad for Big Mike's "Cowboy Luau," which featured a contest called "Most Likely to Get Lei'd." Although, actually, we did not.

WALK-IN

ATTEMPT NO. 2

A month passed. Then, for our second attempt to reach the Loneliest Spot, I enlisted the support of Vermont native Michael Hussey, 33, who accompanied me in 1993 on our victorious-but-leech-infested Camel Trophy boondoggle through Borneo. He is an off-road driving instructor for Land Rover and a trained geologist, and he can make a noise with his mouth that sounds exactly like a newborn Holstein. (This later proved detrimental. Mike mooed just as we were inching along a 5600-foot-high track, and a longhorn bull charged, nearly ramming the passenger door.)

Every day, Hussey went all glassy eyed over the geology of Honest Ozzie Kayparowitz's Factory Outlet Plateau. This area is Mother Nature's own experiment in salt-water taffy shapes, carved in a Ben & Jerry's palette of colors. The reddish-brown siltstone, orange sandstone, and green clay stone are eroded into intricate swirls, icicles, cones, and rounded rec rooms.

Hussey gave me nine lessons in sedimentary- rock formation, focusing on sandstone cross-bedding. "Geologically speaking," he said, "I think God was just practicing here." As we were driving, I asked him to name the geologic eras in chronological order. He replied: "Okay, there's Pre-cambrian, Cambrian, ah, Devonian, Jurassic Park, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon."

The region surrounding the Loneliest Spot is peppered with caves of every dimension. Some still bear the petroglyphic graffiti of the Hopi and Paiute—etchings that Georgia O'Keeffe would later roughly translate as meaning, "For some big action, check out the Lansing Lugnuts." We actually did stumble across a genuine Anasazi cliff dwelling—a 15-foot-long semicircle of perfectly laid flagstones and mud mortar, with a tiny square doorway that proves these people possessed the stature of Danny DeVito. (We subsequently reported the precise location of this amazing dwelling to a BLM agent, thinking he'd chopper in an archaeological SWAT team. All he said was, "Yeah, neat.")

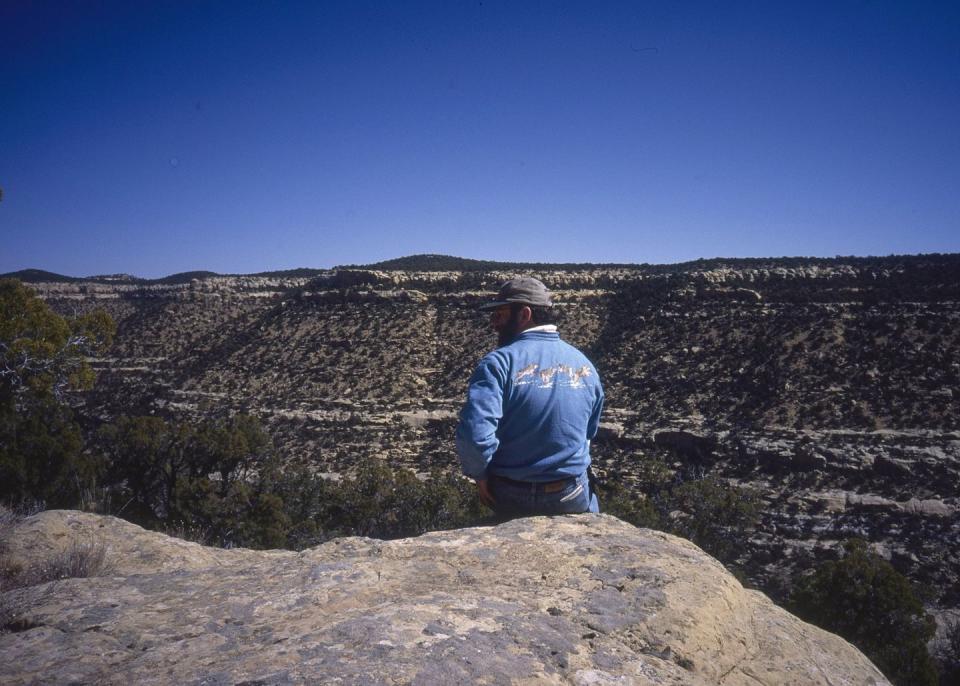

On foot, we eventually grunted and swore softly all the way to the Loneliest Spot—Saturday, March 16, 12:45 p.m., 49 degrees Fahrenheit-eating lunch there and staring at it for 30 minutes. It was a little anticlimactic, largely because the Spot looked a whole lot like several hundred other spots in the immediate vicinity—forlorn, devoid of human touch, and emanating a hostile aura, a little like Denver' new airport. We planted no flag; the BLM had warned us about littering. Had he beaten us to this peaceful place, H.D. Thoreau would still be issuing inscrutable memoranda about it and would surely have sold Walden Pond to strip-mall developers.

The march back to the vehicle nearly killed me. Whatever deity designed this region did not take into account the foibles and frailties of biped locomotion. With some prejudice, I began silently naming the impediments as our return dragged on: No Man's Mesa, Guerrero Gulch (a crash on the first attempt), Haymaker Hillock, Chevy Chase Arroyo (straight to professional therapy thereafter), Rio Vista the Vicious, Big Bastard Butte, Titanic Teats Talus, Hemorrhage Hill, Hydraulic Garbage-Truck Crusher Promontory, and Now We're Totally Screwed Plateau.

"Who's screwed?" asked Hussey.

"Ah, no one," I said, unaware I had been muttering out loud.

On the drive out, we experienced a near-head-on collision with a 4wd pickup truck—probably the only other vehicle within a 30-mile radius—being driven somewhat recklessly by a green-suited Department of Agriculture agent. He was carrying more guns and rifles than I imagined were absolutely necessary. "Boys, you do not wanna be up here if it rains," he warned sternly, although he approved of our choice of off-roaders. He reminded us that anyone of a dozen minor screw-ups—a lost key, a punctured fuel tank, a flat battery—could be disagreeably fatal. I failed to mention that we had already locked the keys in the car and survived.

In fact, the sum total of damage to our vehicles was one punctured tire, a pretzeled Hella mount (my fault), an immovable front seat whose track was jammed by a Diet Pepsi can (Berg's fault), floor mats stained red by the sand, and a sardine-juice spill (Hussey's fault) that will identify this vehicle as ours, probably in perpetuity.

Some men climb mountains because. They’re there. Some men drive to lonely spots because they're nowhere.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos