Those Who Brave the Greatest Tarmac Rally on Earth

It turns out there is an Irish word for walking a mile up a hilly road before standing in marshy ground for an hour in the rain. According to a fellow spectator, we’re enjoying the craic—pronounced “crack”—a catchall term for shared fun, camaraderie, or an unlikely adventure. It can be applied to everything from an evening in the pub to trading jokes over a gate or, as today, hiking through drizzle to the most scenic vantage point in European motorsport, overlooking a hairpin with a commanding view of the Atlantic far below.

This story originally appeared in Volume 19 of Road & Track.

This is the Donegal International Rally’s Knockalla stage, the most famous part of the Emerald Isle’s premier tarmac rally. Ireland is short on the forest dirt roads commonly used for rallying across the world, so most competition is on temporarily closed asphalt public roads. This provides an obvious parallel to the hugely popular motorcycle road racing in Northern Ireland. But the passion for tarmac rallying is widespread throughout the island, with events on tight, twisty lanes often barely wider than the cars themselves. Other European countries have asphalt rallies, but none love them more than Ireland. Rally Donegal is the only round of the Irish Tarmac Rally Championship held over three days, with a packed entry list of 163 cars this year. It brings thousands of spectators.

Several hundred hardy fans have braved the rain to watch the Knockalla above the beautiful Ballymastocker Bay. Far below, three sets of numbers and initials have been carved into the sand: MK#1, CB#42, and KB#43, in tribute to three former competitors. Three-time winner Manus Kelly was killed in a crash at the event four years ago. Craig Breen was a keen Irish amateur whose talent took him to a Hyundai works WRC drive before he died in a testing accident earlier this year. And KB is the late Ken Block, who once entered Donegal in his Ford Escort Cosworth, crashing out on the first day.

For the most part, the crowd at Knockalla waits patiently in the rain. “When are they going to throw some feckin’ cars up this feckin’ mountain?” asks a cynic, his appreciation of the craic slipping. Most shelter under raincoats and umbrellas, or, in the case of one hungover-looking group of lads, garbage bags with crude holes punched out for head and arms. Yet when the front-runners arrive, the crowd’s reaction is muted. The top order are in all-wheel-drive R5-spec modern rally cars, just one rung down from WRC challengers. They are hugely fast, reaching the hairpin with squealing brakes and rumbling anti-lag, accelerating out with barely a hint of oversteer. But drama is lacking.

Not, however, for long. An angrier, higher-pitched exhaust tone rouses the crowd as a boxy car appears in the distance. It takes longer to climb the hill to the corner, with its engine note rising and falling as a single axle fights for traction against the greasy surface. But by the time the car reaches the hairpin, spectators are leaning forward, and a phalanx of phones reaches out to record the moment. The first Mk2 Escort on the stage goes sideways well before the apex and well after it, fishtailing up the road to widespread exaltation. Great craic, indeed.

The second-generation Ford Escort is an unlikely star. Introduced to Europe in January 1975, the Mk2 quickly became part of the continent’s automotive wallpaper. The rallying version of this drab commuter debuted just five months later, when the Escort RS1800, fitted with a Cosworth-developed BDA engine, won its first event, the Granite City Rally in Aberdeen, Scotland.

Many victories followed. The Mk2 won no fewer than 20 WRC rounds over six years, carrying both Björn Waldegård and Ari Vatanen to their drivers’ championships. Alas, when rallying moved to its much more spectacular Group B era, the rear-driven, naturally aspirated Escort was eclipsed. But not forgotten—the basic car’s cheapness and commonality meant it remained hugely popular with amateur drivers.

Even as the parts supply and surviving chassis dwindled, the Escort wasn’t replaced. Permissive regulations allow Mk2s to compete against modern homologated machinery in series like the Irish Tarmac Championship using anachronistic modifications like sequential gearboxes and bespoke engines. Some drivers rally updated versions of other old cars; there were several impressively fast rear-drive Toyota Starlets in Donegal. But the Escort is king. Nearly a third of the rally’s starters were in Mk2 Escorts.

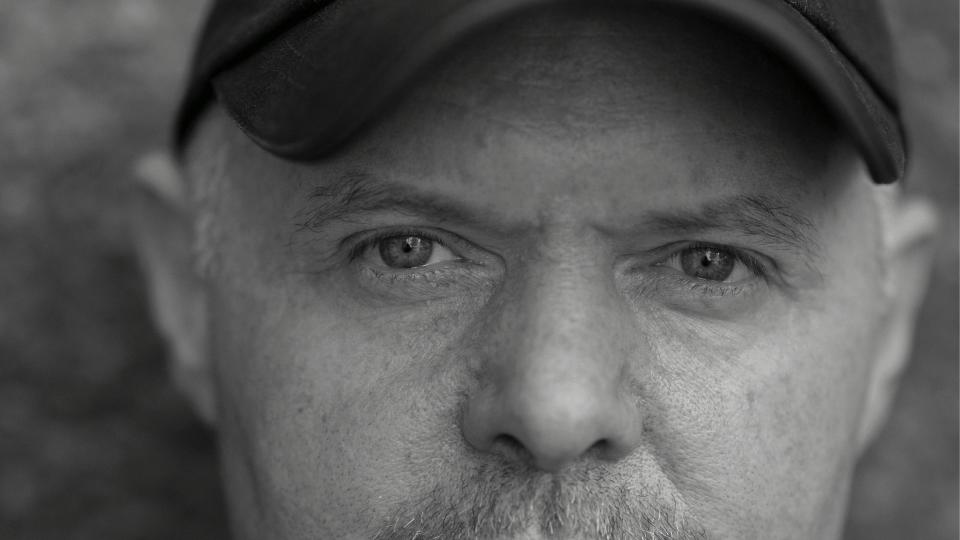

No modern Mk2 is better known than the bright-blue example belonging to Frank Kelly. If you’ve watched automotive videos online, the algorithm may well have already introduced you to Baby Blue. If not, take a few minutes on YouTube to acquaint yourself with Frank Kelly: Fast, Sideways and Mental, which more than delivers on the title’s promise. Kelly is competing in Donegal—he lives just across the border that separates this corner of the Irish Republic from the U.K. province of Northern Ireland—so he seems the perfect man to talk to about tarmac rallying and Ireland’s love for the Ford Escort.

“I’ve often had people ask me, ‘Did they stop building rally cars in 1980? What’s the story?’” Kelly says, standing next to his car. “I always say, ‘They stopped making good ones, yes.’”

Kelly’s attachment is partly emotional. Born in 1965, he grew up with rallying Escorts. But there’s a practical side to his affection.

“You can work on them in your shed, and it’s cheap to make them handle,” he explains. “In the early Noughties, it got hard to get parts for them, but then a new industry sprang up around them. You can get reproduction shells, panels, lights. You can literally buy everything you need for a new car and build it to your spec. These days, [Escorts] make much more sense than most other stuff.”

Sitting on high-lift stands, Kelly’s Baby Blue is a smorgasbord of high-end parts. The car is beautiful, its underside as clean as its bodywork. Renowned U.K. specialist Millington built the engine, which is, in essence, bespoke for rally racing, making far more power than any original works engines ever did. Kelly says his Millington mill produces 360 hp from 2.5 liters and is designed to last 1000 stage miles between rebuilds—a long interval given that Donegal’s three days consist of just 174 competition miles. It also has a Samsonas six-speed sequential transmission and a rear axle suspended by bespoke trailing arms and a Watts linkage; the original road-spec Mk2 Escort had just a pair of elliptical springs.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos