Yearslong war on Asian carp showing some progress, but end is uncertain

Wade White was bow fishing on the Cumberland River in a Jon boat below Barkley Dam in Western Kentucky one night about eight or 10 years ago when he was startled to see a sizable fish go airborne and land in his boat.

“I had no idea what it was,” White recalled. “I thought, how did this fish fly through the air like it did?”

“Everything was dark,” he said. “It scared us all to death. We didn’t know what had happened.”

That was the first, but certainly not the last time, that an invasive Asian carp, specifically a silver carp — spooked by the sound of a boat motor — had leapt out of the water and landed in a boat with him.

White is a lifelong fisherman who lives near and regularly fishes on Lake Barkley. He had been aware that Asian carp — one of several invasive species of fish in U.S. waters — had made their way into rivers and lakes stretching from Mississippi to Minnesota, including Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois.

It wasn’t long before videos, news stories and anecdotes emerged about Asian carp — carp flying in the air as boats approached, carp smashing into people’s heads, waters seemingly boiling with carp, carp possibly crowding out native species like bass that draw sport and professional fishermen.

White was also the county judge/executive of Lyon County, Kentucky, a community on the shores of Lake Barkley that, along with the adjoining Kentucky Lake, are the crown jewels of Western Kentucky tourism and sportfishing.

As such, White felt compelled to seek measures to protect the huge reservoirs from these invasive species for the sake of tourists — boaters, skiers, fishermen — and the untold numbers of folks who own lakeside homes for weekend relaxation or their retirement years.

But he could hardly have imagined how he would become engaged with what became known as the War on Carp in the years that followed.

And there was no certainty that, as the 2023 tourism season approaches, that there would be cause for cautious optimism.

The origin story

What Americans call Asian carp — species such as silver, bighead, grass and black carp — have long been coveted, even mythologized, in Asia as a food source; there is evidence of carp aquaculture (fish farms) in China dating back thousands of years.

It’s widely reported that Asian carp species were introduced to the United States during the 1970s and 1980s at private fish farms and wastewater treatment facilities to reduce algae growth and improve water quality in those ponds.

By the 1990s, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service says, they had begun escaping into the Mississippi River. Worse, they began successfully reproducing in U.S. waters.

Asian carp have been documented throughout the Mississippi River Basin and its tributaries, including the Ohio River, the Wabash and Green rivers and, in far-Western Kentucky, the lower Cumberland and Tennessee rivers.

For a time, White and others hoped that the unwanted guests wouldn’t make their way upstream from the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers into Lake Barkley and Kentucky Lake.

But get into the lakes they did, traveling alongside barges and other craft that navigated upstream from the rivers through the locks at Barkley Dam and Kentucky Dam into the two immense reservoirs.

“From 2013 to 2017, Barkley and Kentucky were really saturated with adult silver carp,” according to Joshua Tompkins, fisheries program coordinator for the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources’s critical species investigations.

Jumping Jehoshaphat

The growing numbers of silver and bighead carp in particular were worrying for multiple reasons.

First and most visible is that silver carp can come flying out of the water when spooked by the sound of or vibrations from an outboard motor or personal watercraft, particularly in shallower waters. And not just one or two carp, but sometimes dozens at a time.

Silver carp can grow to 20 pounds or larger and can leap several feet above the water line, which can make boating and skiing hazardous on some waters. (Bighead carp can grow to more than 100 pounds but are far less likely to leap from the water.)

As early as 2007, “Several boaters have suffered injuries from leaping silver carp, including broken jaws, noses, ribs, arms and legs after being hit by flying carp,” according to the National Wildlife Federation.

In 2015, a 19-year-old Illinois man was struck in the face by a leaping carp while he was being pulled on an inner tube by a boat driven by his father along the Mississippi River. The collision fractured his nose and broke bones above his eye brow; surgery to repair his face took 3½ hours, according to a news report.

“With a boat speed of over 20 mph and fish that can weigh over 20 pounds, this can be disastrous,” according to the U.S. Geological Survey, which is the scientific arm of the Department of the Interior. “Jumping fish have seriously injured many boaters and damaged boats. Water skiing on the Missouri River is now exceedingly dangerous because most of the fish jump behind the boat.”

One Henderson father said he stopped taking his family for weekend trips to the lakes after a spooked silvery carp landed in his daughter’s lap while she was inner-tubing.

“It got to the point it was driving tourists away (because of silver carp) leaping in air, landing in boats,” White said (though biologists say jumping carp are a much greater threat in shallower and narrower waterways such as the Illinois River than Barkley and Kentucky lakes, which are vastly wider and deeper).

Growing numbers

Second, Asian carp are prolific reproducers.

“Three species of carps (bighead, silver, and grass) are reproducing at alarming rates and threaten Kentucky’s aquatic ecology,” Kentucky Fish and Wildlife’s website declares. Females can produce over 1 million eggs a year, it said.

That’s true, but that would be for a “very large” female said Duane Chapman, a research fish biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey and one of the nation’s foremost authorities on Asian carp.

“We estimated that one very large bighead carp, over 100 pounds, had roughly 3.5 million eggs,” Chapman said in one of a series of email responses to a reporter’s questions. “A first spawn by a youngish female silver carp might have 60 (thousand) to 150K eggs.”

A pressing concern for Lake Barkley and Kentucky Lake was whether the carp could successfully reproduce in those reservoirs.

In 2015, a “really big” number of Asian carp eggs hatched in the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers just below Barkley Dam and Kentucky Dam, respectively, “just enormous numbers of juvenile invasive carp in the tailwaters below both dams,” probably totaling “millions and millions” of young fish, according to Adam Martin, the fisheries program coordinator for Kentucky Fish and Wildlife’s Western Fishery District.

Young carp were found that year in the lakes themselves. “That indicates it was possible they spawned in the lakes themselves,” Martin said, which was alarming. If Asian carp could successfully spawn in the lakes, they could take over those ecosystems.

“It was never confirmed by Kentucky or Tennessee wildlife agencies,” Tompkins said. “It’s likely there was some spawning, but it was never validated.”

But there is promising news. “Since then, there has been no sign of successful reproduction, even in the tailwaters,” Martin said.

“It’s difficult to say” why the carp don’t seem to be reproducing in the lakes, he said, “but the most logical theory” is that successful spawning requires turbulent water that keeps females’ eggs suspended long enough to come in contact with male sperm. “If there is slack water with no current, the eggs will sink to the bottom and die.”

Still, successful reproduction is documented in other U.S. waters, and adults have been able to migrate through the locks to the twin lakes.

Food fight

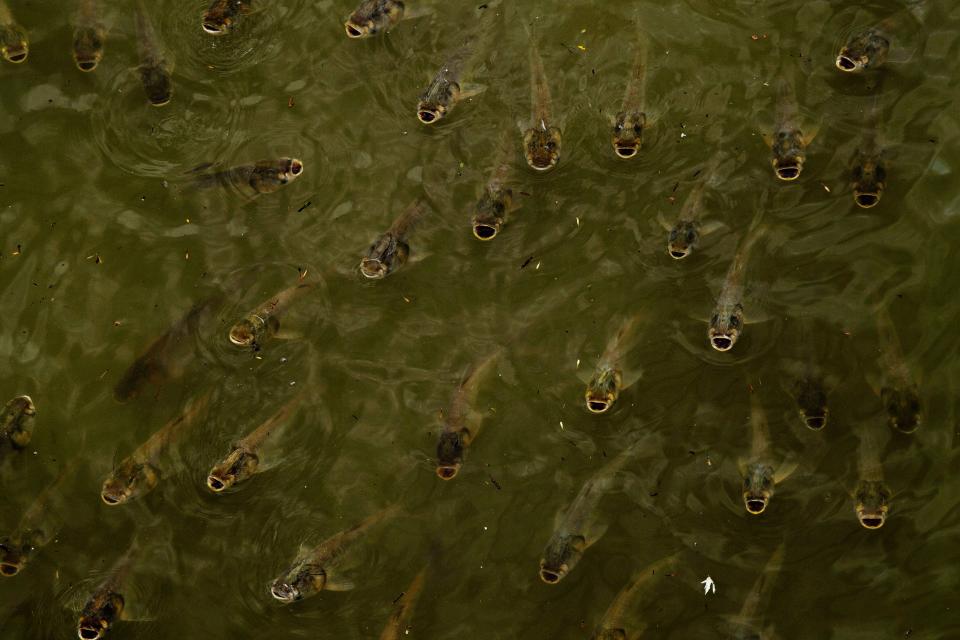

Third, silver and bighead carp feed on plankton, which is a crucial food source for young fish called fry as well as small bait (or forage) fish such as minnows that gamefish feed on. Fish biologists say the Asian carp feed almost continuously, their large, toothless mouths open, taking in plankton that they filter from the water.

“In Kentucky, invasive carp … are outcompeting native fishes for forage,” according to the Kentucky Fish and Wildlife website.

“Asian carp not only out-compete native sport fish like crappie and largemouth bass, but some species feed on the freshwater mussels that help keep our aquatic systems healthy by providing good fishing and good water quality for people, waterfowl and other wildlife species,” Allan Brown, assistant regional director for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, testified before a U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee in 2018.

“Fishermen stopped coming (to the lakes) because carp overwhelmed all other populations,” White said. “They’d go into a bay and filter out all the good stuff the little fry eat. There was hardly any live bait in the water.”

The idea that invasive carp could outcompete native species by consuming the plankton that fry and bait fish rely on to become the dominant species was alarming.

But biologist Martin has some doubts.

“There is very little chance of dietary overlap between adult silver carp and juvenile bass and crappie,” he said. “The adults are only feeding on offshore plankton” while young sportfish such as bass “are hiding out near shore.”

Further, Martin declared, “There are zero studies that evaluated dietary overlap between juvenile sportfish and juvenile silver carp.”

The issue “has been inadequately researched, in regard to young sportfish,” the USGS’ Chapman agreed. “It is a hard question to research effectively.”

But the fact that there are a lot of Asian carp in the region’s rivers and lake remains worrisome.

And they can grow quickly “if the resources (such as food) are there,” Chapman said.

What to do?

There has been plenty of handwringing, sure, but there have also been plenty of strategies to try to control Asian carp.

Since 2005, volunteers have gone out on Jon boats, pontoon boats and other craft with haul nets to snag flying silver carp out of the air during the annual Redneck Fishing Tournament on the Illinois River near little Bath, Illinois. Last year, the teams (some of whose members wore helmets to protect them from possible head strikes from a flying silver carp) removed 3,000 carp totaling some 20,000 pounds, according to one news report.

Plenty of people hunt and kill them with bow and arrows, often for sport but also for the satisfaction of relieving the U.S. of some of the invasive carp.

Asian carp bowfishing tournaments have even been organized. In August 2022, for example, Aquatic Protein LLC, which operates a fish-processing plant in Beardstown, Illinois, sponsored its third annual bowfishing tournament at Barkley Dam for harvesting Asian carp. The winning team brought in 1,934 pounds of fish and was awarded top prize of $3,000. Three other teams of brought in more than a half-ton of fish. Aquatic Protein, which produces fish oils, fertilizer and dog and cat food from the carp, paid 9 cents per pound for the fish brought to its receiving station at Eddyville.

“We have a pretty strong bowfishing community in Western Kentucky” that particularly target the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers, just below the dams, Tompkins said.

“In 2021, bowfishing harvested around 300,000 pounds” out of those waters, he said.

On the menu

Meanwhile, because Asian carp are, in fact, a tasty white fish, there have been multiple attempts to encourage Americans to eat them.

It hasn’t been simple. When most Americans think of “carp,” they think of the common carp that was imported from Europe in the 19th century and is regarded as the proverbial bottom-feeding scum sucker — a muddy-tasting trash fish.

Asian carp, however, aren’t bottom feeders; they are filter feeders who consume plankton and algae. The U.S. Geological Survey declares “Asian carp of all types have white, firm, mild flesh, which is excellent table fare.”

More than a decade ago, there were efforts to rebrand Asian carp as “white fin,” “Kentucky white fish” or “Kentucky tuna.”

French Chef Philippe Parola included the four species of invasive carp in his recipe book “Can’t Beat’ Em, Eat’ Em.”

In June 2022, the state of Illinois unveiled a rebranding of Asian carp as Copi, which it described as “mild, clean-tasting fish with heart-healthy omega-3s and very low levels of mercury.”

A second issue is that the flesh of Asian carp is quite boney. The USGS’s Chapman has gone so far as to create a series of videos demonstrating how best to filet the fish.

“I eat every grass carp I can get my hands on,” he reported. “Next to walleye, (it’s) my second favorite fish to eat in Missouri.” (For Super Bowl weekend, he reported, “I have a bowl of grass carp ceviche waiting for me”).

Yet another approach is to harvest and sell Asian carp to those who already love them: Asians. At Wickliffe, Kentucky, where the Ohio River meets the Mississippi, Chinese-American entrepreneur Angie Yu’s Two Rivers Fisheries declares itself to being “America’s largest Asian carp processor and exporter,” buying carp from commercial fishermen (or “fishers”) who harvest them in the two big rivers as well as Barkley and Kentucky lakes. It markets them as “wild caught in the USA” (as opposed to fish-farmed) and sells them as fish steaks, ground fish meat, meatballs, patties, salted fish and more.

Two Rivers is one of about a half-dozen buyers of Asian carp in Western Kentucky, paying varying amounts depending on the end use — less for grinding them to fish meal, more for processing them for human consumption.

Bubbles and sound

Other approaches are more specialized.

In 2019, an experimental barrier called a bio-acoustic fish fence (or BAFF) was installed on the downstream side of the lock at Barkley Dam as part of a three-year, $7 million state-federal evaluation to deter Asian carp from migrating from the Cumberland River to Lake Barkley.

The BAFF sends a curtain of bubbles, sound and strobe lights from the riverbed to the water surface, meant to deter Asian carp from entering the lock chamber.

“Silvers and bigheads have a lot more sensitive hearing than native species,” Tompkins said. “To silver carp, they perceive that (curtain of bubbles) as a solid structure.”

“Bubbles, lights and sound. All enemies of the Asian carp,” White said.

“It’s been successful, more successful than some people might have thought,” according to Dave Dreves, director of Kentucky Fish and Wildlife’s Fisheries Division. “The success is not 100% moving across it. No one expected that. The success is being able to deter fish — deterrence rather than a barrier. The whole idea is to deter. Then we can fish the carp numbers (in the lake) way down.”

But the existing BAFF at the Barkley Lock is only under lease and is scheduled to be removed this fall. “It has to be purchased to be in place indefinitely,” and that would cost as much as $5 million, Dreves said. “Everyone wants it to stay but someone has to come up with money. The (U.S. Army) Corps (of Engineers) has money, but it requires 25% non-federal match.”

There’s also interest in installing BAFFs at the locks at Kentucky Dam — the existing lock and a larger lock that’s under construction — which would cost millions more.

The modified unified method

Meanwhile, interest focused on the Chinese “unified method” of using large nets to herd carp for harvesting. The USGS sent biologist Chapman and colleague to China to study such methods; they made adaptations, such as incorporating low-voltage electrical jolts and underwater speakers, that became known as the “modified unified method,” or MUM, to drive the carp into a relatively small takeout point.

“We’ve had extremely good success in floodplain lakes with the MUM (in Creve Coeur in Missouri and in northern Illinois), and the process is now being used commercially to remove silver carp from privately owned lakes that have been invaded by carp during floods,” according to Chapman.

Wade White helped enlist the help of then-U.S. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky and others in the War on Carp. In February 2020, banked by millions of dollars in federal funding, the MUM was brought to Kentucky Lake for a test. McConnell, Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear and other dignitaries, with TV crews and other news media in tow, arrived at Pisgah and Smith bays to see the state-federal multi-agency experiment, with some two miles of nets, in action.

For all the interest and initial excitement, the experiment fell short of hopes. Cleaning out carp from a small lake is one thing; to clear them out of the largest artificial lake east of the Mississippi, at more than 160,000 acres was quite another.

“(In) Kentucky Lake we can't fish the entire water body as a whole, and the fish know there is this big lake out there, to where they can run — so they know where to go to escape, and they use their jumping ability get over the nets, or even their huge abundance to just push nets down and get away. Since we are netting off an entire cove, this means that the line we have to protect is very large, and it's hard to protect the whole thing. So, in all, it didn't work out very well in those situations.”

Disappointed, White wrote to McConnell urging him to direct the U.S. Geological Survey to discontinue the MUM in Kentucky, particularly since its use a second year was aimed more at research than fish removal.

“There’s always room for research, but I like action,” White said. “In the past, a lot of this money has gone to research. You can research to death.”

“The way it was rolled out before was really labor intensive,” Kentucky Fish and Wildife’s Dreves said. “That’s not a direction we are going right now.”

But hope was not lost.

Commercial fishers

For Wade White’s money, nothing beats the efforts of commercial fishermen who have captured literal tons of Asian carp in nets in a single day that they sell to fish markets or fish processing plants.

For their efforts, commercial fishermen are paid cents per pound for Asian carp. Aquatic Protein has paid 8 to 12 cents a pound for carp that will be turned into fish meal, while fish markets buying carp for human consumption have paid between 14 and 20 cents per pound. It’s tough for commercial fishermen to pay crew and operating expenses and realize much of a profit at those prices.

To incentivize the fishers, Kentucky Fish and Wildlife in 2015 initiated a five-cent-per-pound subsidy for Asian carp over eight pounds (double that for smaller carp) harvested from Kentucky Lake and Lake Barkley. The subsidy today is a flat eight cents per pound.

It also installed a commercial ice machine near the Kentucky Dam Marina so commercial fishermen could load hundreds, even thousands of pounds of free ice to keep fish cold during warmer times of the year.

In the first few years of the program, commercial fishermen (27 of them in 2016, dropping to 15 in 2017 but increasing since then) harvested nearly 4 million pounds of Asian carp from the lakes — just over 3.9 million pounds of silver carp and 72,527 pounds of bighead carp.

In 2021, commercial fishers removed a record 9.6 million pounds of Asian carp from Kentucky waters, dipping slightly to 9.5 million pounds in 2022, mostly from Lake Barkley and Kentucky Lake, Kentucky Fish and Wildlife reported.

During the 12-month period ending this June, the state will pay out $800,000 in subsidies “basically for the (two) lakes,” fisheries director Dreves said, and is also paying contract fishers $350,000 for harvesting carp from pools on the Ohio River downstream from Louisville.

Military veteran Danielle Demello has seen both sides of the commercial fishing equation. She managed Aquatic Protein’s buying station at Eddyville until she went into business as a commercial fisherman.

“I went full force,” deploying sets of big gillnets, she said.

“I drop big huge, giant nets,” Demello said.

With help from friends, family members and other commercial fishermen, her gill nets have made some huge hauls of Asian carp. On Jan. 16, 2022, she posted to Facebook photos of a catch of 22,912 pounds.

But not every day is like that. “It depends on the time of year, weather, a billion things, which is why it’s called ‘fishing’ and not ‘catching.’” Demello said. “The worst (day there) were two fish in my net. The best was 29,700 pounds of fish one 23-hour day. Grinding, I mean like, grinding,” pulling nets in by hand with two helpers and dropping carp into the hull of her big Jon boat.

The game changer?

But perhaps no one can out-catch a commercial fisherman named Wade Robbins.

“He’s the best of the best out there,” Demello said.

Robbins uses a new technique he calls trap netting that brings in so many Asian carp that he needs a hydraulic crane to pull up hundreds of pounds of fish at a time.

In November 2021, Wade White posted a short video showing Robbins and his crew at work on Lake Barkley. The crew had located a large school of Asian carp and set out seine netting to encircle the school, then drew in the netting to concentrate the fish in a small confined area.

The video showed Robbins using a hydraulic crane mounted in his big Jon boat to lower a scoop net that’s larger than a household washing machine into the water. Seconds later the crane operator raised the net, full of dozens of wiggling Asian carp, most of them two feet long or greater, that were dumped into plastic gaylord containers.

“Wade Robbins invested a lot of in industrializing his process, using hydraulics and less manpower and 36- to 38-foot (Jon boats with) all-weld quarter inch aluminum hulls,” Tompkins said.

White reported that Robbins and his crew harvested 27,000 pounds of Asian carp in four hours. He said the only other species caught were one redear sunfish and one channel catfish, both of which he said were released unharmed back into the lake.

Unfortunately for Robbins, his netting method was considered experimental — Dreves said state officials were concerned that industrial-scale fishing would remove desirable species like bass and crappie along with the invasive carp — so he wasn’t eligible for the state subsidy. (For a time, Lyon County provided him a 4-cent subsidy paid from funds provided by American Fishing Tackle Co., or AFTCO.)

Over an extended time, Robbins “was vigorously vetted by the department,” Kentucky Fish and Wildlife’s Tompkins said. “We had staff with him anytime he was using seining methods on the rivers or the two reservoirs” and would sample his catch for the presence of desirable native species, or “bycatch.”

“His sportfish bycatch would be really low,” Tompkins said. “Occasionally a channel catfish would get tangled in net. There would be two or three pounds of (native) fish versus 100,000 pounds of silver carp.”

In early February 2023, White reported on the War on Carp Facebook page that Robbins had been approved for the state subsidy.

“Why does this matter?” White wrote in that post. “Because on KY Lake, just in 2 days, he caught 57,000 lbs and today he caught 35,000 lbs. This technique is a game changer and others will learn it. We are going to win the War on Carp.”

“We’re really happy to have him as an asset,” Tompkins said of Robbins.

Fisheries director Dreves said Kentucky Fish and Wildlife anticipates that more commercial fishermen will adopt Robbin’s method through memorandums of understanding with Kentucky Fish and Wildlife this year while proposed changes in regulations are considered. With that in mind, he expects Kentucky’s budget for subsidies to increase to $1 million in the fiscal year that begins July 1.

Encouraging news

On Lake Barkley and Kentucky Lake, there are fewer reports of jumping from the water and landing in boats.

“About a year and half ago, you could really start seeing changed,” White said. “Tourism is back. When you go on the water, they don’t jump in the boat. There’s still a lot of carp, but not so many jump in the boat.”

“It’s been months since one jumped in my boat,” he said. “Three or four years ago, if I’d go out on the lake, unless it was really cold, I would get several in the boat.”

Also, larger specimens of silver carp are less common.

“Silver carp in the Missouri River averaged about 12 pounds in 2003, but now one over 6 pounds is uncommon,” the USGS’ Chapman said.

“In the lower Illinois, there are so many silver carp that they grow very slowly most years and getting one over 5 pounds might be hard some years,” he said.

Fisheries biologist Tompkins said scientific researchers rely on two sources of information: formal biological measurements and surveys of the general public, such as boaters, anglers and the commercial fishing industry.

Surveys of the public “give a lot of indication that they’re seeing fewer (Asian carp) and fewer encounters with those fish jumping in boats,” he said.

Meanwhile, he said preliminary U.S. Geological Survey models indicate the commercial fishing “removal programs in the two western reservoirs are doing what they’re supposed to do and reducing the population” — what biologists call “overfishing,” which would be bad if it were smallmouth bass but is good in the case of an invasive species.

“We’re overfishing, which is our objective,” Tompkins said.

“I’m very optimistic that we’re going to have a good handle on carp numbers in the western reservoirs,” he said. “As long as things hold as they are now, we’ll see a definite decrease in population to point where not as noticeable for general public. That’s mainly driven by the commercial removal.”

Meanwhile, “A lot of fishermen have come back and realized these (sport) fish (such as bass, bluegill and crappie) are back,” White said.

“Commercial fishermen thinned out the carp enough so they’re not eating everything in the water, so the bait fish are back. When you watch the sonar, you can see bait fish all over the place, more than I’ve seen in years. It’s made a tremendous change.”

The Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife has posted schedules for 46 fishing tournaments on Kentucky Lake in 2023 and 25 on Lake Barkley.

“I feel like our lakes are back,” White said. “It’s not where we want them, but they’ve actually improved faster than I thought (they would). That’s not scientific; it’s just people talking about it and people sending me emails and me being out here. I’ve seen it go from good to terrible to good again.”

“There’s definitely that anecdotal information,” Kentucky fisheries director Dreves said. “Commercial fishermen are telling my biologists they work harder to find big schools they’re trying to harvest, but in same breath they’ll tell us, despite the fact they’re working harder to find big schools, they’re being really successful in harvesting carp in even greater numbers. The hope is they’re getting more effective rather than there being more carp around.

“Anglers are telling us they’re doing better, they’re catching more fish, they don’t think the carp as prominent as they were,” he said. “We do have that good anecdotal evidence working for us.”

And while the Asian carp harvest was down slightly last year, Dreves believes that more commercial fishers who secure permission to use methods such as Wade Robbins could bring those numbers back up.

The next chapter

Meanwhile, White last year didn’t seek re-election as county judge/executive in Lyon County. President Joe Biden last year nominated him to serve on the board of directors of the Tennessee Valley Authority. A White House news release cited his launching of the War on Carp as among his accomplishments and contributions to the Tennessee Valley. (White also now works for a Western Kentucky bank in business development and public relations.)

In late January came the announcement that the management of his War on Carp Facebook and web campaign would transfer to Wildlife Forever, a 35-year-old nonprofit conservation organization that, with support from AFTCO (which donates $5 to the War on Carp for each carp T-shirt it sells), intends to expand the educational campaign nationally.

“Wade’s visionary efforts inspired federal legislation that resulted in millions of dollars for carp removal and mitigation projects,” Wildlife Forever President & CEO Pat Conzemius said in a statement.

Commercial interests, such as Yamaha (which manufactures outboard motors popular with many boaters and fishermen) and the American Fishing Tackle Co. (AFTCO), are investing in campaigns to raise awareness of the threat posed by Asian carp and the need to seek means to control them,

Meanwhile, Chapman, the USGS fish biologist, is semi-retired but remains cautiously hopeful about controlling Asian carp.

“We probably are not going to really solve the bigheaded carp problem only by catching the adults,” he said.

Other methods that have been proposed from identifying a poison that affects only one or more of the Asian carp species to finding a way to sterilize the invaders or their offspring.

What’s next?

Twenty years ago, practically no research was available on Asian carp in the wild in U.S. waters, “so we were babes in the woods,” Chapman said.

“There has been intensive research on these fish beginning about 20 years ago, and we know SO much more about these fish now than we did then, and now they are among the best-understood species in the world. We can use that knowledge to manage these fish,” he said. “These are amazing fishes, but they are not magical.”

On the other hand, Chapman said, “When you know almost nothing, knowledge growth can be explosive, but now we are reaching the point where the low hanging fruit has been picked, and it takes very hard work that takes a long time to move further.”

“I definitely don’t think there’s a silver bullet coming in the near future,” state fisheries director Dreves said. “With additional research, I think we’ll find better and better ways to control these things …

“Often you don’t get rid of invasive species,” he said. “I’m optimistic we’ll just learn to manage them better.”

This article originally appeared on Evansville Courier & Press: Yearslong war on Asian carp showing some progress, but end is uncertain

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos