The woodgrained Nash Rambler Cross Country wagon is an unintentional postmodern masterpiece

Consider the depot hack, progenitor of the station wagon as we know it. An exposed wood body on a rugged chassis—a Ford Model T, let’s say. Humble. Hardworking. Charming to modern eyes, depot hacks were a product of necessity, that being the need to move people and goods cost-effectively; their execution presents an interesting blend of mass-produced machinery and hand-hewn wood.

There’s a vague Arts and Crafts sensibility to the effort. Whatever William Morris would have thought of the methods of mass production, he surely would have had some appreciation for the depot hack’s fundamental honesty—the way it showcases natural materials and the craftsman's skill in shaping them.

Once manufacturers figured out how to make large, enclosed steel auto bodies and the amount of wood used in vehicles shrank, the depot hack's all-timber approach became an anachronism. But "woodies" carried on, at least for a few decades. In some cases, like the short-lived postwar Packard Station Sedans, a semi-wood construction offered automakers a somewhat cost-effective approach to building low-volume vehicles. By this point wood had evolved into a totem of suburban gentility, as exemplified by vehicles like Chrysler's Town and Country.

With the introduction of (relatively) durable, (relatively) realistic photo-reproduced plastic woodgrain, even this notion was driven into the ground; by the 1970s, woodgrain had become a shameless add-on, an attempt by automakers to dress up their humble designs or maybe charge a little bit more for a “luxurious” trim.

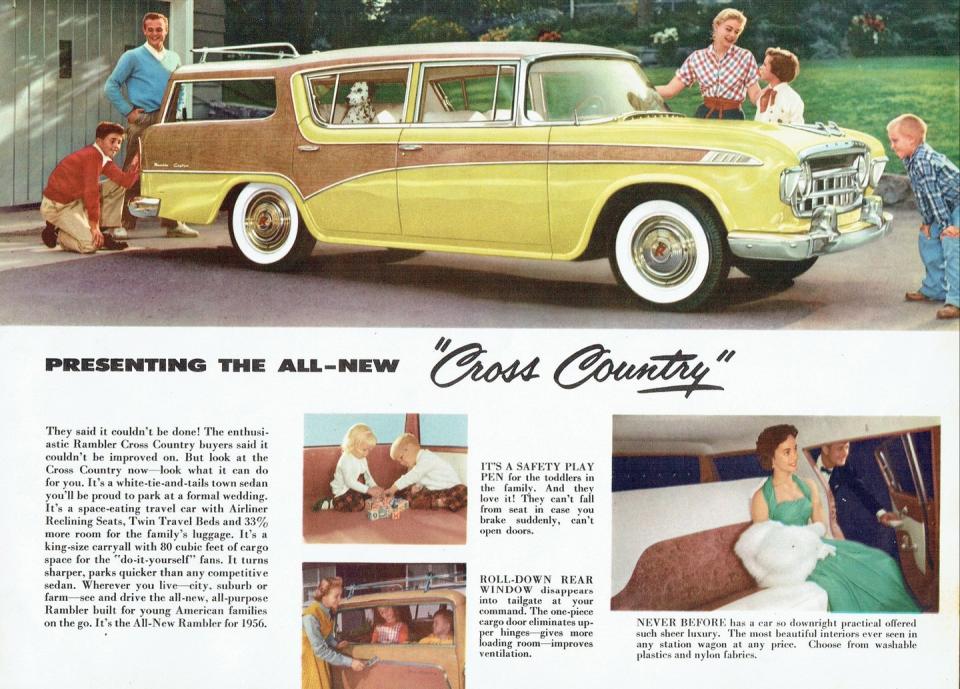

In the middle of all of this is the 1956 Nash Rambler Cross Country wagon, an automotive artifact so complex that we need to lean on the theories of postmodern architect Robert Venturi to decode it.

For some background, know that the Nash Rambler wagons were introduced in 1951 and by 1953 had received a swoopy redesign. Nashes were recognized as sensible, economical cars, and the wagon variants were even more sensible; they proved to be popular products for the independent automaker, helping it through some of its most challenging years. Importantly, upper trim level cars could be had with woodgrain accents.

American Motors, formed by combining Nash-Kelvinator and Hudson in mid-1954, was by 1956 ready to roll out a new line of Ramblers. Offered as either Nashes or Hudsons, these were a far cry from the tubby Ramblers of “Beep Beep” fame, but familiar old names—including Cross Country—made the jump to the flamboyant new designs. All of them, including the four-door wagons, were powered by an inline-six motor.

The Cross Country wagons are rare sights today, and when they do turn up they're usually wearing a flashy "tritone" paintjob. But, as with previous generations, they could also be had with woodgrain, and these are truly a sight to behold. There are countless board-feet of faux-wood here, but it's the way it's used that's groundbreaking: It runs across the sides of the wagons, obviously, but from there it wraps around the upper half of the drop-down tailgate with roll-down window (an industry first). Bizarrely, it also creeps up the C- and D-pillars, where it blends, unbroken, with the thin strip above the windows.

Compare this treatment with the Jeep Grand Wagoneer. Though the Jeep's woodgrain is all vinyl and plastic, you could replace it with pieces of veneer framed by genuine wood (a few owners have done this over the years, for whatever reasons), and it would have basically the same effect. The Rambler Cross Country, in contrast, uses stick-on woodgrain in a way that no one building a car with real, structural wood ever would—or, indeed, ever could. Imagine the sheet of veneer you'd need to accomplish it! Good luck getting it to stick to the complex shapes of the tailgate.

The Cross Country doesn't attempt to fool you into thinking its woodgrain is wood—or that it could ever be wood. It is woodgrain as woodgrain, totally honest in its artificiality. It is a postmodern masterpiece, albeit an almost certainly unintentional one. Morris would be baffled. Enraged, even! But I bet Venturi loved it.

Venturi, who died in 2018, designed a number of buildings that are widely considered to be Important, which is to say that they're not very attractive and are probably dreadful to live in, but which make a lot of very smart people rub their chins and tut-tut knowingly when they come up in conversation. No matter—his writings on architecture, done in collaboration with his wife Denise Scott Brown and others, are more relevant to our Rambler examination.

Discussing symbolism in architecture, Venturi famously contrasted the theoretical “duck”—a duck-shaped exercise in programmatic design based on a Long Island egg stand—with the “decorated shed,” a basic minimalist structure plastered with ornamentation. The appearance of the decorated shed is completely removed from its structure—removed, even, from what's going on inside. (You could take all the columns off of the outside of Caesars Palace, for example, and it wouldn't be any less a Las Vegas casino complex once you walked through the doors).

Most woodies, at least the ones in the pre-vinyl woodgrain days, are ducks. Their undeniable symbolic power comes from their form, which is dictated by the material from which they are built. The Rambler Cross Country is a decorated shed; there is no relationship between the woodgrain on its sides and the underlying structure of the vehicle—most of these wagons were built without woodgrain, after all. The same could be said of all of the woodgrained vehicles that followed it (which, owing to nostalgia, now have a symbolic power of their own). But the Rambler takes it a step further than most in both conception and execution, and that’s what elevates it to art.

By 1957, things had mellowed out at AMC; woodgrain was reduced to a spear running along the car’s beltline. A solitary dip ahead of the rear wheel well is the sole reminder of the previous model year’s exuberance. The prior represents a high water mark for woodgrain, a moment where a new material inspired by an ancient material was used in a manner almost totally divorced from context.

In the process, the stylists at AMC created in the 1956 Rambler—as with many works of genius, likely without realizing it—a postmodernist automotive masterpiece. Beep, beep!

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos