I Went to Monster Jam University to Learn How to Get Big Air in 1500-HP Trucks

The first thing you do after you start a monster truck is turn it off. Actually, you don't turn it off. One of the four guys watching you kills the ignition via a radio. You know how the Kool-Aid man used to crash through walls? They don't want that happening at your local arena should you go unconscious with the throttle wide open. Safety first.

"And what comes second?" I ask Tom Meents, the longtime driver of Maximum Destruction and the professor here at Monster Jam University in Paxton, Illinois. "Safety," he says. You can take a guess at the third most important thing. (Hint: It's safety.) “When do we get to the part about doing awesome stuff that looks supercool?" I ask. "That's fourth," he replies. I suppose that when a bunch of 'roided-out trucks with 66-inch tires and alky big-blocks start popping wheelies on a dirt track the size of a hockey rink, you've got to have some ground rules. It's like staging a dogfight between Black Hawk helicopters in the patio-and-garden section of your local Walmart. Don't knock over the petunias.

Meents is known for going big, making freestyle runs that look quasi out of control and attempting ludicrous stunts like the double backflip. The reality is that he's in perfect control (mostly) and the stunts were honed here, where two replica arena tracks are set among the soybean fields. It takes a lot of skill and composure to look demented and unhinged.

In contrast to his bombastic alter ego, Meents is laconic and deadpan. He suggests I should wear one of the school's three-layer fire-resistant driving suits rather than the vintage NASCAR one I brought with me, because "it would be a shame to have to graft part of your butt onto your face." In a Monster Jam movie, he'd be played by Woody Harrelson. He's been competing in Monster Jam for 25 years, and his 22-year-old son, Colton Eichelberger, is a driver now, too.

Could I be a driver? Many prospective drivers earn invitations to Monster Jam University by showing talent in related motorsports-say, off-road racing. But anybody can send in an application. Seriously. Superfans who petition for a tryout sometimes get a shot, in stark contrast to certain pro jai-alai leagues that constantly ignore my correspondence even though I know they signed for the Edible Arrangements. My chief qualification here is that one of my elementary schoolmates, Greg Winchenbach, drives Crushstation, the truck that looks like a lobster. So clearly, Jefferson, Maine, is a hotbed of monster-truck talent. Plus, I've got plenty of misplaced confidence, and I don't have a great grasp of consequences. You can't teach that, but I will have to learn the driving part.

For that, there are trainer trucks. These are not dumbed down or detuned; like the marquee Monster Jam trucks, they're running 1500 horsepower through a two-speed Powerglide transmission. The difference is the body. Since you'll just smash it up, and bodies are expensive-Max D's elaborate shells cost $16,000 a pop-the trainer trucks lack them. Standard procedure is to affix a sign bearing each driver's name to the side of the truck. This makes it look like my truck is named Ezra, which is a pretty weak name for a monster truck and would probably result in mine getting swirlies from BroDozer and Raminator.

Inside the garage, I climb up the frame and into the driver's seat. Chuck Werner, who drives El Toro Loco, tutors me on the controls while two mechanics adjust them. The lap belts are tightened with ratchet wrenches. It's important that everything feel right, because once you're strapped into the harness and head restraint, you can't see anything below your chin. In fact, your range of eye movement is really the only means of looking anywhere but dead ahead. If they could, they'd probably strap your eyeballs in place, too.

Once I'm bolted in, I get a thumbs up and fire the ignition. "Oftentimes, the best way to learn is from your failures," says Meents over the radio. "So let's get out there and start failing." We begin with a simple exercise: running ovals around a couple of tires to get accustomed to the rear steering, which is controlled by a toggle switch to the right of the steering wheel. Within a few laps, I feel I'm starting to figure it out. Meents lets me know that my badassitude is entirely in my head. "You look good," he says. "Slow, but good. You need to hit the rear steer early, let go of it early, and power out of the turn." I never quite nail the timing on that. It's a tough concept: Most of the steering comes from the back of the vehicle, via an on/off switch with a little bit of latency. I'm steering way too much with the wheel. Locking diffs and 66-inch tires don't want to turn.

It occurs to me that if this thing had a couple of electronically controlled diffs, it would have crazy turn-in plus the straight-line hookup. But monster trucks haven't followed the trajectory of every other form of motorsports, where competitors spend huge money for small advantages. Durability dictates design, and these trucks have evolved to survive abuse. They could always be quicker or more agile, but what good is that if you tear off your rear suspension every time you go big? "When the trucks were built for racing, they were around 9000 pounds," Meents says. "But for what we're doing now, they need to be built to take more abuse, so they're more like 12,000 pounds."

While nobody is running carbon-fiber rims or hybrid boost systems, the trucks aren't cheap. The number $250,000 is bandied about quite a bit. It's a number that's in my head-along with the hyperbolic weight and horsepower figures-as I pull to the green light that heads an impossibly short drag strip. It's maybe 70 feet long. Because, remember, you're essentially in a hockey rink. Meents kills the engine to coach me over the radio.

"Okay," he says. "You're gonna pull up to the line. Watch that light. Brake-torque it in first, bring the revs up. When you see green, pop your foot off the brake and go wide-open throttle through first, then bang second, and immediately get your hand up to the steering toggle. We're gonna do that three times. And then we're gonna do it with the engine on." He's not joking, and of course I mess up the sequence the first two tries. The radio crackles. "I think I know the problem," Meents says. "You've been in a million vehicles, but you've never learned to drive any of them!"

But somehow it's easier when the engine's running. The light goes green and I hammer down, all four Camry-sized contact patches digging for traction as a bushel of M-80s goes off behind my head and this second-floor studio apartment launches itself in the general direction of Iowa. It's probably something like the sensation a mountain goat feels the moment a golden eagle plucks it off a cliff. But I nail the run. I think. It turns out Meents agrees. "Let's see if you're lucky or good," he says. "Do it again." I repeat the process to his satisfaction and then take a break.

As I chug water, we sit at a picnic table under a shade tree and contemplate Maximum Destruction, parked in the center of the track atop the highest dirt pile. "Maybe you should drive that one," Meents says. "You can't break it. But it can break you. Physically and emotionally." Joke's on you, I say. I'm already physically and emotionally broken.

"How fast are these trucks, like, zero to 60?" I ask. "We've never measured that," Meents says, "but I know we can hit 80 mph in 500 feet for a jump. And on asphalt, it'll light up all four tires for a while off the line."

With the engine cooled down to 140 degrees, it's back in the truck for the next item on the curriculum: a jump. "This jump feels like you're 100 feet in the air," Meents says. "But it's probably only nine or 10 feet." Only? Later on, I will look at the heart-rate monitor on my watch and see that my heart rate doubled from 58 beats per minute to 116 during this feat, even though I was physically immobile. Translation: I was crapping myself.

The light goes green, and I willfully short-circuit any part of my nervous system that's not onboard with holding my right foot down. Revs up, pop the brake, the nose of the truck climbs skyward for the quick rip through first gear. Slam second, keep it straight, watch the ramp rush toward the front tires before falling away as the truck goes weightless for what must be the longest second of my life. Limit straps keep the axles from ripping the dampers apart at full droop. The landing is flat, pretty much, and amazingly smooth. "Good, good!" Meents yells over the radio. He's kind of laughing as he says it. I think he's pleasantly surprised that I actually listened to his advice and kept the throttle down. He sends me back around for another run. This time, I'm excited rather than terrified, because jumping a monster truck is exactly as much fun as you'd hope it would be. I do it again, this time staying on the gas just a little bit longer and sticking the landing that much cleaner. "Perfect!" Meents yells. "Good job, good air, truck was nice and level. Maybe you could've backed off sooner, but don't overthink it." He decides to promote me to Monster Jam 102: Stoppies.

This is a relatively new trick, in which the driver kicks the rear tires off a steep lip, then jams the brakes to send the truck up onto its front tires. The experts can balance the truck on the front tires, rears skyward, seemingly forever, even shifting into reverse and driving backward (a.k.a. moonwalking). But it's not easy. Earlier this morning, we watched Eichelberger give a demo, and even he rolled it a couple times. "There are two kinds of drivers," Meents says. "Those who have flipped and those who haven't." He leaves out the "yet." It's assumed.

Would you believe that I nail the stoppie on the first try? Well then you are gullible. But almost. I goose the throttle, the back end does a mule kick, and I stand on the brakes. The view ahead rotates from blue sky and green fields to the dirt immediately in front of the truck. The truck teeters for a moment before toppling over like a giant robot dog looking for a belly rub. There's a term for this: I turtled it.

"You had it!" Meents says. "Good throttle, good timing, you just needed to let off the brake and maybe give it a little bit of gas. But you had it." Here I am hanging upside down like an idiot, and Meents sounds almost happy about it. Maybe even a little proud. There are two kinds of drivers, and now I'm the right kind.

Monster Mash

These trucks are built for durability beyond all else. Here's what goes into their 12,000-pound curb weights.

Engine: A 540-cubic-inch, 1500-hp alcohol-burning big-block. Like the suspension, there are limit straps here, too-on the supercharger, in case it blows up. Most trucks are mid-engined.

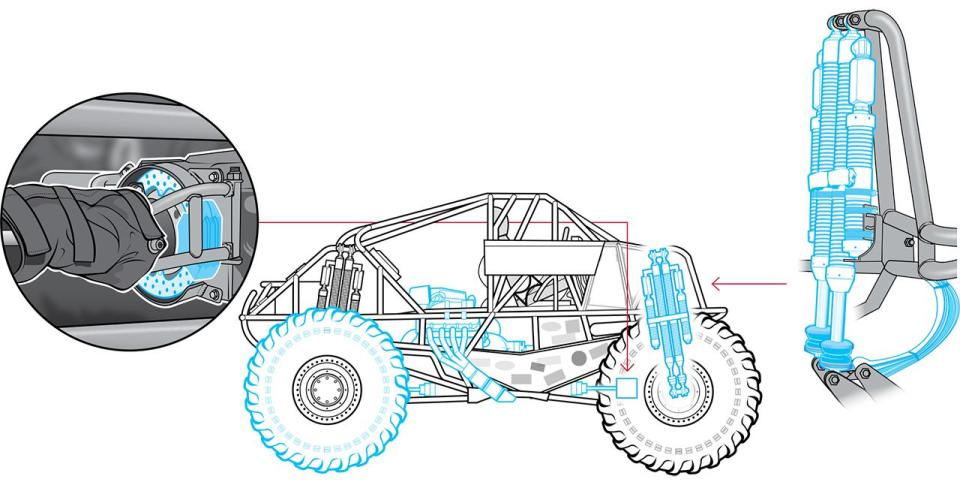

Suspension: Thirty inches of travel, with a four-link rear end that can withstand vertical drops from crowd-pleasing flying wheelies. Limit straps prevent the ZF axle assemblies from tearing apart the dampers at full droop.

Brakes: A single 12-inch rotor for each axle. These pinion brakes are mounted between the drive-shafts and the axles, multiplying the braking force by the 22:1 gear reduction.

Tires: Sixty-six-inch-tall BKTs designed for Monster Jam trucks. They're lighter than agricultural tires. Beadlock wheels are a necessity.

Mufflers: Stubby MagnaFlows welded in just aft of the headers. Don't worry, it's still loud.

The Physics of a Stoppie

Get it right and you're a gravity-defying hero. Screw it up and you're upside down.

One of the reasons Tom Meents likes the engine mounted in front in his truck: When he's doing a stoppie, a.k.a. putting the thing on its nose, the truck's center of gravity is that much lower. This is how it's done:

1. With the front tires at the top of a short, steep ramp, brake-torque the truck.

2. As you release the brake, floor the throttle. When the rear tires hit the ramp, the truck will mule-kick skyward.

3. The moment you feel the rears kick up, slam the brakes. With the front tires on the ground, this will cause the rear end to continue rotating up.

4. When the rear end is straight up or close to it, release the brakes to let the front tires start walking forward. Once you find the balance point, drive around like this all day.

5. Or hold the brakes too long and the momentum of the rear carries past the balance point . . .

6. . . . and you turtle.

('You Might Also Like',)

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos