Scandal over government handling of World War I surplus

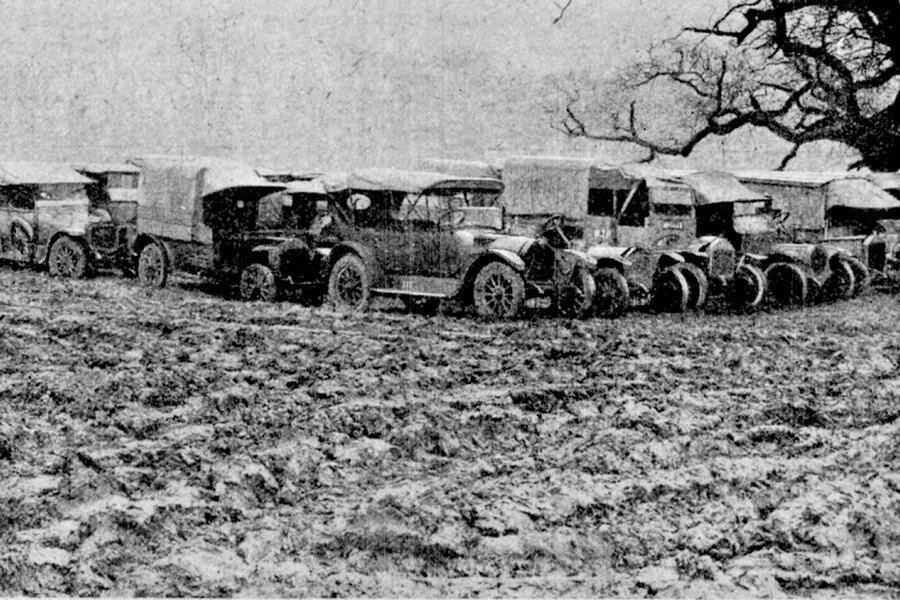

Brits flocked to buy ex-army cars - once they had been freed from the mud

“Those who have passed through the station at Sunbury [in Surrey] by train have obtained a glimpse of an immense area literally covered with cars, lorries and motor bicycles exposed to the weather,” we reported in January 1919. “The public naturally asks: why is the nation’s property neglected in this manner?”

The “lamentable waste of public money, owing to neglect due to lack of foresight and organisation” that they had seen at Kempton Park was one of Britain’s many newly redundant armed forces depots.

Around 7000 cars were awaiting their fates there, from the War Office’s total of about 12,000.

There was actually plenty of demand for them, but anyone interested first had to obtain a special permit, travel to Sunbury, “wade through mud and mire” to reach the mostly dilapidated and damaged cars – and then not even be allowed to test if they worked.

Enjoy full access to the complete Autocar archive at themagazineshop.com

The Motor Cycle magazine was likewise angered by the wastage, even though “the majority will require a great amount of work before they are fit for the road”, many of them having been run over, shelled or even buried for months in Flanders battlefields.

At the same time, we worried that a sudden flooding of the used market would seriously hamper the British car industry’s efforts to transition back from war work.

A re-elected coalition led by David Lloyd George had formed the Surplus Government Property Disposal Board under the Ministry of Munitions to recoup some of the huge costs of the war (which the UK didn’t pay off until 2015!), but clearly things hadn’t started well.

Promising signs on the vehicle side were first seen in March, as Autocar reported on an auction of record size in Islington, London, where 104 cars and 200 motorbikes were trucked in from Sunbury and sold. And in the autumn, we ran ads for weekly vehicle auctions at the Earl’s Court Exhibition Centre.

Soon after, the board struck a £7 million deal (£261m in our money) for its vast Slough depot, which had been damned by a parliamentary inquiry as outrageously wasteful.

The buyer was a consortium led by Percival Perry, Ford of Britain’s visionary ex-boss. After profiting from the 15,000 vehicles there, the group persuaded new French car maker Citroën to build a factory in Slough, and the resulting trading estate became a roaring success. Let’s be kind and assume the board being busy finalising this deal was why three times it failed to acknowledge another firm’s offer to buy as many as 3000 lorries!

It’s little wonder that the board struggled to keep up when you see this ad it placed in the Evening Mail: “Government property for sale. Factories, aerodromes, huts, building material, furniture, domestic equipment, machinery, power plant, steam plant, electric plant, agricultural machinery, road bridges, railway material, dock equipment, contractors’ stores, textile goods, clothing, boots and shoes, medical stores, machine tools, chemicals and explosives, river and canal craft, motor launches and steamers, general stores, etc, etc.”

Also in 1920, a massive deal was done for 10,000 aircraft and 33,000 aero engines, with the new Aircraft Disposal Company paying £100m. It would take a decade to sell all of that.

Yet even while the board trumpeted bulk sales of a million yards of balloon fabric, 4.7 million yards of serge and tartan, mountains of condensed milk and more, the Daily Mail was reporting on a Nottingham munitions dump: “The accumulation of material is so immense that much of it has been left to rot in the open. We are told of thousands of wheels; tens of thousands of wagons and carts; of millions of rusting horseshoes; of saddles innumerable; of barbed wire sufficient to enclose these islands; of clothing items by the million; of tents and entrenching tools and building materials.”

What a terrible waste – as if the lives of a million young British men hadn’t been enough.

The board finally finished its work in March 1924, having handled some 5,000,000 tons of material and made back £665m (that’s £33.8bn to us) – a good deal of that from abroad, mostly badly war-torn France and Belgium.

]]>

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos