Car Companies Have a New (Old) Revenue Stream: Multi-Million Dollar Customs for the Ultra-Rich

When Aston Martin's Q division unveiled its one-off coachbuilt Victor supercar at England’s Hampton Court Concours of Elegance in the fall of 2020, the internet released a collective tongue lolling worthy of a bawdy cartoon wolf.

This story originally appeared in Volume 12 of Road & Track.

SIGN UP FOR THE TRACK CLUB BY R&T FOR MORE EXCLUSIVE STORIES

Built using the leftover engine and monocoque from a prototype of the marque’s limited-edition One-77 supercoupe, this gorgeous menace featured an uprated version of that car’s howling naturally aspirated V-12—now making 848 hp—and a proper six-speed manual transmission instead of a six-speed paddle-shift automatic. It also hosted custom carbon-fiber bodywork that paid homage to the venerable British brand’s Seventies oeuvre, specifically the DBS V8–based race car nicknamed “The Muncher.” On the cusp of Gaydon’s move into the ultraluxury mainstream with the DBX SUV, the One-77, retro but not slavishly so, felt like an exquisite tribute to the brand’s oft-maligned Malaise Era heritage, a callback to when Aston was weird.

But the nod went deeper, all the way back to the company’s founding in 1913 by Robert Bamford and Lionel Martin. “These two guys effectively personalized and coachbuilt cars that already existed,” says Marek Reichman, the brand’s executive vice president and chief creative officer. “They took Singers, they took other chassis, and made them lighter. And later they improved the horsepower of the car. They put a different body on. Why? To make it faster. So they took something that existed, they put their ingenuity into it, and they changed it.”

This aligned with ultraluxury automotive trends at the time. As Reichman says, “You would get a chassis from Rolls-Royce, Bentley, Bugatti, and you went to Mulliner, or you went to Park Ward, or you went to Figoni et Falaschi, and you had a body put on this existing chassis. You personalized the body with your coachbuilder,” a business that often had roots in the horse-carriage trade or craft.

This practice of having a car custom-built to personal taste mostly disappeared from the ultraluxury market in the mid-20th century. But it has made a stunning return in recent years. Seven- and eight-figure vehicles with extremely limited production runs—from one or a few to several hundred—and infinite potential for individualization have become fixtures on the show-car circuit, their names frequently harking back to a famed forebear: Daytona, Countach, Voiture Noire.

But why is this happening now? And where is it going? To start, we must go backward to an understanding of what standardization has wreaked in luxury.

“In the automotive context today, cars are these industrially manufactured pieces of design that share a common shape and a common form, and we’ve come to know that individualization and personalization work off this known canvas,” says Alex Innes, Rolls-Royce’s head of coachbuild design, responsible for the two stunning Rolls Boat Tail commissions revealed at the Concorso d’Eleganza Villa d’Este this year and last. “In the Twenties and Thirties, that was the other way around. Because they were not hindered by any predetermined notion of repeatability—making more cars—there was a level of self-expression and individualization that is quite honestly still a guiding inspiration to us.”

This absolute sense of personalization gave Rolls-Royce, Duesenberg, and Isotta Fraschini a distinct position within the era’s automotive pantheon, one that existed to shower grace and ego, not upon the car but upon the customer. “If you think about a sports-car brand, the history that is revered with those cars is about the accomplishment of the car—its performance, its participation in certain races,” Innes says. “But if you look at the history of the most significant Rolls-Royces, you often talk about its client, their successes, their accomplishments, and the fact that they celebrated that success through commissioning a unique Rolls-Royce. It is about legacy, about dynasty.”

This refracted glory holds great allure for contemporary luxury brands. “The ultimate expression of luxury is to have one of one,” says Brandon Vivian, executive chief engineer for Cadillac. The onetime “Standard of the World” brand is attempting to revive coachbuilding with its forthcoming Celestiq flagship electric sedan, a $200,000-plus model it compares to the Rolls-Royce Ghost in prestige. Still, Cadillac is quick to remind doubters that it never left the practice, having long constructed ambulances, hearses, and livery vehicles—including the ultimate coachbuild, the presidential limousine.

The glorification of individualization isn’t just about the good fortune of garnering something conditioned by resolutely enforced scarcity—though, of course, it is about that. It also gives a client a sense of deeper participation in and connection with a beloved brand, a type of access reserved only for the best, and highest-spending, clients. Rolls-Royce even has a name for such customers: Luminaries.

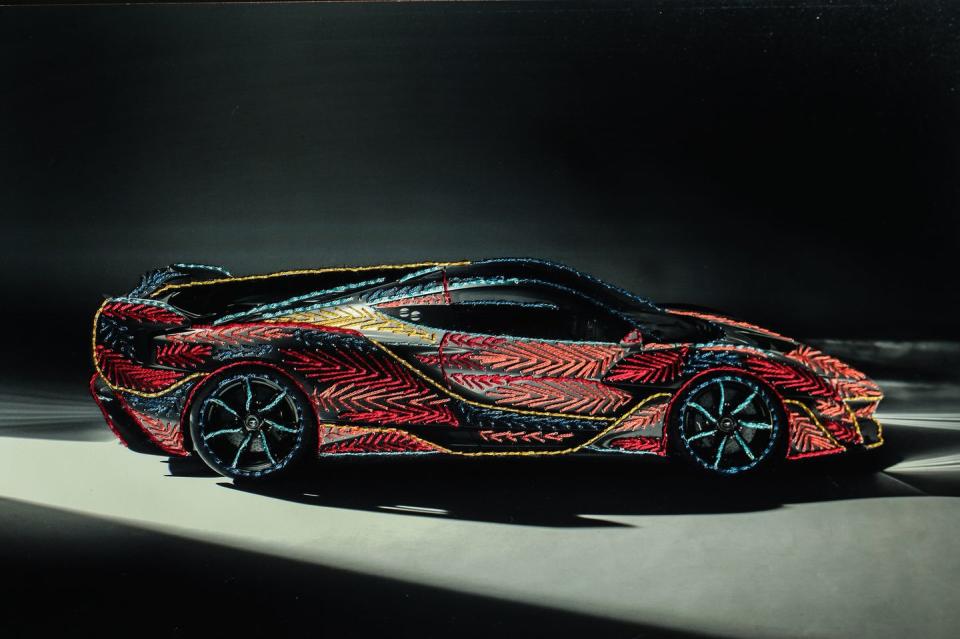

Spec’ing, developing, and aiding in the design of a limited-edition or coachbuilt car provides such buyers with extraordinary entrée: to executives, to designers and the design studio, to the behind-the-scenes workings of the company. It’s just this kind of experience that these consumers crave. “They want to understand the journey, as well as be part of it,” says Ansar Ali, managing director of McLaren Special Operations, which oversees the marque’s customized and extremely limited vehicles, like the recent $3.9 million Sabre. “When they meet a particular person and have a particular conversation, it becomes almost a stake in the ground that they can refer to later when they take ownership of the car. Having this personal story, for our clients, is just as important as the end product in many ways.”

Moreover, the customer-funded R&D involved in these projects—be they advances in aerodynamics, lighting treatments, trim materials, or additive manufacturing techniques—creates an idealized halo for the brand and filters down into its broader offerings. “Celestiq signifies a new resurgence for Cadillac itself,” Vivian says, “so the learnings derived there are going to be shared across the Cadillac portfolio.”

Intriguingly, the imminent global shift toward electric vehicles has factored into the coachbuilding resurgence, albeit counterintuitively. “There’s an awareness of that break,” says Ali. “And there are a few clients who are talking to us, and I’m sure some other brands, trying to get in their last internal-combustion-engine car before they’re eliminated.”

But as in previous eras of extreme income inequality, the real driver is the immense fortunes of the wealthy. They have continued to surge even through the pandemic, the vagaries of which have motivated billionaires to splurge rather than defer joy.

“In the past 18 months, there’s been a huge increase in demand for high-end luxury vehicles,” says Michael Dean, a luxury-automotive equity research analyst with Bloomberg. “If you look at Rolls-Royce, Bentley, Lamborghini, Ferrari, all their ‘normal’ vehicles are sold out for 12 to 18 months. Their special vehicles, which they make huge margins on, are also snapped up as soon as they come out. So an extension of that is doing more one-offs. If you can charge more money for it, and enough high-net-worth individuals are there to bite your hand off to buy them, then it’s very, very profitable.”

How profitable? “Profit margins on some of this stuff is like 70 or 80 percent,” Dean says. “If you can charge millions for these cars, and they’re quite often based on current six-figure production platforms, then it’s very lucrative.”

So lucrative, they can have a significant impact on a company’s bottom line. “Aston Martin has the Valkyrie, at $3 million each, and they’re going to make 90 in 2022. I’d say that’s something like 30 percent of their entire revenue for this year,” Dean estimates. (This practice is not new at Aston. According to Reichman, one-off commissions for wealthy collectors, like the Sultan of Brunei, helped provide sustaining “profitability during the fallow period in the Eighties.”)

Dean also singles out the world’s most profitable carmaker: “One of the reasons why Ferrari’s margins are going to go down for the rest of the year is the Monza production and sales are finished and the Daytona won’t start until 2023. The additional profitability from those cars could add $50 million to the earnings.”

Of course, such vehicles are also a decent deal for the elite few who can afford them. “If you’re lucky enough to get one of these cars, they often sell for 50 to 100 percent more than list price on the secondary market,” Dean says.

While the industry’s ongoing conversion to electric power is catalyzing the current gold rush in custom peak internal combustion, it’s unclear how this shift will affect the future of coachbuilding. There is a sense that the skateboard-plus-top-hat construction typical to contemporary EVs—wherein the battery and drive components are housed down low and capped with whatever body type—may offer some liberation from design and production conventions. “With electrification, you are more free from some of the hard points you currently have,” Reichman says, referring to the predetermined location of components like engines, transmissions, exhaust systems, and fuel tanks. “It can allow greater flexibility for sure, because you’re relatively constrained with internal combustion.”

Other technologies may further enhance this freedom. “I can 3D-print,” Reichman says. “Maybe I don’t have to manufacture at the factory. Maybe I can print a body on location and can come to your home and build your car for you.”

Of course, anything like this would require a shift in legislation. “I think the regulatory requirements and environments are a much more difficult set of equations to solve than whether you have an internal-combustion or electric powertrain,” Vivian says. And no one knows for sure how that will work out.

Ali says McLaren is not yet in conversation with anyone to do an electric coachbuild. But when such commissions do eventually come, the automakers’ special coachbuilding divisions will be ready, as they are for any other entreaty from their most beloved customers. “Quite simply, we’ve never had to say no to a client request,” Innes says. He claims this is because Rolls-Royce Luminaries tend to self-select among the steadily marque-adherent: “We don’t lead people into the design studio if we don’t believe in the values they represent or their appreciation of the brand.”

Yet even these clients still occasionally require a bit of stern guidance. “If you’ve got a toothache, you go to the dentist,” Reichman says. “However much you believe you could pull your own teeth, you can’t. So, you can come in with ideas, but ultimately, we will steer you in the direction that you will fall in love with.”

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos