How VTEC Changed the World

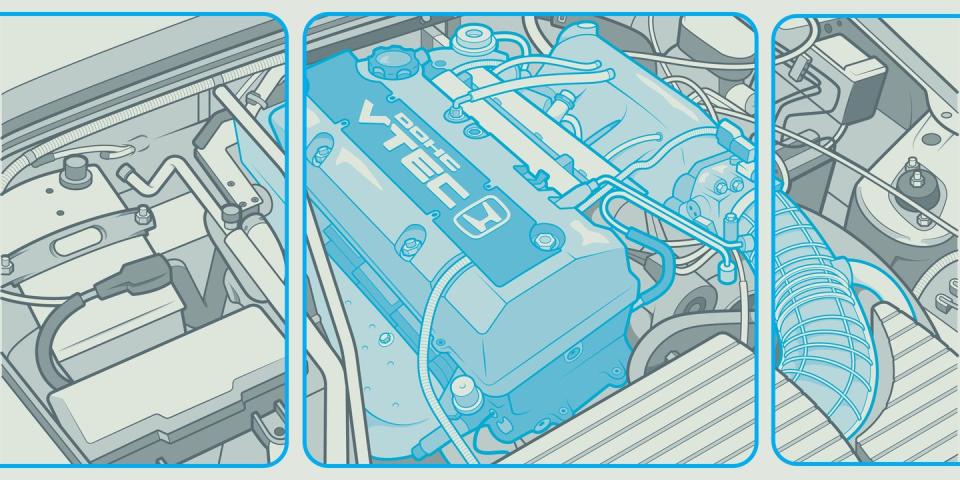

Honda did not invent variable valve timing or variable valve lift. In fact, Cadillac had a driver-operated variable valve timing system in production in 1903, three years before Soichiro Honda was born. Alfa Romeo and Nissan also had variable valve timing in the Eighties, but it was the 1989 Integra and its 1.6-liter VTEC four-cylinder that created a legend.

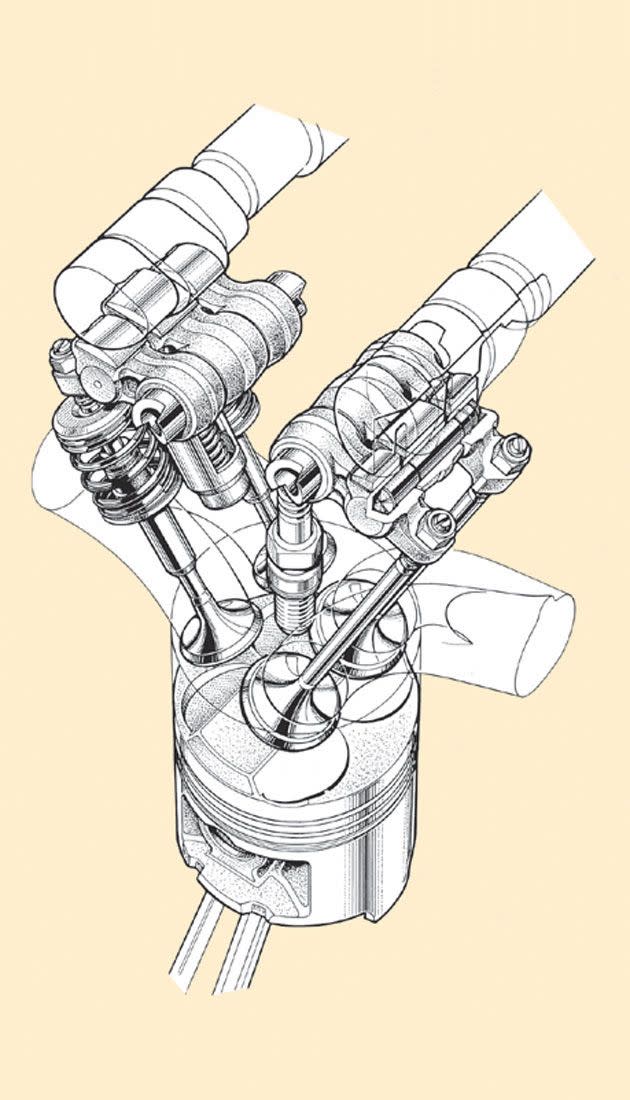

So much of automotive engineering is about minimizing compromise, and doing so while also minimizing cost. With a conventional valvetrain, valve lift (how much the valve opens), valve timing (when the valve opens), and duration (how long it opens) is defined by the camshaft profile, the shape of the individual cam lobes on the shaft. Before variable valve timing and lift, auto engineers had to select a cam profile that provided a desirable compromise between performance and efficiency across a wide powerband. Engines want different things depending on load and operating speed. A camshaft profile that gives you good fuel economy when puttering around town isn't optimal when you're wide-open-throttle at high revs. By changing valve timing, duration, and lift, you can optimize for all sorts of different running conditions. The trick is to do it reliably and cheaply.

The benefits of such a system were obvious even to the first automotive engineers. At the 1989 SAE international congress, a pair of Stanford professors presented a paper which noted that at least 800 patents around variable valve timing had been granted since 1880. By examining these patents, the researchers created 15 classifications for different variable valve timing systems, but concluded "VVT has much potential, but that very little of this potential has yet been realized. Serious difficulties have limited the application of variable valve timing to date. Virtually all VVT mechanisms proposed until recently suffer from high cost and complexity, limited variability, and high impact velocities."

That very next SAE paper was written by three Honda engineers, detailing a prototype VTEC system as fit to a 1.2-liter DOHC engine. It is the classic VTEC system as we know it today, with two low-speed cams on either side of a high-speed cam. The two low-speed cam profiles operate as normally at lower engine speeds, acting on rocker arms that press on the valve stems. The third cam profile is essentially freewheeling at this point, acting on a separate rocker arm not attached to the two acting on the valve. At a certain engine speed, the ECU triggers a solenoid, which opens an oil passage that forces a piston to lock the three rocker arms together. Now, the larger cam profile is at work, increasing valve lift and duration.

This paper may have described a prototype system, but just two months later, VTEC made its debut in the second-generation Integra. (The U.S. would have to wait two years for the launch of the NSX to get its first VTEC engine.) The engine was a marvel. Initially, the target for the new Integra's was 140 horsepower from a 1.6-liter, but that was just 10 better than its predecessor. According to a history from Honda, Ikuo Kajitani, the engineer in charge of Honda's four-valve engines, didn't think this was enough for a car entering a new decade. Honda R&D chief Nobuhiko Kawamoto suggested that Kajitani aim for something that seemed illusive among naturally aspirated engines—100 horsepower per liter. Absent an increase in displacement—undesirable for the Japanese market—that sort of power meant more revs. Eight-thousand to be exact, well into racing territory, and far higher than any other mass-market four-cylinder of the time. Hitting that number while also achieving good fuel economy and drivability around town would require more flexibility from the valvetrain. VTEC was the obvious solution, if not the simple one.

Work on the engine, the B16A, started in 1986, so there wasn't a ton of time to get it into production. Its high-revving nature also meant materials selection was a huge challenge, as parts needed to be both lightweight and strong, thus expensive. The abbreviated timeline also meant engineers needed to be militant about which components were necessary and which weren't for making the VTEC system work, and work reliably. When all was said and done, the 1989 Integra XSi offered 160 metric horsepower (152 of our imperial horsepower) at 7600 rpm.

In R&T's August 1989 issue, Japan Editor Jack Yamaguchi noted that the engine was expensive, adding around 15 percent of cost compared with the 1.6-liter SOHC Integra. The forged and polished crankshaft apparently had more than a passing resemblance to the company's F1 cranks. This was Japan's price-asset Bubble Era, when money seemed to be endless and automakers flexed their engineering muscles to create some of the greatest cars of the modern era. An 8000-rpm twin-cam four in a sporty mass-market hatchback seems batty now, but just look at the other Japanese cars of the era. This is when Toyota went after Mercedes, when Nissan tore apart a Porsche 959 to develop an all-wheel drive super coupe, when Mazda decided to single handedly revive the roadster. On-the-limit technology was allowed to proliferate, so why not put an engine with more power per liter than the ultra-specialized E30 M3 into what was essentially a fancy Civic?

Yamaguchi declared the B16A "sweetest power unit the house of Honda has ever put on four wheels," and promptly ordered an Integra XSi. Honda president Tadashi Kume was so impressed by VTEC, he ordered the V-6 in development for the NSX be reengineered to accommodate the system. It was an expensive endeavor that came late in the car's production, but one that gave Honda's supercar power to match the Ferrari 328 with two fewer cylinders.

"A lot of the engine guys came from our F1 program," Kurt Antonious, Honda's longtime PR lead, remembers of the early VTEC days. "They learned so much in F1 racing as far as getting the most performance, you know, with the least amount of weight in the engine." Honda's culture was conducive to fostering such a technology, too. Then, as now, it is a company made in Soichiro Honda's image, and Mr. Honda was an engineer first and foremost. Antonious points out that in the late eighties and early nineties, R&D received huge investment, creating what he considers a "magical era" for the company.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos