As Turbocharging Takes Over, Some Types of Vehicles Stand to Lose More Than Others

From the June 2018 issue

Progress is rarely victimless. The cotton gin mangles limbs. Robots take jobs. The internet kills common decency.

Even if the tidal shift toward turbocharged engines promises quicker and more efficient vehicles, it will come at some cost. To weigh the price and payoff of turbocharging, we slapped our test gear onto two pairs of naturally aspirated and boosted vehicles. The first matchup situates the modern turbocharging skirmish inside a battle that has raged for more than half a century.

Ford Mustang vs. Chevrolet Camaro

Ford’s 310-hp turbocharged 2.3-liter inline-four killed off the Mustang’s naturally aspirated V-6 engine in the 2018 model-year refresh. Chevy sells a turbo-four pony, too, but the Camaro’s 2.0-liter is significantly less powerful at 272 horses, and frankly, it’s impossible to say nice things about that coarse and overburdened lump. Instead, Chevy enters the Camaro’s 335-hp naturally aspirated 3.6-liter V-6 into the same fighting class as Ford’s turbocharged four-cylinder.

On numbers alone, this is practically a dead heat. The lighter and more powerful Camaro rushes to 60 mph in 4.9 seconds and completes the quarter-mile in 13.6. Packing a 66-lb-ft torque advantage, the Mustang trails by just 0.2 and 0.1 second, respectively. These engines—and the cars wrapped around them—aren’t as similar as the numbers suggest, though, because the difference between the blown Mustang and the free-breathing Camaro can’t be measured in tenths of a second.

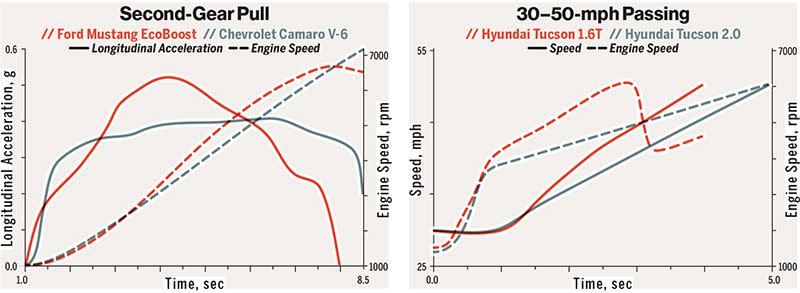

To understand how pressure charging changes a car’s character, you have to feel how these two engines rev and accelerate. The first chart at the bottom of the page quantifies the sensations as best we can with second-gear pulls from 1000 rpm to redline. The Camaro’s nearly flat longitudinal acceleration plots the unyielding intensity that’s uncorked within moments of flexing your right ankle. The arrow-straight ascent of the engine’s revs captures the spectacular linearity of this 3.6-liter climbing to the fuel cutoff, where arriving at 7200 rpm feels practically exotic in the era of modern turbocharged engines that often tap out around 6000 rpm.

The Mustang revs quicker once the turbo spools and ultimately pulls harder in second gear as it briefly peaks above 0.5 g of straight-line acceleration. But that advantage is just a momentary thrill. The turbocharged yank swells and retreats, a passing wave that can’t be captured. The upswing at the low end conveys growing urgency as boost builds. Soon after, though, the engine starts to choke like a sprinter gasping for air halfway through a race. Spinning the engine into the top third of the tachometer, you’re often left wondering if you should have shifted sooner. And the dull exhaust note only adds to a general lack of drama. We know this engine can display a bigger personality than it does in the Mustang. The 350-hp version in the Focus RS bristles and charges as if it’s running on Red Bull.

Chevrolet’s V-6 has clearly been taking voice lessons from the Camaro SS’s small-block V-8. Helped by an active exhaust, it lets out a 91-dBA yowl at full throttle, a bellicose challenge to creeping conformity. This engine, one of the last great unboosted sixes around, is proof that turbocharging cuts both ways, particularly when it replaces cylinders in sports cars where subjective traits carry greater significance.

Hyundai Tucson vs. Hyundai Tucson

It’s a different story in the many affordable mass-market segments where turbocharged four-cylinders increasingly supplant breathy and gutless naturally aspirated fours. While many automakers have already picked turbocharging as the winner, a handful of model lines leave the decision to buyers, offering a smaller turbocharged four-cylinder as an extra-cost upgrade over the base unblown engine or with higher trim levels. These boosted engines typically deliver a trivial advantage in peak power but bring a small nudge on the EPA fuel-economy label and a big bump to low-end torque. You can sample this automotive Pepsi Challenge in vehicles such as the Ford Escape, the Honda CR-V and Civic, and the Hyundai Tucson, which we drafted for this test.

Hyundai’s compact crossover starts at $23,530 with a 164-hp naturally aspirated 2.0-liter inline-four. Spend another $4000 for the Value trim (irony comes standard) and you’ll step up to a 175-hp turbocharged 1.6-liter inline-four. The turbo Tucson returns performance that far outstrips its 11-hp edge and more than makes up for its considerable 210-pound weight penalty. The naturally aspirated model ambles to 60 mph in 9.6 seconds and begs for mechanical sympathy with a distressed groan that’s four decibels higher than the relatively muted turbo engine. At 7.3 seconds to 60 mph, the turbocharged Tucson is legitimately spry.

How is such a large margin possible? The blown Tucson spreads its torque on both sides of the bread, covering 1500 to 4500 rpm with 195 pound-feet. The unboosted 2.0-liter engine musters only 151 pound-feet—and not until it has labored to 4000 rpm. The turbo’s torque delivery pays off in the real world, where it accelerates away from traffic lights with more authority, fewer revs, and less audible strain.

You can see it in our 30-to-50-mph passing-maneuver test, as shown in the chart on the right below. Starting from a 30-mph cruise, with both engines turning a neat 1500 rpm, we pin the throttle pedals to the firewalls. The turbo engine’s seven-speed dual-clutch transmission and the 2.0-liter’s conventional six-speed automatic react with near identical response times. Both grab second gear, and revs surge to roughly 4000 rpm. And then the turbocharged Tucson, helped by shorter gearing, walks away from its naturally aspirated twin, completing the maneuver a full second quicker than the 2.0-liter model.

These Tucsons tell the story of the broader automotive market. Turbochargers are making vehicles objectively better for the masses. It’s not so simple for performance cars and enthusiast specials, though. Naturally aspirated engines are facing the same fate as manual transmissions and rear-wheel-drive dynamics, and the consequences are just as unfortunate. As free-breathing engines are squeezed out of the market, we’re breaking connections to the mechanical world—the unfiltered fury of combustion, the sustained squeeze of linear acceleration, the adrenaline spike of a tachometer notching 7000, 8000, and 9000 rpm. We’re trading emotion for quickness. We’re trading what we can feel for what we can measure. That’s the price of progress.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos