Welcome to the Clubhouse

NOTE: This article first appeared on autoweek.com 9/25/2015. Since the story ran, not only has Roger Penske purchased both the IndyCar series and the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, Team Penske has won two more Indy 500s. Penske's team won with driver Will Power in 2018 and driver Simon Pagenaud in 2019. Corvettes paced those two 500s, a ZR1 in 2018 and a Grand Sport in 2019. Since Penske can't show off to the fans all the improvements he has made to the speedway this year, we thought we'd honor him by re running this piece.

They are a Buick, two Chrysler products, five Chevrolets, two Fords, five Oldsmobiles and the Pontiac Fiero, all displayed in the same place for the first time. They are the Indianapolis 500 pace cars from each of Team Penske’s 16 Indianapolis 500 victories.

Some of these cars embody the diverse bits of awesomeness that make car enthusiasts car enthusiasts. Others leave you wondering what the people who created them were thinking. At least one of the 16 borders on ridiculous. The Indianapolis Star assembled a list of the 10 worst pace cars of all time before this year’s 500, and five of its choices reside in Penske’s collection.

What stands out more than any of the cars is the evolutionary span all 16 represent—from the tail end of the first muscle-car golden age through the onslaught of performance-choking emissions control, through several downsizing trends, the rebirth of performance, the personal-use truck and microchip revolutions and right up to the new golden age car enthusiasts enjoy today. Sixteen cars for 16 Indianapolis 500 wins spread through five-straight decades, by a team owner who wants to win the 17th as badly as he wanted the first.

Team Penske is frequently called the New York Yankees of motorsport, and that might be appropriate based on Roger Penske’s Indy wins—the next-most successful team owners have five—or on how long he’s stayed at the top of his game. The Yankees comparison doesn’t really say much about the breadth and depth of Penske’s motorsport endeavors, or the entrepreneurial brilliance of an owner who built a single Chevy dealership in Philadelphia, purchased just out of college, into a corporation that employs 48,000 people on five continents. It says nothing about a man who, according to associates working with him daily, never lets his ego get in the way of the right call.

Roger Penske must be a busy man, but there he sits under a tent next to his 16 pace cars, at the edge of Woodward Avenue, a bit north of Detroit. He’s decided to gather the cars in his hometown, with a 16-mile parade and as many of his winning drivers as he could get in one place, for the enjoyment of his guests and as many of the roughly 1 million Woodward Dream Cruise attendees who happen to stream by.

“The Dream Cruise is an iconic event, and this is a display of cars nobody else has,” says Penske, known widely to associates as The Captain, or just RP. “Certainly M1 (Woodward) is an iconic road, and we get a chance to take cars up and down it for two or three days when everyone is watching. No entry fee. Nobody has to pass inspection, and guess what? You can drive down Woodward for as many hours as you want. You can be in the race, and that’s something people just can’t believe when you talk about it in different parts of the country.

“I told someone (on the phone) that I’m taking my 16 pace cars and running them on Woodward Avenue. And he said, ‘What are you doing that for?’ I said, ‘It’s the Dream Cruise!’”

If Penske is the New York Yankees of motorsport, then the pace cars must be his championship spoils and the winning drivers his Lou Gehrigs, Joe DiMaggios and Derek Jeters. Dream Cruise is the clubhouse, and the highlight reel is loaded.

Welcome to the clubhouse.

1972, Hurst/Olds Cutlass. The start of something big.

The Hurst/Olds is unique among Indianapolis 500 pace cars. Hurst Performance developed it, not Oldsmobile, and its existence can be traced to 29 nonparticipant injuries at the Speedway a year prior.

In 1971, as the parade lap wound down, Indianapolis car dealer Eldon Palmer lost control of the Dodge Challenger pace car in the pit lane and smashed into a photographer’s stand. A handful of the injuries were serious. Those hurt in the car included longtime IMS owner Tony Hulman, astronaut John Glenn and ABC sportscaster Chris Schenkel, who suffered a broken shoulder and was unable to perform his television duties.

By 1972, fear of further bad publicity left the usual cast of pace-car suppliers hiding in the wings, so a performance parts builder stepped in. Oldsmobile supplied the Cameo White Cutlass Supremes, and Hurst did the rest. The Hurst/Olds is the only Indy pace car sponsored by a manufacturer other than an automaker and the first to include a supplier’s name. Exactly 629 ’72 Hurst/Olds were eventually sold to the public through a handful of dealers, with gold reflective stripes, the W-25 Ram Air hood, a 455-cubic-inch Rocket V8 (270 or 300 hp) and Turbo 400 automatic with console-mounted Hurst Dual-Gate shifter.

The Hurst/Olds is not one of the 10 worst pace cars ever. Nor was it the only notable bit of history at the 56th running of the Indianapolis 500. This was the first race to use the Electro-Pacer Light system of caution signals around the track and the first since the British invasion of the early 1960s with an All-American driver roster. On race morning, Hulman asked an actor best known for playing Gomer Pyle if he’d liked to sing “Back Home Again in Indiana” during prerace ceremonies. Jim Nabors accepted without rehearsing and would be the Speedway’s headliner for 42 years.

Most significantly, the 1972 Indy 500 ended with the first win for race driver-turned-team owner Roger Penske, in just his fourth try.

Penske’s Gary Bettenhausen dominated the first three-quarters of the race, leading 138 laps in his McLaren-Offenhauser. Ignition trouble parked him on lap 176. Running second or third much of the race, teammate Mark Donohue moved in front when Jerry Grant pitted on lap 188 and stayed there for the duration.

Bettenhausen’s hard luck aside, it’s appropriate Donohue collected Penske’s first Indy win. The 35-year-old driver/engineer known as Captain Nice had done more to establish Penske in the racing landscape than anyone but the team owner himself. Donohue would die from injuries suffered at the Austrian Grand Prix in August 1975. Team Penske’s racing complex in Mooresville, North Carolina, is still decorated with murals of Donohue in his race cars.

Penske was only starting. Engaged by automobiles since childhood in Cleveland, he drove his first race while in college at Lehigh. Sports Illustrated named him its Driver of the Year in 1961 based on his success racing sports cars. But by 1965, at 28, he was ready to retire as a driver to focus on building a team. In the half-century since, Penske’s teams have accumulated nearly 450 major race wins all the way up to Formula 1. He’s won 27 championships in Trans-Am, Can-Am, the USSRC, IMSA, NASCAR and IndyCar. He’s still winning at his favorite venue—the Indianapolis Motor Speedway—after Jim Nabors retired.

And that’s all been for grins. By 1972 Penske had set himself up in Detroit to build his expanding network of car dealerships. In 2015, after his 16th Indy win, the closely held Penske Corp. generates $23 billion in revenue from 3,300 locations worldwide, through one of the world’s largest dealership groups and interests in truck leasing, logistics, transportation component manufacturing, event promotion and internet publishing. Forbes estimates Penske’s personal wealth in excess of $1 billion.

“I think racing has been the common thread through our company,” Penske says. “Think about leading the Indianapolis 500 for a couple of hours at a time and think about what that does to your brand on a national basis. You couldn’t afford to buy that kind of TV time. The racing talks about execution, reliability. Certainly teamwork is key, and that’s what we try to promote through our company. We have (about) 50,000 employees today, but we run it as a small company. The guy driving the truck or jacking the car—his job is just as important (as mine), and he has to do it.”

1981, Buick Regal V6. The value of persistence.

The pace car started as a standard Regal coupe with the T-top option. The rear section of the roof was removed by the American Sunroof Co. and replaced by a half soft top, with an 8-inch-wide roll hoop where the B-pillars had been. This was before the turbocharged Grand Nationals and GNX, and the Regal’s standard 125-hp V6 required serious massaging to deliver the power needed for pace-car duty. Its basic shape was aero effective, nonetheless: Darrell Waltrip drove a Regal to two-straight Winston Cup championships for Junior Johnson in 1981-82. The 150 pace-car replicas the Speedway used in May were sold to the public without the ASC modifications or engine upgrades.

If the Regal pace car leaned toward the mundane, the 65th running proved one of the most controversial ever. Bobby Unser had already won an Indy 500 in each of the two previous decades, and he won another in his third season at Penske.

Unser started on the pole in a PC-7 Cosworth, but Gordon Johncock led 56 laps in the second half of the race before his engine began losing compression. Unser reassumed the lead on lap 182, with Mario Andretti hard after him. Andretti’s late fight for second with Vern Schuppan worked to Unser’s advantage and Unser was 10 car lengths ahead at the finish (a hair, in those days). Unser drank the milk for the third time, and Andretti was cheered for his charge from 32nd on the grid to second place.

Yet later that evening as ABC was airing its tape-delayed race broadcast, Speedway officials decided that Unser had passed cars illegally while leaving the pits under a yellow flag. He was assessed a one-lap penalty, and when official results were posted the next morning, Andretti was declared the winner. Penske appealed the results immediately after his initial protest was denied. The political winds seemed to blow in Andretti’s favor --perhaps because of his historic hard luck at Indy, or his charge from the last row at the start. The appeals hearing began nearly three weeks after race.

The United States Auto Club conducted the hearing like a court trial. Contemporary accounts say witnesses were asked dozens of questions that seemed to have no bearing on the issues at hand. The hearing was adjourned after the first day for another six weeks and once again after that. On Oct. 9, 1981, four months, two weeks after the race was run, the appeals panel announced its decision.

It voted 2-1 to restore Unser as the race winner.

Thirty-five years later, the logic behind the decision seems to be thus: Unser had, in fact, violated a vaguely defined “blend rule” in the regulations. Yet Andretti and other drivers seemed to have violated the same rule, and none (including Unser) was cited at the time. Two panel members concluded that, under the circumstances, Unser’s one-lap penalty was too stiff. He was fined $40,000 instead.

The drama might have contributed to Unser’s decision to retire after the ’81 season, but he’s sure about one thing: At age 81, he’s glad his third Indy win came driving for Penske.

“Roger and I had the same dedication to making sure that call was right,” he says. “We won the race, we were right in the rules and it finally came out that way. The only difference was that I wanted to file federal lawsuits, to find good, honest judges instead of that USAC kangaroo court. I think I was totally right in what I wanted and Roger talked me out of that one, ’cause Roger just cares about racing. He doesn’t want to sue people. He just wants to race.

“Here’s the last thing I’ll say about Roger Penske, and watch and see if I’m right. Everybody will have to admit at some point the he’s greatest, most successful team owner ever in the entire world. The guy can’t get enough of it.”

Unser’s willingness to litigate was apparent years later, after a life-threatening experience in the Colorado wilderness. In December 1996, he and friend Robert Gayton left Unser’s home in Chama, New Mexico, for a snowmobile trek. That afternoon, a wind-driven storm overtook them, eventually dumping 5 feet of snow. When the last of their two snowmobiles sputtered into immobility, they built a snow cave and ate snow to hydrate. After two nights they decided to walk in search of help. Some 15 miles later they stumbled upon a barn with a phone and a heater, and waited to be rescued.

Unser was later convicted of a federal misdemeanor for operating a snowmobile in protected wilderness, based on the location where his sled was recovered. He was fined $75, or $4,925 less than the maximum allowed. He appealed the decision all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court; it rejected his writ for a hearing in 1999.

In October 2010, 29 years to the month after he was affirmed the 65th Indy 500 winner, Unser testified before a congressional subcommittee on “over-criminalization” in federal statutes.

1987, Chrysler LeBaron. The value of quality.

This was not the five-door LeBaron GTS, a la Dodge Lancer Shelby. It was the new-generation, hidden-headlight J-car LeBaron convertible (and coupe), not yet offered with the upgrade V6. Within a couple model years, the demographics would demonstrate that the new LeBaron was still an old guy’s car.

That’s probably OK because the 71st Indianapolis 500 turned out to be an old guy’s race. At 47 years, 360 days, Al Unser Sr. was the oldest 500 winner ever.

If one can call a three-time Indy winner an underdog on Memorial Day, Unser Sr.—Bobby’s brother—was. After four seasons and two championships with Penske, Unser had retired from racing full time at the end of 1986. He went to the Speedway in May without a ride, largely to guide his 25-year-old son, Al Jr. Then Danny “the Flyin’ Hawaiian” Ongais crashed his Penske-entered PC-16-Chevy in practice, destroyed his car and suffered a concussion, benching him for the month. Penske offered the seat to Unser Sr.

First they needed a car, though. Penske found a year-old March chassis that had been on display in a hotel lobby a few weeks before and bolted in a dependable Cosworth DFV V8. Unser didn’t take his first practice laps until Wednesday after the first weekend of qualifying, but the next Saturday he got himself safely in the show. His 20th on the grid would be the deepest starting spot for any Penske Indy winner.

Mario Andretti had been fastest throughout the month and started from the pole. He led 170 of the first 177 laps before an electrical problem sent him to the pits. Unser Sr. took the lead with 18 to go, after Roberto Guerrero stalled during a stop. Those final 18 laps made Unser Sr. the all-time lap leader at the Speedway and only the second four-time winner in history.

It was another example of the Andretti Curse at Indy and another example of Unser Sr.’s uncanny ability to keep it running and off the wall, and to be there when it mattered most.

“When I was hanging around in ’87, I turned down probably six, seven teams because once you win that race, you basically know what it takes and you don’t want second-rate,” Unser says. “There are just so many things that can go wrong. If you can drive for a Roger Penske, your chances of winning grow rapidly.

“It might not be easy for fans to understand. Everybody always says, ‘We give 100 percent,’ but that 100 percent is divided, and parts are more important than others. Roger’s share of that 100 percent—he’s probably 75 percent capable of making sure the car can win. The other 25 percent just falls into place for the driver. Most teams might get you in the 30 percent bracket. Now the driver gets you somewhere past 50 percent, and what’s that do to your chances of winning? When your car owner puts up 75 percent, your 25 gets you a pretty good shot.”

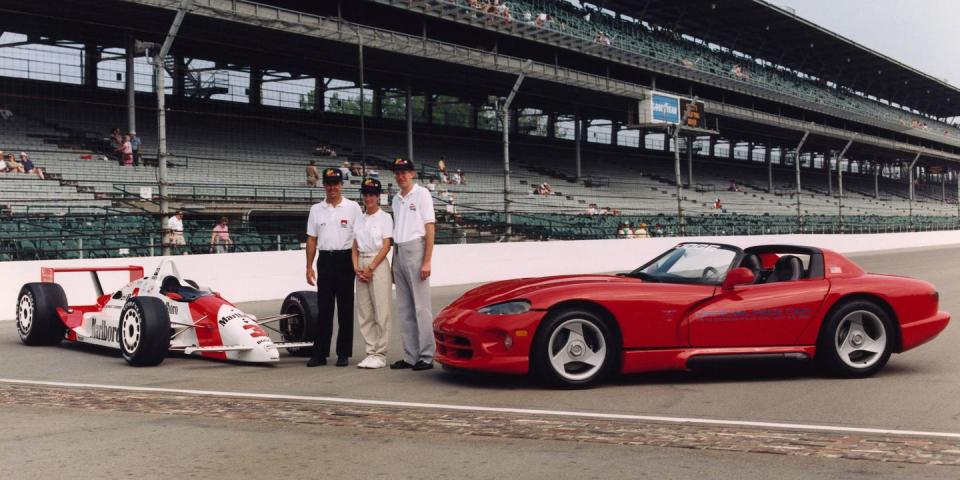

1991, Dodge Stealth and Viper RT/10. Consistency defined.

The Viper wasn’t part of the 75th Indianapolis 500 plan. Pace-car duty was originally reserved for the new Dodge Stealth—a fine car in its own right but also a re-badged Mitsubishi 3000GT engineered and manufactured in Japan. The United Auto Workers protested Dodge’s choice and fanned patriotic embers still glowing after the Persian Gulf War. Critics chastised Chrysler chairman Lee Iacocca—long known for various flag-waving sales pitches—for hypocrisy.

Dodge relented and replaced the Stealth last minute with the forthcoming Viper, built by the UAW in Detroit. Trouble was the Viper wouldn’t be launched until 1992, and the UAW was months from tightening its first Viper fastener. The 500 car was culled from the handful of existing development prototypes and the Speedway helped, bending its usual requirement for three legitimate pace cars. The roughly 160 Festival cars—driven by dignitaries at various functions in Indianapolis—remained Stealths.

It mattered only a bit to Rick Mears. He won his record-tying fourth 500 from his record-shattering sixth pole position and led the final 13 laps unchallenged, even through a restart with six to go. The worst of it was pain. Mears had his first Speedway wreck ever that May, aggravating a serious foot injury suffered years prior. Throughout the race, he frequently crossed his legs in the tub and worked the gas with his left foot to cope.

Born in Wichita, Kansas, in 1951, Mears was the first 500 winner born after World War II. With due respect to A.J. Foyt, he’s arguably the best Indy driver ever. His four wins came in substantially fewer tries than Foyt or Al Unser Sr. He finished in the top five nine times in 15 starts. In 2015, his 11 front-row qualifying runs look as unassailable as DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak.

Throw in three IndyCar season championships and an offer to drive for the Brabham Formula One team in 1980—Mears respectfully declined—and we’re left with a remarkable racing career. All with Team Penske.

“That stat (about Indy qualifying) is the one I like most,” says Mears. “What I like is that it shows the consistency, which is what I always tried to find—to be in there every time knocking on the door. It also shows the depth of the team supplying the equipment needed to get the job done race in, race out, year in, year out. It encompasses the quality of the operation.

“The only downside running for Roger was, when I first signed up—like, ‘Uh-oh, no more excuses. Got to put numbers on the board.’ But that’s way better than the pressure of trying to do more with less. Roger was a driver, and his approach was ‘whatever we gotta do to fix this thing and get it competitive, that’s what we want to do.’ Then his attention to detail—and just his desire to race and win races—separate him. You never had to fight for the tools needed to get the job done.”

In the early 1990s, Mears was expected to become the first five-time Indianapolis 500 winner. Then the year after his final victory, he qualified ninth and broke a wrist in the only crash he’d experience during the course of an Indy 500. He announced his retirement at season’s end.

Racers everywhere were stunned. In 1984, Mears had suffered a horrific crash at Sanair Super Speedway in Quebec; his shattered feet had to be surgically reconstructed. He spent three months in a hospital and 10 out of a race car. Thirty years hence, pain is a fact of life. “Just reminds me I’m still here,” Mears quips in his Reagan-esque fashion.

Yet two of his Indy wins came after the Sanair crash, and Mears was still near the top of his game. Speedway probabilities suggest, with a team like Penske at a place where experience matters as much as anything, he had five—maybe 10—competitive shots at a fifth win.

“The hardest part of deciding to retire was knowing how much that fifth win would mean to Roger and to the team,” he says. “I could take it or leave it at that point. Finally, I woke one morning thinking, ‘You know, if the desire is not there you’re not going to do the job necessary, and you’re not getting the fifth anyway.’ It was time to go, and I don’t regret the decision at all.”

Penske was nothing but understanding, according to Mears, but the owner knows a good thing when he sees it. He hired Mears as a consultant, and Mears has been imparting his wisdom to every Penske driver since.

1994, Ford Mustang Cobra. Risk, reward and seeds of trouble.

For the 78th running, the Penskes at Indianapolis were to other entrants as the Mustang Cobra pace car was to a standard Mustang GT.

The ’94 Cobra was Indy’s third Mustang pace car and the most recent Ford to date. It coincided with launch of codename SN-95—the first major Mustang overhaul in 15 years, based on an updated Fox platform. The SVT Cobra made 240 hp, or 25 more than the GT from the same 5.0-liter pushrod V8. Exactly 1,000 replicas of the ruby-and-tan convertible were built for public sale. Clean, relatively low-mileage examples can be located today for as little as $15,000.

This was the last year for Mario Andretti in an Indy car and a golden one for Team Penske—even if no one outside of Penske expected it. The previous winter, RP had taken advantage of his ownership stake in Ilmor Engineering and his role as a volume purveyor of Mercedes-Benz automobiles to secretly develop an engine that exploited a unique Speedway rule allowing cam-in-block engines an extra 0.9 liter of displacement and 10 psi more turbo boost.

Unveiled that May, the 209-cubic-inch Ilmor-Mercedes 500L—known widely as the pushrod engine—made something like 1,000 hp. The lingering question was whether it could last 500 miles.

It lasted. Penske cars led all but seven of the 200 laps, and it was settled when Emerson Fittipaldi spun himself out trying to get around Al Unser Jr. on lap 185 (cosmic retribution, perhaps, for an incident between the two in the 1989 500). Unser Jr. cruised through the final 15 laps and collected his second Indy 500 victory in his first season driving for Penske.

“No, no, no—no one but Roger could pull something like (the pushrod engine) off,” says Unser. “His connections. Resources. The development speed. It had a lot of power when we first started testing it, but it didn’t live. So we started detuning it—a little bit less power, every time we tested, a little more life. I told Roger: ‘If we can make it live 500 miles at Michigan (Speedway), then it’ll live at Indy.’”

The pushrod engine lived 500 miles at Michigan for the first time on May 7—the opening day of practice at Indy. While Unser was testing, Fittipaldi and teammate Paul Tracy were at the Speedway unveiling the car.

“I had a good feeling when I woke up race-day morning,” Unser says. “It was the only time I qualified on the front row (at Indy). I thought my teammates could be my only competitors. Matter of fact, Emerson was my only competitor. Tracy was starting in the back, and he’s Tracy. Emerson is a very smart race-car driver.”

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos