I’ve Been to the Mountaintop

Rise and fall on a racetrack is the difference between a merely challenging layout and an unforgettable one. Elevation change creates drama by its nature, upsetting a race car in spectacular ways; blind summits and plunging toboggan-sled sections reward bravery and commitment. For the crowd, the sight of a car appearing at full noise, teetering on the edge of flight or trailing sparks into a compression, is oddly physical. You feel the energy of the car, the attitude, the struggle.

This story originally appeared in Volume 19 of Road & Track.

Just outside the town of Bathurst, New South Wales, in eastern Australia, the Mount Panorama circuit embodies these qualities completely. As a bonus, the mainstay competition cars in this part of the world are big, relatively heavy V-8-powered sedans and coupes. Together, the circuit and the cars create a unique set of circumstances. The headline event, the Bathurst 1000, is glorious drama played out over 1000 km in front of a crowd thirsty for intense battle and even thirstier for a party. Legend has it that when the authorities introduced a limit to the amount of alcohol each fan could bring to the Bathurst 1000, some circumvented the restrictions by burying extra supplies in the surrounding hills before the race weekend. Incidentally, the limit is set at 24 cans per person per day. Like I said, thirsty.

Don’t imagine our beer-sodden heroes cutting through barbed-wire fences to stash their loot, though. There’s no need. Mount Panorama is a street circuit. On any given Monday, you can simply drive onto the track and take a slow tour. The speed limit is 37 mph (60 km/h), and it’s a two-way road. There’s no central line, just painted saw-toothed curbs and advertising billboards. This street circuit offers an experience quite unlike any other. The weird abandoned-yet-pristine-racetrack ambience is down to Mount Panorama’s fascinating history. Suffice to say, its founders were as tricky as those beer-burying fans.

Back in the Thirties, government funding for a permanent racetrack wasn’t easy to come by. So Bathurst mayor Martin Griffin instead accessed a Depression-era national employment-relief scheme by creating a road project. Touring the place the local Wiradjuri people know as Wahluu (meaning “to watch over”), he called the road the Mount Panorama Scenic Drive. It opened on March 17, 1938. One month later, the Scenic Drive held its first race. Griffin’s brainchild was a loophole-exploiting masterstroke, combining ingenuity and extreme topography to create one of the world’s truly great racing circuits.

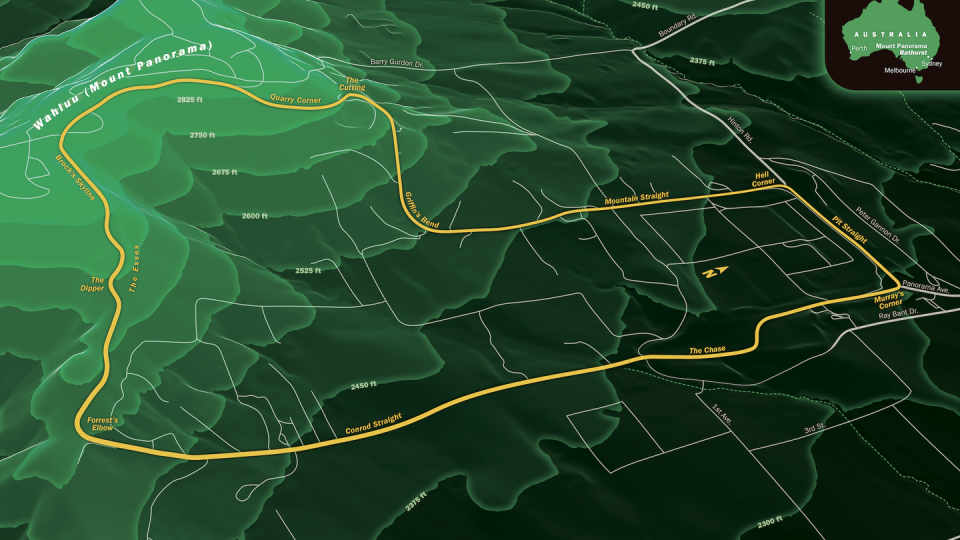

The landmark names are so good, so evocative: the Conrod Straight, Hell Corner, Brock’s Skyline, the Cutting, Frog Hollow, the Dipper. Read them aloud and you instinctively adopt an Australian accent. Mount Panorama has a rawness—a kind of straightforward, no-bullshit, all-action vibe—that matches its hammering big-cube soundtrack. It’s peculiarly and wonderfully Australian.

There’s a sense of untamed lunacy that’s impossible not to love. Watch grainy old footage of Tom Walkinshaw in a screaming TWR Jaguar XJ-S tackling the Mount, Peter Brock bouncing over curbs with an armful of opposite lock in a Holden Commodore, or Mark Skaife in a fire-belching Nissan Skyline GT-R, and the intensity is plain to see. This place has an ugly side too. Pitched battles between police and spectators during the Easter motorcycle races, cars set ablaze in the campsites, and frequent skirmishes plagued Bathurst in the late Seventies and early Eighties. It’s more orderly now, but past lawlessness gives depth to the fascinating lore around Mount Panorama.

Arriving at this sometime battlefield on a quiet Tuesday morning is surreal, the warm air still as can be and the only sounds birdsong and the chatter of insects. To get there, follow Panorama Avenue south from the town of Bathurst for about five minutes, and you’ll stumble across the track. There’s a small museum and gift shop on your left, but you can worry about that later. For now, just keep driving and enter the Scenic Drive on Murray’s Corner, which links the vast, rolling Conrod Straight to the shorter Pit Straight. Turn right, and you’re following in the tire tracks of legends such as Peter Brock, a local hero and unprecedented nine-time winner of the 1000. Pass under a luridly sponsored footbridge, past race control and the pit complex, and you’ll come to the Hell Corner left-hander. This is where the climb begins.

The Mount Panorama circuit is 3.861 miles long, and the difference between its lowest and highest points is 571 feet. It has gradients up to 1:6.13 (13 percent). At the permitted 37 mph, a complete lap takes a leisurely 6 minutes, 16 seconds, and every single moment is a thrill—admittedly not the sort enjoyed by outright lap-record holder Christopher Mies when he flung his Audi R8 LMS Ultra GT3 car around the track in 1:59.29 back in 2018. Yet there’s something strange about rolling onto a public road that’s very clearly just a racetrack. The Scenic Drive doesn’t really lead anywhere except back to the Pit Straight. There are about 40 houses, a winery, a gun club, and a couple of hotels tucked away down small feeder roads, but this is not Casino Square in Monaco. The ultimate blood-and-thunder racetrack is oddly calm for about 90 percent of the year.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos