Toyota Is Right: We Need More Hybrid Cars and Fewer EVs. Here's Why

Once upon a time, Toyota led the mainstream push into energy-efficient cars with the hybrid Prius. Today, it’s seemingly more conservative, having pooh-poohed battery-electric vehicles for years in favor of things like hybrids and hydrogen—only to finally embrace EVs’ potential with the BZ4X. A little, anyway; it still firmly believes in a full spectrum of decarbonization solutions, one where hybrids are more important than full EVs.

It sounds like heel-dragging from a latecomer whose first electric car was met with a lukewarm reception. But if you take a closer look at how efficiently hybrids and EVs use their batteries, you’ll realize Toyota is actually right: hybrids have a bigger role to play in decarbonization than EVs will for a long time, if ever. Fact is, we need to use our limited battery supplies to deliver the maximum reduction in CO2 emissions across the auto industry, and soon. We need to use every last kilowatt-hour to its fullest, and in the near-term, that doesn’t mean going all-in on EVs. It means leaning back into hybrids.

The data is conclusive: Electric vehicles generate fewer carbon emissions than those powered by combustion engines over their lifetimes, and what you’re about to read doesn’t dispute that. But EV adoption is tripping over range limitations, patchy charging networks, and high prices resulting from the cost of the batteries that power them.

What’s more, EV battery supplies are expected to fall short of demand within the next couple of years. Benchmark Mineral Intelligence told The Financial Times it forecasts lithium demand growing fivefold by 2035, while Boston Consulting Group predicts “chronic” shortages as soon as 2025. Last year, Stellantis CEO Carlos Tavares warned of similar in CNBC, foretelling mineral and battery shortages later this decade.

So is there a better use for the batteries currently being crammed into a relatively small number of $60,000 electric sedans or $100,000 electric pickups? Could switching to full-hybrid model lineups—now mostly dismissed as a temporary bridge—actually reduce emissions quicker than fast-tracking EVs in the short term?

The Case for Hybrids Over EVs

To illustrate, we're going to compare the on-road carbon emissions of a few models that are available with internal combustion, hybrid/plug-in hybrid (PHEV), and electric powertrains: the Ford F-150, the 2022 Hyundai Kona and Kia Niro (which use the same chassis) and the BMW 3 Series and i4 (which also share their bones). Again, this is the question we want to answer: What’s the best use of a limited battery supply? Do we spread those materials across a bunch of hybrids, or cram them into a few EVs and leave the remainder with straight gas or diesel engines?

We can answer this by dividing how much each vehicle reduces CO2 emissions over its ICE counterpart by its battery capacity in kilowatt-hours. That’s tricky to imagine, so don’t bother: just look at this equation instead.

We need more data to fill that out, of course, and obtaining it is simple: The EPA’s FuelEconomy.gov publishes per-mile CO2 estimates, which also estimate the upstream emissions that come from gasoline production.

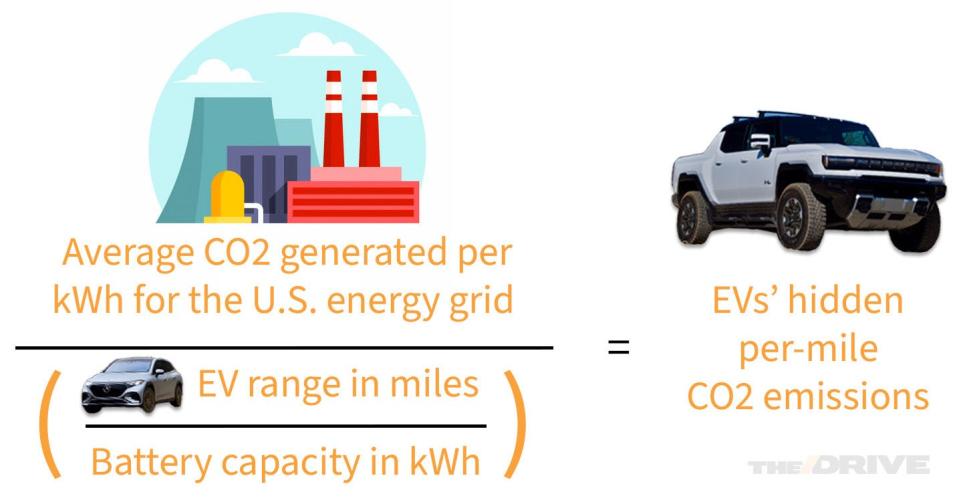

Things aren’t as straightforward for EVs, though, which the EPA lists as emitting no CO2. While true from an exhaust standpoint, making the electricity needed to charge them does generate CO2: an average of 386 grams of it per kWh in the United States, according to the Energy Information Administration. We can then estimate their hidden CO2 emissions with the equation illustrated below. (It’s the same formula we used to calculate the break-even point for EVs when it comes to charging and production emissions vs their on-road savings last year.)

Armed with this data, we can then calculate how efficiently each electrified vehicle uses its battery. The equation we’ll use for that is shown above—remember, the goal is to reduce CO2 emissions as much as possible with a limited supply of batteries. And when you do the math, it’s pretty clear what the best option is.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos