What If the Whole Car Were a Gas Tank?

Twenty dollars. That’s what a 315-gallon auxiliary fuel “belly tank” for a World War II P-38 Lightning fighter plane cost in the late Forties at a military-surplus store in California. Alex Xydias, founder of So-Cal Speed Shop, bought one of the streamlined tanks back then, but cautions: “It’s not as cheap as it sounds now. You could buy a whole car for $50 back then. But I would have paid anything for it.” Xydias was going racing on the dry lakes northeast of Los Angeles. He had a chassis built using Ford Model T bits to go under his aluminum teardrop, and he mounted a Ford flathead V-8-60 in the tank’s tapered tail. The So-Cal belly tanker wasn’t the first, but its success on the dry lakes and later at Bonneville (where it hit 198 mph in 1952) has made it the archetypal example. Like most race cars, it was a constant work in progress. Over the years, it was fitted with different engines, wore a different streamliner body, and then was rebuilt with a custom chassis from underneath. Some 40 years after the belly tanker’s racing career ended, collector Bruce Meyer found it, or its pieces anyway, and had it restored. “I couldn’t understand why Bruce was so happy to find all those old, rusted parts,” Xydias says. He’s happy now too.

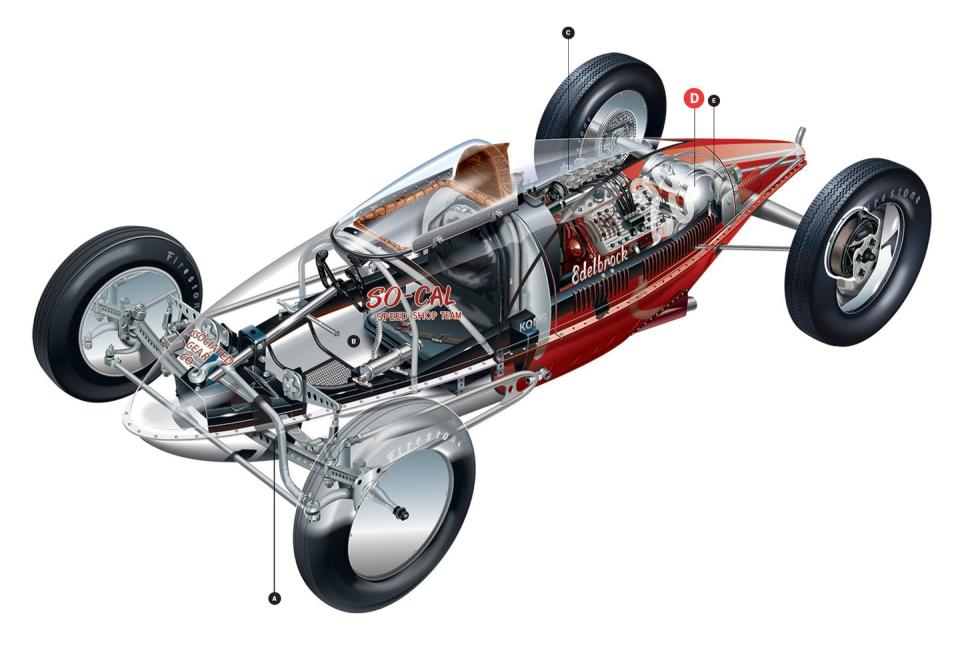

A.

In its final form, the belly tanker used a Ford Model A front suspension with a transverse leaf spring and archaic Hartford friction shocks. Then So-Cal builder Dave DeLangton drilled speed holes in every bit he could and had all the pieces cadmium coated. Chrome would have been a little showy for a race car.

B.

The accelerator pedal is about the only carlike control in the belly tanker. The steering yoke is the same one used in a Douglas A-26 bomber. The brakes are activated by the vertical lever to the left of the yoke. The clutch is operated by the horizontal lever to the right. And there’s a hand pump to the driver’s left for the pressurized fuel system.

C.

The tight engine bay saw a variety of flathead engines over the years (three in the 1952 Bonneville Nationals alone). It’s currently fitted with an AB block with a row of four Stromberg 97 carburetors. Note that the rear two carbs have had their throats cut at an angle so they fit under the tapered body. The tank between the driver and the engine is for coolant. The vehicle has no radiator or fan.

D.

Mounted atop the rear end is a small fuel tank (that’s right, a fuel tank inside a fuel tank). By the end of the belly tanker’s racing career, Xydias was mixing nitromethane into the gasoline for extra power. At Bonneville in 1952, Xydias found himself in a pitched battle against another belly tanker powered by a then-new Chrysler Hemi. He pushed the nitro mix to 40 percent, but the engine couldn’t take it, and he “tuliped a valve.” That was the end of that.

E.

A Ford transmission with only its high gear sends power to a Halibrand quick-change rear end in the center of a solidly mounted Ford axle housing. So, the belly tanker did not accelerate quickly or tolerate bumps, but it at least had very little braking power. The rear drum brakes are from a late-Forties Ford road car. And the front brakes, well, there are no front brakes.

A car-lover’s community for ultimate access & unrivaled experiences.JOIN NOW Hearst Owned

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos