Who Wins in the Autonomous-Car Economy?

Long before mobility became an auto-industry buzzword, before partyers could summon a ride via an app on something called an iPhone, and before Silicon Valley and Detroit became alleged rivals, William Clay Ford Jr. could foresee the tectonic forces pushing to upend traditional transportation.

As early as the turn of this century, he prodded Ford Motor Company to reckon with a future that would demand more energy efficiency and pollution reduction from its vehicles while also understanding that future populations would be more concentrated in megacities that couldn’t absorb additional traffic. In 2007, with a mind toward creating business models that matched such a future, he proposed that the company explore alternate modes of transit. “I’m not sure the term ‘mobility’ existed, but I wanted to invest in transportation solutions that were different,” Ford says.

A few years before that, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency lured a band of engineering geeks to the Mojave Desert for a competition, offering a seven-figure prize to the team that ran a driverless vehicle through its grueling off-road course the fastest. No car made it farther than 7.4 miles into the 142-mile course of the first DARPA Grand Challenge. Five robocars completed the race the following year, and in the rapid progress of subsequent Challenges, Google saw enough promise in the technology to launch its own automated-car project in 2009.

Those decisions have proved prescient. Venture capitalists poured more than $1 billion into automotive-related tech companies in 2016, and they’ve already surpassed $2.6 billion in such investments throughout the first eight months of this year, according to CB Insights, a market analytics firm. Silicon Valley tech giants, startups, and traditional automakers alike are rushing to address potential new markets as a result.

It’s easy to see why. The worldwide auto industry took in $2.3 trillion in revenue in 2016, but revenues associated with mobility services—a term the covers everything from Uber to traditional taxis and buses—totaled $5.4 trillion.

Automated-vehicle technology is already reaching the market in the form of slow-moving shuttle buses and advanced driver-assist features. But as we’ve seen in this package, fully automated cars, the kind that can take riders anywhere they want to go under any condition, are still at least a decade away from widespread deployment. While no one can say for sure how they’ll get to market or what their ultimate use cases will be, it’s easy to imagine a world in which robocars will enable passengers to turn their attention toward work or entertainment and let manufacturers unleash new mobility services.

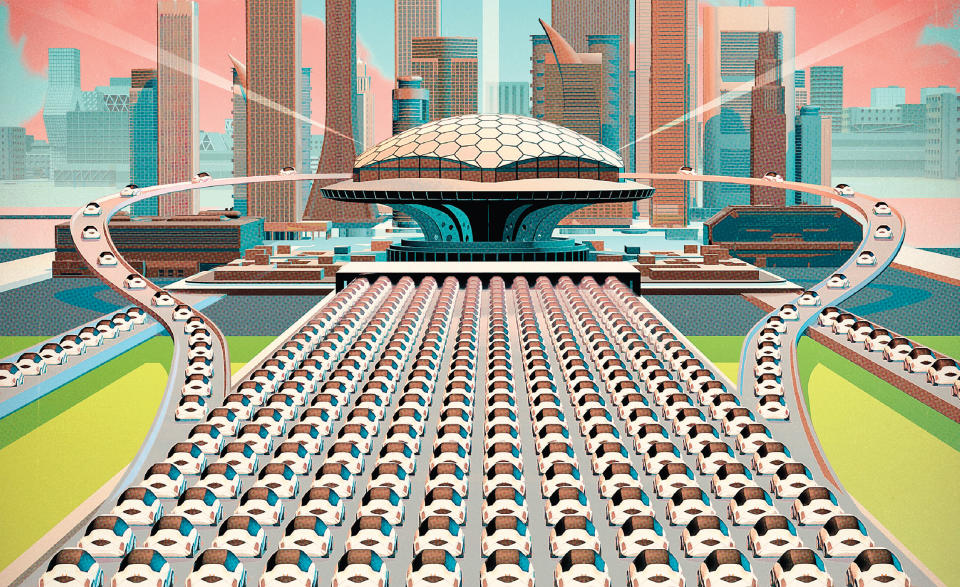

A 2017 report from global consulting firm Strategy Analytics predicts that, once they mature and achieve widespread use in 2035, Level 5 vehicles will be an economic powerhouse that will ripple through both the business and consumer sectors and should generate as much as $7 trillion in revenue by 2050. The scope of these changes, wrought by what the report’s author calls “the Passenger Economy,” cannot be overstated.

In 1950, approximately 30 percent of the world’s population lived in urban areas. Fast-forward a century, and two-thirds of the world’s population is expected to reside in urban areas. This boom will outstrip the capacity of public transportation options and tax existing road and parking infrastructure, leading more people to use mobility-as-a-service options, which will account for $3.7 trillion of those revenues, according to the report.

Businesses will use these services to reshape their fundamental operations, which will account for $3 trillion in revenue. “We’re going to be moving packages autonomously before we’re moving people autonomously,” says Kevin Vasconi, executive vice president and chief information officer at Domino’s Pizza.

“On the extreme end, we could see the evolution of RVs into autonomous houses that trundle along and nomadic communities that follow work patterns. These are twinkles in people’s eyes, and it’s hard to take full account of that in 2017.” _ Doug Davis, senior VP of Intel’s Automated Driving Group

More employees will work in their cars as driverless mobility frees up more than 250 million collective hours spent in vehicles each year, according to Strategy Analytics. An entire new economy will rise around the 5G-connected services that will drive this mobile workplace. A recent Qualcomm study estimates 5G could spur as much as $12.3 trillion in revenue for the automotive sector in 2035.

Full automation is predicted to lead to safety benefits that provide economic and societal benefits. In 2010, NHTSA estimated that car crashes cost the United States $871 billion in losses, equal to roughly 5 percent of the country’s gross domestic product at that time. Meanwhile, as many as 30 million Americans who previously couldn’t drive due to age or disability will exert newfound independence and influence on the economy.

For all the hyped changes, though, some things may remain remarkably consistent. As much as they’ll continue to morph into service providers, automakers are likely to sell more vehicles, not fewer. Silicon Valley companies such as Waymo, the commercial-minded descendant of Google’s automated-vehicle project, have eschewed development of their own computer-controlled vehicles in favor of partnerships with established manufacturers.

Existing ride-hailing services such as Uber might be a big boon for traditional automakers, too. Cars used in such services will reach the end of their life cycles faster than personal vehicles, presenting more frequent sales opportunities for OEMs.

It’s worth remembering that, although you wouldn’t know it from many of their stock prices, traditional automakers remain in strong positions with an entrenched business model that shows little sign of a mobility revolution afoot. Three-quarters of Americans drive alone to work, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, and the rate of carpooling has declined during each decade since 1980. The number of new-vehicle sales in the States reached an all-time high in 2016 with 17.6 million units, per Autodata. And the number of vehicle miles Americans travel annually has increased for five consecutive years; 2016’s 3.2-trillion-mile estimate marked a new record, according to the Federal Highway Administration.

“People are going to tenaciously cling to their ability to own and drive their own cars, and I think that won’t go away for a very long time,” says Roger Lanctot, author of the Strategy Analytics report.

What may change as automation evolves over the next couple of decades are the types of vehicles and interior environments that automakers will offer. “We’ll see a whole new rash of vehicle types adapted to local circumstances,” says Doug Davis, senior vice president of Intel’s Automated Driving Group. “On the extreme end, we could see the evolution of RVs into autonomous houses that trundle along and nomadic communities that follow work patterns. These are twinkles in people’s eyes, and it’s hard to take full account of that in 2017.”

For all the predictions, though, there is one underlying fragility. As noted elsewhere in this package, automated vehicles still face a myriad of liability hurdles, regulatory obstacles, to-be-determined safety benchmarks, and other complications presented by the technology itself. Any delay in their rollout could have dire ramifications for ride-hailing companies such as Lyft and Uber, whose business models are dependent on their arrival.

Human drivers account for 45 percent of ride-hailing services’ operating costs, according to management consulting firm McKinsey & Company. As these companies burn through money—Uber lost $2.8 billion in 2016, according to Bloomberg—driverless technology represents a path toward financial solvency. Yet Uber’s driverless program has floundered amid a lawsuit with Waymo over alleged stolen trade secrets. And Lyft’s cofounder and president John Zimmer acknowledged in July that human drivers “will always” play some role in the company’s operations.

“If Lyft is depending on driverless taxis in the near term to sustain profitability, I’d be worried if I were them,” says Eric Paul Dennis, a transportation systems analyst at the Center for Automotive Research.

For a ride-hailing company such as Uber, any slowdown in the march toward automation may represent an existential threat. For traditional automakers, on the other hand, automation represents an evolving pivot, and they’re well positioned to wait for their bets to mature while enjoying a healthy status quo.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos