Here Are Some Weird Things You Probably Didn't Know About The Porsche 911

There is no car on sale that’s like Porsche’s long-lived and much-lauded 911. Partly that’s because it’s the only car you can buy new today in the US with a rear-mounted internal combustion engine but also, very few cars have had the continuous, incremental improvement that the 911 has over the decades.

While that evolution-not-revolution approach has made the neun-elfer one of the world’s most competent and beloved sports cars, it’s also introduced more than a few quirks and design oddities, many of which you’d only know about if you were a colossal nerd, or if you owned one.

Read more

‘All Of Sony Systems’ Allegedly Hacked By New Ransomware Group

R.I.P. David McCallum, NCIS and The Man From U.N.C.L.E. actor

The Creator is next-level sci-fi. So why isn't it being promoted that way?

Because the 911's engine is in the back of the car, the gas tank has to go in the front (well, front middle) and something about the angle of the filler or the design of the fuel neck of my 996 (and I suspect the 997 as well) means that in states that use California-style gas pump nozzles with the vapor capture accordion thing on it, the auto-shut-off feature won’t let you get more than around 3/4 of a tank. Weird and annoying, right?

The fix for this is either buy a little plastic thing that clips on the fill neck, or, if you’re cheap, turn the gas pump handle upside down. The auto-shut-off works correctly and you get a full tank.

Leaded Bumpers

911s have a reputation for being tough to drive fast, and while in many cases this isn’t totally justified, with the early “short wheelbase” cars built from 1964 through 1968, it certainly was.

To help calm things down for drivers, Porsche installed huge weights in the front bumpers of these cars with the idea that by putting more weight on the front, it could increase traction and reduce a driver’s tendency to lift off of the throttle during understeer (this is a really bad idea in an old 911).

Did it work? Kinda, but adding big lead or cast iron diving weights to a sports car isn’t ideal and so in 1969, Porsche extended the wheelbase of the 911, making for a much more stable car and obviating the need for the weights.

Targa Talk

Other"/>

The 911 Targa is an iconic design. Porsche even kept using the name even when the Targa roof itself fell out of favor (993, 996, 997 etc.) before bringing the Targa roof back in 2014 with mechanized operation but classic looks.

But why did Porsche go through the trouble of designing and building something like the Targa (named for the Targa Florio road race) when what people really wanted was a convertible?

As with so many things 911-based, it happened because of America. Porsche had heard rumblings that the US might outlaw convertible vehicles over safety concerns, and with the US being Porsche’s largest market, it decided to hedge its bets by creating an integrated roll bar — later to be known affectionately as the “basket handle.”

The first Targa models were known as soft-window Targas because the rear window was made of plastic and could be folded down, offering a much more convertible-like driving experience. That design lasted until 1969 when US regulations once again forced a change, this time to a fixed glass rear window.

The 911 Almost Didn’t Escape The 80s

While it’s hard now to imagine Porsche without first thinking of the 911, there was a time when the company’s executives were eager to kill it off. That sounds bananas, I know, but in the 1980s, Porsche was seeking to modernize. It wanted to make production more efficient, its cars easier to drive and more in line with growing trends and tightening regulations. The 911 still being a largely hand-assembled car on an ancient production line, with a clattery air-cooled engine and a reputation for nasty handling wasn’t helping any of this.

In 1981, Porsche’s boss Ernst Fuhrmann (developer of the 911 Turbo as well as the 934 and 935 race cars) was ousted after leading the company to its first year in the red financially, and he was replaced by American Peter Schutz (still the only American to hold the position).

As Schutz took charge, the writing for the 911 was literally on the wall, with the development timeline chart on Porsche Chief Engineer Helmuth Bott’s wall showing the 944 and 928 continuing on indefinitely, but the 911 stopped in 1981.

In his third week as CEO, Schutz visited Bott’s office and what happened there is now legendary.

Excerpted from an interview with Schutz by Road & Track before his death:

As far as the company was concerned, the 911 was history. But I overturned the board’s decision in my third week on the job. I remember the day quite well: I went down to the office of our lead engineer, Professor Helmuth Bott, to discuss plans for our upcoming model. I noticed a chart hanging on his wall that depicted the ongoing development trends of our top three lines: 911, 928, and 944. With the latter options, the graph showed a steady rise in production for years to come. But for the 911, the line stopped in 1981. I grabbed a marker off Professor Bott’s desk and extended the 911 line across the page, onto the wall, and out the door. When I came back, Bott stood there, grinning.

“Do we understand each other?” I asked. And with a nod, we did.

Just-In-Time

Other"/>

Today Porsche is a powerhouse that cranks out world-beating sports cars as well as EVs, SUVs and crossovers, but in the 90s it was losing money and dangerously close to being taken over by a rival company. A big part of this money-losing situation came down to the way that Porsche built its cars which, despite being devised by ze Chermans, was pretty inefficient.

To help solve this, Porsche attempted to do what no other German automaker had been able to do until that time, which was to adopt Japanese manufacturing principles in its factories. To make this happen, Porsche hired a consulting firm called Shingijutsu, which, coincidentally was founded by a bunch of ex-Toyota engineers, to make just-in-time manufacturing happen just in time for Porsche to keep its independence.

This major shift saw things changing in factories but also with the cars themselves. For example, the 996 911 and the 986 Boxster shared a front end, because if you have to make parts, why not get two models out of it? Ultimately, this made sense at the time, but Porsche obviously went on to differentiate the models again after getting criticism.

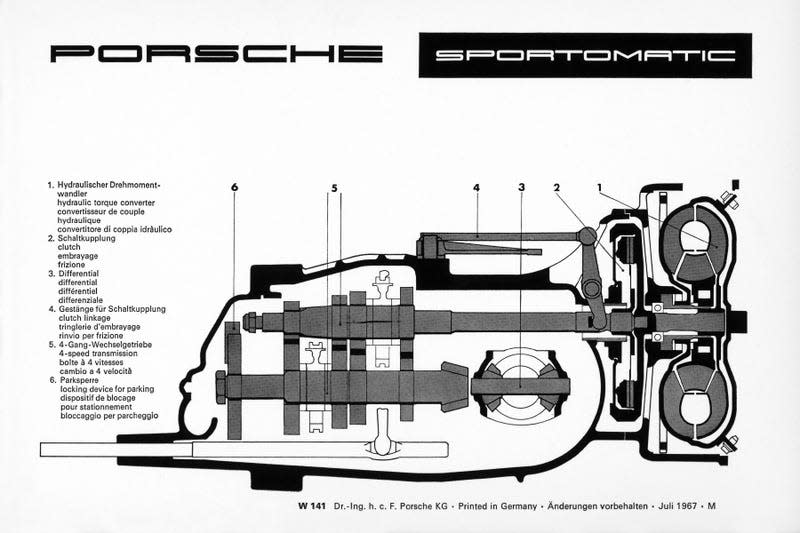

Porsche’s Sportomatic Gearbox

Most people who read Jalopnik will likely agree that a real sports car deserves a manual transmission. This is borne out by the fact that for decades, three pedals and a stick were the only way you could get many sports cars. Hell, the 911 didn’t get an automatic transmission until 1989!

Or, well, that’s mostly true. See, Porsche offered something called the “Sportomatic transmission” from 1967 to 1980 and it was something of a hybrid of a manual transmission and an automatic. They weren’t especially common, but they are pretty interesting. Volkswagen used a version, too.

When I say that the Sportomatic is a hybrid between a manual and a torque converter auto, what I mean is that you shift your gears manually (three or four of them, depending on the year) but you don’t have a clutch pedal. Instead of that pedal, the Sportomatic uses a torque converter to allow the car to come to a stop without stalling AND a conventional-ish clutch that is controlled pneumatically by microswitches on the shift lever.

Shifting works like this: You’re sitting at a light and the light turns green. You move the gear stick into first gear. When you touch the stick, the microswitch actuates a solenoid that actuates a pneumatic valve. This valve used vacuum to release the clutch allowing the synchros to work and shift into gear. Once you’re in gear and take your hand off of the gear stick, the clutch reengages and you’re off.

It gets cooler and also weirder. Instead of having 1, 2, 3 and 4 for gears, Porsche gave the Sportomatic L, D, D3 and D4. Low was like first gear in a normal manual, but Porsche said it was just for steep hills and encouraged drivers to set off in D. D and D3 were like shorter second and third gears in a standard transmission and D4 was overdrive.

The torque converter that allowed the car not to stall also acted as a torque multiplier which means that technically, you could set off in any of the four forward gears.

More from Jalopnik

Rick And Morty’s Season 7 Trailer Reveals New Voices Replacing Justin Roiland's

Community wasn’t funny enough for Chevy Chase, says Chevy Chase

You can stick a fork in these NFL teams, because they are done

Sign up for Jalopnik's Newsletter. For the latest news, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos