Why my lawnmower is electric but my car isn’t

Rick Newman is a senior columnist for Yahoo Finance.

I bought my first battery-powered lawnmower nearly 10 years ago as an experiment. It was a success, and most of the other machines in my garage — trimmer, weed whacker, chain saw, rototiller, leaf blower, snow thrower — are now powered by batteries I recharge from an electrical outlet.

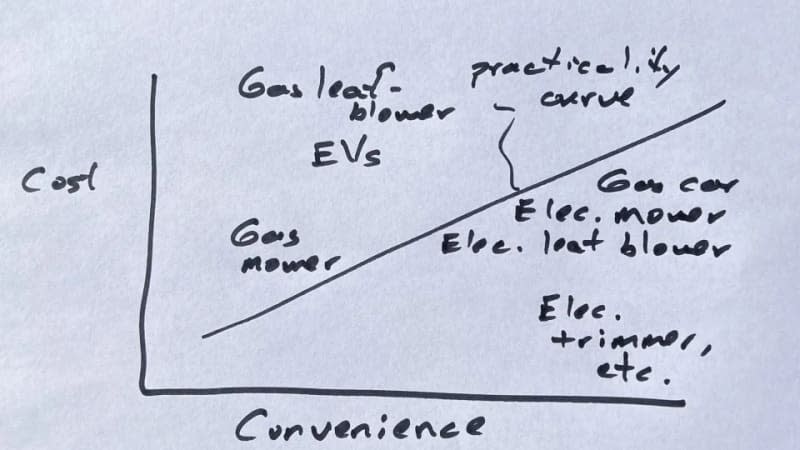

My car, however, is not electric, and I still don’t foresee a day when I’ll choose an electric vehicle over a gasoline-powered one. I love EV technology, and I’m glad most automakers are rolling out electrics. But EVs are too far above the practicality curve for me, and it’s not clear if or when they’ll fall inside it.

The choices on display in my garage are now playing out in the broader market for EVs, where automakers are beginning to pause aggressive efforts to transition rapidly from gas-powered cars to electrics. EV sales are still growing. They’ve jumped from barely nothing a few years ago to 8% of all new car sales. But demand seems to be flagging, forcing automakers to cut prices for EVs, which are not profitable yet for most companies that make them.

Ford, General Motors, Honda, and Volkswagen have scaled back EV plans recently or warned about disappointing sales. Even high-flying Tesla, which only makes electrics and lost money for 14 years before turning its first profit in 2020, is slashing prices and delaying the opening of a new factory in Mexico.

None of this means EVs are a failure. The difficulty most automakers face is predicting adoption rates for the new technology and adjusting their production plans to match what is basically a moving target. Retooling assembly lines to switch from gas-powered cars to electrics is cumbersome and expensive. So is opening new factories to build EVs or components such as the big battery packs they require.

Rising interest rates, meanwhile, are forcing buyers to change their plans. And now, the type of fuel that powers your car has become a political issue. Former President Donald Trump has decided EVs = bad, calling them the “ridiculous all-electric car hoax.” He’s wrong. EVs are here to stay. But they’re not for everybody, and in addition to all the other considerations involving a car, potential buyers now have to ask whether an EV fits their political brand.

The biggest unknown about EVs is how much of the market they’ll constitute at any given point in time, and how to get the supply-demand balance right. President Biden, who promised to “end fossil fuel” as a presidential candidate in 2019, wants half of all new cars to be zero-emission vehicles by 2030. For the most part, that means electrics. But Biden can’t force people to buy EVs. He can only set regulations and sign legislation giving them reason to do so, such as the EV tax credits that were in last year’s Inflation Reduction Act.

Evaluating the pros and cons of electrification as you move up the appliance chain from power tools to automobiles helps explain why there may be a demand ceiling for current EV technology. My battery-powered lawnmower is a hit because the technology forces no tradeoffs on me. It cost a little bit more than a gas-powered model, but there’s no gasoline, oil, or other messy fluids, and I charge it at home. There’s basically no maintenance, either. You just pop in a fresh battery and start it up like you would a vacuum cleaner. It’s quieter than gas mowers, and I don’t pollute the air or breathe in carcinogens while mowing.

As I was writing this story, I decided to scribble some ways of measuring the usefulness of various gizmos, and ended up drawing my personal practicality curve, as you can see below. There are no numerical values associated with the various products I’ve plotted on this chart. All I want to convey is the relative appeal of different types of products, based on what I value as a consumer.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos