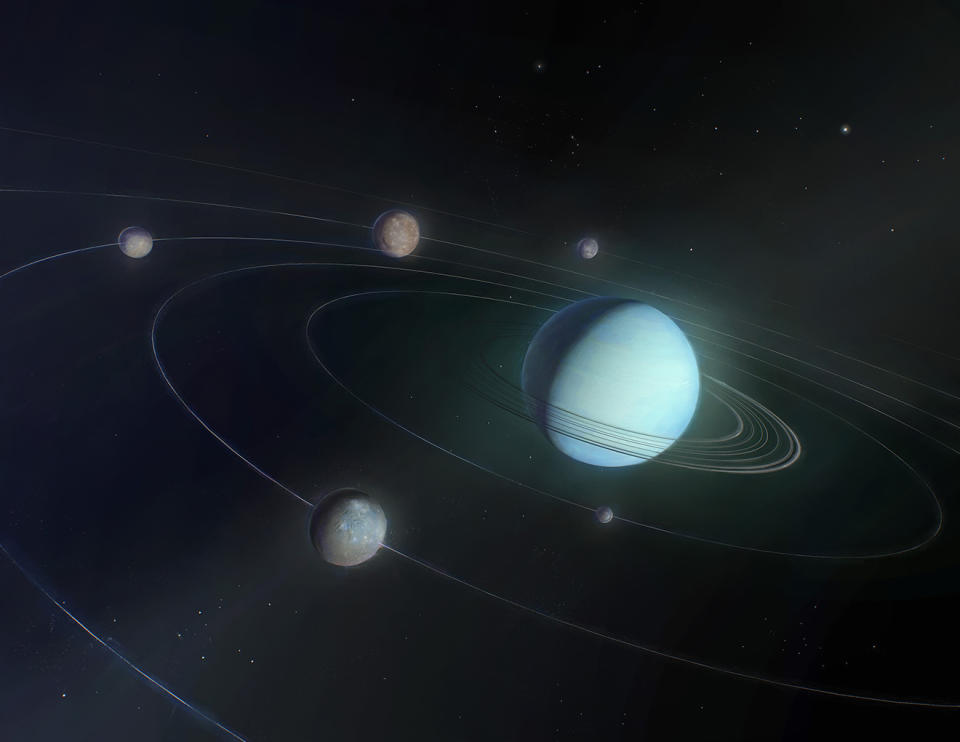

Two moons of Uranus may have active subsurface oceans

Two of Uranus' moons may have active oceans that are pumping material into space, a new study finds.

The realization that there may be more happening in the Uranus system than previously believed came via the discovery of strange features in radiation data collected by NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft as it passed the planet almost four decades ago.

The new findings, concerning the moons Ariel and Miranda, also support the idea that Uranus' five largest satellites could have subsurface oceans, a notion suggested by Voyager 2 flyby observations.

Related: Photos of Uranus, the tilted giant planet

The study team examined radiation and magnetic data collected by the spacecraft in 1986, long before it made its way out of the solar system.

The newly reported observations of Voyager 2 — currently the only spacecraft to have visited Uranus — showed that one or two of the ice giant's 27 known moons are adding plasma particles into the Uranus system. This detection came in the form of "trapped" energetic particles the spacecraft spotted as it departed the ice giant.

The mechanism by which Miranda and/or Ariel may be doing this is currently unknown, but there is one very tantalizing possible cause: One or both of the icy moons may possess a liquid ocean beneath their frozen surface that's actively blasting plumes of material into space.

Similar particle-releasing moons exist around Uranus' fellow solar system ice giant Neptune and the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn. In the case of the Jupiter moon Europa and Saturn's Enceladus, it was the examination of particle and magnetic field data that provided the first hints that these are ocean moons.

"It isn't uncommon that energetic particle measurements are a forerunner to discovering an ocean world," study lead author Ian Cohen, a space scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, said in a statement.

"We've been making this case for a few years now, that energetic particle and electromagnetic field measurements are important not just for understanding the space environment but also for contributing to the grander planetary science investigation," Cohen added. "Turns out that can even be the case for data that are older than I am. It just goes to show how valuable it can be to go to a system and explore it first-hand."

Related: Why scientists want NASA to send a flagship mission to Uranus

Another look at Uranus and its moons

The findings will only strengthen the desire of planetary scientists to send spacecraft back to Uranus and Neptune to collect more data, which led to the suggestion of a $4.2 billion flagship mission to Uranus as NASA's next major planetary mission.

This mission wouldn't be ready to launch until the early 2030s, so in the meantime, researchers have been diving back into old data collected during the Voyager 2 flyby to make new discoveries.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos